Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (14 page)

On 7 November 1857, after weeks spent crossing Ugogo’s dusty, lifeless winter jungle, Burton and Speke entered the Arab trading settlement of Kazeh (Tabora) with their caravan to the sound of ‘booming horns and muskets ringing like saluting mortars’. They had marched about 600 miles in 134 days. A welcoming party of half-a-dozen white-robed Arabs led them to a pleasant

tembe

(a house with a veranda and inner courtyard) which was placed at their disposal for the duration of their stay.

The two men had a letter of introduction to a leading Indian trader, Musa Mzuri, but in his absence his Arab agent, Snay

bin Amir, who was a rich ivory and slave dealer in his own right, overwhelmed Burton with gifts of goats, bullocks, coffee, tamarind cakes and other delicacies. ‘Striking indeed,’ wrote Burton, ‘was the contrast between the open-handed hospitality and the hearty good-will of this truly noble race, and the niggardliness of the savage and selfish African – it was heart of flesh after heart of stone.’

43

Snay from now on would spend every evening conversing in Arabic with Burton, who described his host as well-read, with ‘a wonderful memory, fine perceptions and [being] the stuff of which friends are made … as honest as he was honourable’. In fact he was a slave trader – an occupation anything but honourable. When David Livingstone accepted help from such men, he did so from necessity, with deep regret, because he loved Africans and knew he had to survive in order to expose their exploiters, whereas Burton despised Africans and the anti-slavery humanitarians who espoused their cause.

44

A few years later, Burton still thought of the Kazeh Arabs as his friends, and denounced Speke as heartless, because, during his next expedition, he refused to assist Snay bin Amir against Manwa Sera, the African king of the Nyamwezi. But Speke preferred Manwa Sera as a man, and thought him perfectly entitled, as the local African ruler, to levy a tax on Snay and his fellow traders.

45

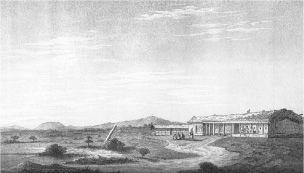

Kazeh.

Snay had visited ‘the great Lake Tanganyika and the northern kingdoms of Karagwah and Uganda’. Because Speke could not understand Arabic, he found himself excluded from fascinating information until he began to feed questions for Snay to Bombay in Hindustani, for him to repeat to the Arab in Kiswahili before translating his replies back into Hindustani for his master.

46

While Burton was confined to his

tembe

with fever, Speke – with Bombay interpreting – learned from the Arabs that there were three lakes and not the single immense slug shown on the German missionaries’ map. To the south was Nyasa (Lake Malawi), to the west the Ujiji lake (Lake Tanganyika), and to the north ‘the sea of Ukerewe’ (Lake Victoria), which might be largest of all. From the Ukerewe lake’s position, due south of the White Nile, Speke reckoned it was more likely to be the source of the Nile than was the Ujiji lake, which the RGS’s instructions had named as their objective.

47

But, though the Ukerewe ‘sea’ was slightly closer than the Ujiji lake, Snay warned them that the journey to it would be too dangerous to attempt.

While they were at Kazeh, Burton became gravely ill and Speke feared he would die if they did not leave at once for a healthier place. Burton wanted to stay on with Snay but on 5 December he had to admit he was ‘more dead than alive’ and ought to go.

48

Shortly before they left, when Burton seemed very briefly to be a little stronger, the pair discussed Snay’s geographical information, with Speke in favour of visiting the northern lake, despite the added danger. Burton overruled him. ‘Captain Burton preferred going west,’ Speke wrote curtly in his journal. And because Burton was still rational, although unable to walk, as commander of the expedition he had to be obeyed.

49

Shortly after the sorry decision to head west had been made, Speke persuaded Burton ‘to allow [him] to assume the command

pro tem’

so he could organise their removal from Kazeh.

50

By the time Speke had recruited fresh porters and collected up additional loads of cloth, beads and brass wire, Burton’s health had taken another turn for the worse. Indeed, when Speke led the expedition into the next staging post

en route

to Ujiji, Burton

had to be lifted from his

machilla

(litter) and ‘begged Speke to take account of his effects, as he thought he would die’.

51

On 18 January 1858, Burton’s ‘extremities began to burn as if exposed to a glowing fire’ and he sensed death approaching. Later he recalled the horror of it:

The whole body was palsied, powerless, motionless, and the limbs appeared to wither and die; the feet had lost all sensation, except a throbbing and tingling, as if pricked by a number of needle points; the arms refused to be directed by will, and to the hands the touch of cloth and stones was the same.

Burton would not be able to move his limbs for ten days, and it would be eleven months before he would walk unassisted. Until then he had to be carried by six slaves – eight when the path was difficult.

52

Lake Tanganyika was 200 miles distant, which seemed certain to be a gruelling ordeal for him, even on a litter.

At last on 13 February, after fording three small rivers, the caravan struggled through several miles of tall grass and then climbed a stony hill. As they reached the summit, Speke’s ailing donkey died under him. For two weeks he had been suffering from ophthalmia with both eyes inflamed and sore and his vision so seriously impaired that he needed to be led when riding. Just behind him, Burton’s sweating carriers arrived at the top of the hill supporting their master in his

machilla.

On catching sight of a streak of light far below, Burton asked Bombay what this was. He replied unemotionally: ‘I am of opinion that that is the water.’ After being carried a few yards more, Burton gained his first uninterrupted view of Lake Tanganyika. Fringed by ‘a ribbon of glistening yellow sand [lay] an expanse of the lightest, softest blue, in breadth varying from thirty to thirty-five miles and sprinkled by the crisp east wind with tiny crescents of snowy foam’. Beyond the lake were ‘steel-coloured mountains capped with pearly mist’.

53

In his state of near blindness, Speke was devastated that ‘the lovely Tanganyika Lake could be seen in all its glory by everybody but myself’.

Arriving at Ujiji, the lakeside Arab slave-trading settlement, the explorers were told that the lake measured 300 miles from

north to south – in fact it is just over 400, making it the world’s longest. Burton’s guess that it was about thirty-five miles across at its widest point was a slight underestimate.

Although they were the first Europeans to have reached any of Africa’s great lakes, and had done so despite repeated attacks of fever, partial blindness, and in Burton’s case paralysis of his legs, both men knew that a lot more had to be done to confer greatness on their journey. After all, an unspecified number of Arab and Nyamwezi slave and ivory traders had preceded them to the lake, none of whom had thought it sensible to tell people about it, or worthwhile to explore it thoroughly. Burton’s RGS instructions had required him and Speke to reach Lake Tanganyika and then ‘to proceed northwards’ to find out whether it might in some way be linked with the White Nile and the Mountains of the Moon. If they could make decisive progress in this direction, their journey might yet be acclaimed as one of the greatest ever made on land. While they had been at Ujiji, several informants had electrified them with the news that ‘from the northern extremity of the Tanganyika Lake issued a large river flowing northwards’.

54

No Arab they had spoken to had actually seen this river himself, and local Africans claimed to be ignorant of it. So visiting this river in person was of the utmost importance. This was particularly true for Burton, who had chosen to come to this lake rather than to the larger ‘Sea of Ukerewe’ which Speke had been in favour of exploring first.

The height of Lake Tanganyika above sea level was 1,850 feet, according to the more dependable of the expedition’s two bath thermometers. (Their three specialist boiling point thermometers had all been inadvertently damaged.) Although the true height is 2,600 feet, even that level (had Burton known it) would not have reassured him. Since there were many known cataracts on the Nile – and others still to be discovered – the higher the lake, the greater the likelihood of its having some connection with the Nile. In this connection, it must have troubled Burton to know (as he did) that Kazeh, which was due south of the Ukerewe lake, was 4,000 feet above sea level, making it seem likely that

the larger lake, which he had chosen not to visit, was going to be considerably higher above sea level than Lake Tanganyika. Yet Burton preferred to ignore this unwelcome probability.

55

In truth, on his arrival at Ujiji, Burton was too ill to write or even talk, and lay prostrate on the earth floor of a hut for a fortnight, unable to move his legs. He was also suffering from ophthalmia – although not as badly as Speke. Despite his brief period in command, Speke was not prepared to make the next crucial decisions and waited for Burton to recover sufficiently for them to be able to discuss their next moves. Each day at noon, ‘protected by an umbrella, and fortified with stained-glass spectacles’, Speke visited Ujiji’s market. Here he purchased daily supplies for the porters and other servants. Displayed for sale were fish, meat, tobacco, palm oil, artichokes, bananas, melons, sugar-cane and pulses. On certain days, slaves and ivory could also be bought.

56

When Burton felt slightly stronger, he told Speke that they would have to hire from Hamid bin Sulayyan, an Arab slave trader, the only sailing dhow currently on the lake. Hamid lived on the far side of Tanganyika, so somebody was going to have cross in a dugout. Burton dithered because he thought this too dangerous for Speke. Nor did he trust Kannena, chief of the people living in and around Ujiji. ‘Seeing scanty chance of success, and every prospect of an accident,’ Burton decided to send his

factotum,

Said bin Salim, whose life he felt easy about risking. When the Arab flatly refused to undertake the mission, Speke offered to go in his place. But Burton, who still felt ill enough to die, did not want to risk leaving the expedition leaderless should Speke also perish. With slave traders active on Tanganyika’s shores, all strangers were mistrusted by local Africans, especially those asking inexplicable questions about rivers. So it was brave of Speke to insist on going.

57

On 3 March 1858, Speke embarked in a substantial dugout accompanied by Bombay to interpret, Gaetano to cook, two Baluchis to defend him, and eighteen local tribesmen to paddle. It was a puzzle how to pack everyone into so small a space along

with their food and possessions. Almost immediately after they left harbour, storms forced them for three days to creep along the lake’s eastern shore. ‘These little cranky boats can stand no sea at all,’ lamented Speke. On one occasion, when they were camped on land, the appearance of a single man with a bow led the whole party to panic and launch the boat at breakneck speed, so great was the crew’s fear of being attacked. Crocodiles also inspired terror, since they were known to clamber aboard dugouts when hungry. Although Burton wrote that Speke never drank or smoked, in fact he smoked a pipe and found it soothing even in the cramped circumstances of a dugout.

58

In the early hours of the morning of the 8th they crossed the lake and during the passage the crew refused to answer Speke when he asked the names of various headlands and bays. They feared that his unnatural inquisitiveness might lead to disaster. In fact the crossing was uneventful, and the locals welcomed them when they reached Kivira Island, a few miles from Tanganyika’s western shore. When harm came to Speke, it was from an entirely unexpected quarter. After a quiet day spent smoking and story-telling with the islanders, Speke lay down to sleep in his tent. A storm blew up, waking him with its powerful gusts, and then subsiding. He lit a candle so he could see to rearrange his kit, ‘and in a moment, as if by magic, the whole interior became covered by a host of small black beetles’. After failing to brush them off his clothes and bedding, he blew out the candle that had attracted them, and lay down. Although insects crawled up his sleeves, down his back and legs and into his hair, he managed to fall asleep, until woken, as he recalled:

[By] one of these horrid little insects … struggling up the narrow channel [of the ear], until he got arrested by want of passage room. This impediment evidently enraged him, for he began with exceeding vigour, like a rabbit at a hole, to dig violently away at my tympanum … I felt inclined to act as our donkeys once did, when beset by a swarm of bees … trying to knock them off by treading on their own heads, or by rushing under bushes … What to do I knew not. Neither tobacco, salt, nor oil could be found: I therefore tried melted butter; that failing, I applied the point of a penknife to his back, which did more harm than

good; for though a few thrusts quieted him, the point also wounded my ear so badly, that inflammation set in, severe suppuration took place, and all the facial glands extending from that point down to the point of the shoulder became contorted … It was the most painful thing I ever remember to have endured … I could not masticate for several days and had to feed on broth alone.

59