Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (11 page)

Burton, as the more experienced and celebrated traveller, wanted a colleague who would always do as he was asked and never challenge him. On their Somaliland trip, he had been struck by Speke’s ‘peculiarly quiet and modest aspect’ and by his ‘almost childlike simplicity of manner’. Only later would he detect beneath Speke’s unassuming exterior ‘an immense and abnormal fund of self-esteem, so carefully concealed, however, that none but his intimates suspected its existence’.

24

Speke would locate the abnormality elsewhere. As he confided to Norton Shaw several years later: ‘He used to snub me so unpleasantly when talking about anything that I often kept my own counsel – Burton is one of those men who never can be wrong and will never acknowledge an error.’

25

Burton from the start recognised Jack Speke as a risk-taker like himself – someone who instead of going home on furlough had travelled alone to Tibet to shoot bears. Risk had drawn Speke to Somaliland, which he knew to be dangerous, as was his desire to shoot Ethiopian elephants. The two men had seemed to have an identical desire to flee the monotony of everyday life.

In October 1856, soon after Speke’s acceptance of Burton’s invitation, an event took place which changed his hitherto temperate view of his leader. In Somaliland Burton had taken charge of his companion’s journal as expedition property, and now, at last, Speke was able to see what he had done with it. Burton’s book about the Somali Expedition:

First Footsteps in East Africa: or, An Exploration of Harar

was published just as the two men were making their final preparations for departure. It contained a thirty-seven-page appendix, insultingly entitled ‘Diary and Observations made by Lieutenant Speke, when attempting to reach the Wady Nogal’. Adding insult to injury, Burton commented that though Speke had been ‘delayed and persecuted by his “protector”

[abban],

and threatened with war, danger, and destruction, his life was never in danger’.

26

Even worse, Burton had printed for public consumption (with one

minor change) the words of his warning that had upset Speke so much at the time of the Berbera attack: ‘Don’t step back or they will think we are retiring.’

27

The whole diary had been heavily cut, and then re-jigged in the third person, but kept in diary form, strongly suggesting that Speke was so illiterate that his work had needed to be completely re-written – an insinuation that would eventually be disproved by Speke’s extremely readable books. Burton’s overlong and invariably overwritten

oeuvres

-although containing many excellent passages – are very hard to get through in their entirety. Speke did not find writing easy, but, unlike Burton, he did at least achieve – with the help of his editors – a fluent and gripping narrative style by writing exactly as he spoke.

28

Though enraged by

First Footsteps in East Africa,

Speke concealed his hurt feelings. Nor did he for a moment consider resigning from an expedition which promised to make them both famous. Even when his anger was fanned by a review of

First Footsteps

– forwarded to them

en route

for Africa – Speke still did not tell Burton what he was thinking. Laurence Oliphant, a writer and traveller who was a member of the RGS Expeditions’ Committee and an acquaintance of both men, had reviewed Burton’s book in

Blackwood’s Magazine,

and had focussed on the author’s cavalier treatment of diaries, written by ‘so able an explorer as Mr Speke’. The able explorer’s observations, wrote Oliphant, deserved ‘to have been chronicled at greater length and thrown into a form which would have rendered them more interesting to the general reader’.

29

Speke was not a conceited man, but he had a strong sense of his own dignity, and this had been injured by Burton’s condescension. He never understood that Burton’s frequent lurches from sincerity into cynicism and back again in his books, and in his conversation, were symptoms of an insecure need to assume an attitude rather than risk ridicule by speaking sincerely. A friend declared that Burton enjoyed ‘dressing himself, so to speak, in wolf’s clothing, in order to give an idea that he was worse than he really was’.

30

It would never have occurred to

Speke that there could be any point in acquiring a reputation for wildness and eccentricity, as a substitute for more reputable achievements. When the pair reached Zanzibar, Speke wrote a letter to his mother, only a fragment of which survives. It includes the sentence: ‘Wishing I could find something more amusing to communicate than such rot about a rotten person.’ He then told his mother that he doubted whether Burton had actually been to Mecca or Harar.

31

While steaming across the Indian Ocean towards Zanzibar, Burton did not tell Speke that he had become engaged to be married before leaving England. The girl’s parents were unlikely to give their consent and the engagement therefore had to remain secret. But if Speke

had

known about this romantic event, he might have looked upon Burton with a little more sympathy. In truth, the self-created ‘Ruffian Dick’ had felt isolated, even vulnerable on the brink of a journey from which he might never return. His mother was dead; his brother had returned to Ceylon; and his sister was preoccupied with her children and her husband. The parents of the two women he had loved – one of whom had been a cousin – had rejected him as a man without money or prospects. Nor had his failure in Somaliland helped his self-esteem, so despite the critical success of his account of his journey to Mecca, he knew that his entire future hinged on the outcome of his new African venture. So it was a blessing that at this time of high anxiety, his personal life offered new hope.

In 1850, he had met nineteen-year-old Isabel Arundell, who had promptly fallen in love with him. She was not strikingly beautiful, had no fortune and her membership of an aristocratic Catholic family seemed unlikely to help his career. But after they chanced to meet again in August 1856, they contrived further meetings and in early October Burton proposed. Before leaving for Africa, he gave her a poem he had written, entitled ‘Fame’, which told the infatuated Isabel more about Burton’s ambitions as an explorer than about his love for her. Indeed there is no evidence that he had fallen in love. He would be far from chaste in the months to come.

32

But there was no doubt that

he

had

never been loved so much before. Here at last was someone who would care whether he lived or died, and if it was to be the latter would venerate his memory – a comforting thought to take to Africa.

So in Zanzibar, where the duo arrived on 2 December, neither man had the measure of the other. Burton had no idea that his companion was still brooding over

First Footsteps,

and Speke had no clue that Burton was a man with strong emotional needs and self-doubts. Yet they were embarking on a dangerous venture which friendship and understanding would have made far easier to endure.

FIVE

Everything Was to be Risked for This Prize

Sighting the African coast from the sea, Jack Speke, who rarely enthused about scenery, was mesmerised by the white coral sands, vivid blueness of the ocean, ‘and green aquatic mangrove growing out into the tidal waves’.

1

Soon the minarets of Zanzibar’s mosques pierced the skyline above the barrack-like Sultan’s palace and the grey-stone consulates. Next, a spidery tangle of ships’ masts and rigging came into view as the breeze wafted seaward the scent of cloves, mixed less pleasingly with the odour of tar, hides, copra and rotting molluscs. A corpse floated near the foreshore which Burton remarked did not discourage ‘the younger blacks of both sexes from swimming and disporting themselves in an absence of costume which would startle even Margate’. He was soon delighted to find that prostitutes were easily procurable in Stone Town.

2

A hundred thousand people -Arabs,

banians,

slaves, freemen, dark-skinned Swahili-speaking Afro-Arabs, and a few hundred consular and trading Europeans – were crammed onto the island.

The two men had arrived on 20 December at the start of what Speke matter-of-factly described as ‘the very worst season of the year for commencing a long inland journey’. At present, the interior was tinder dry, but within weeks the rains would arrive, inundating tracks and paths, and turning vast tracts of country into a quagmire.

3

So they decided to wait several months before setting out for the ‘slug-shaped’ lake. This gave them time to seek out Johann Rebmann at his mission near Mombasa, in the hope of persuading the discoverer of Mount Kilimanjaro to join their expedition. But he found Burton ‘facetious’ and also suspected that he would use unjustified force against Africans during the march to the lake.

4

But though declining to accompany the young travellers, he

did

influence Burton in one crucial way: by dissuading him from travelling inland from Mombasa on the direct route through Masailand. The old Burton would have tried to ‘walk round the Masai’ on the shorter route to the Lake Regions, as Speke claimed

he

would have preferred to do. But the shock of events at Berbera had changed ‘Ruffian Dick’ forever.

5

This was a great pity, since, if Rebmann’s warnings about the Masai had been ignored, Speke and Burton would very likely have shared the expedition’s greatest discovery at an early stage and would never have embarked upon their disastrous feud.

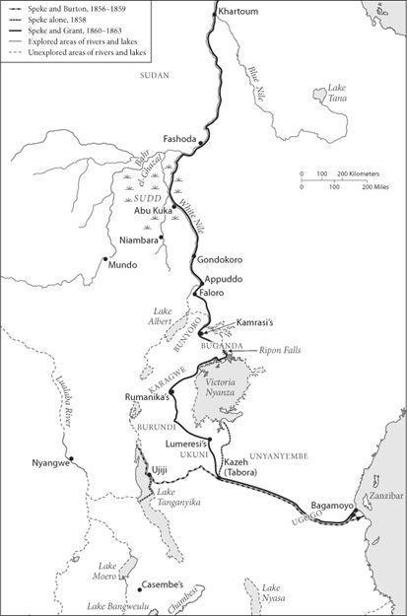

Journeys of Burton and Speke, and of Speke and Grant

Back on Zanzibar the poor health of the British Consul, Lieutenant-Colonel Atkins Hamerton, gave notice of what African fever could do to a man over the years. Though dying, Hamerton hoped to shock the would-be explorers into going back to India while they still could. So he took them to the local prison to make the acquaintance of one hapless convict, chained so tightly to a gun that he could not stand up or lie down. This man’s crime was to have beaten a drum, while Lieutenant Maizan (the young French traveller) had been tortured, mutilated and then beheaded in a macabre ceremony.

6

Though shocked, Speke and Burton knew there could be no turning back

A notable difference between the pair became apparent while they were still on Zanzibar. Everywhere they went slaves of both sexes and all ages could be seen in streets and alleys. Burton guessed there were 25,000 of them on the island – some owned by locals, some in transit to the Gulf, and others for sale.

7

Speke was the more shocked of the two by what he saw at the slave market:

The saddest sight was the way in which some licentious-looking men began a cool, deliberate inspection of a certain divorced culprit who had been sent back to the market for inconstancy to her husband. She had learnt a sense of decency during her conjugal life, and the blushes on her face now clearly showed how her heart was mortified at this unseemly exposure, made worse because she could not help it.

8

By contrast, Burton gazed with detachment at the ‘lines of negroes [as they] stood like beasts’, later describing what he called

‘hideous black faces some of which appeared hardly human’.

9

Burton took pride in refusing, as he put it, ‘to adorn this subject with many a flower of description; the atrocities of the capture, the brutalities of the purchase’. He was convinced that Britain, through a treaty agreed in 1845 with Seyyid Said, the former Sultan of Zanzibar, was making the lives of slaves worse by using the Royal Navy – ‘the sentimental squadron’, as he called the Indian Ocean Anti-Slavery Flotilla – to stop their export. The price of a slave was ten times higher in Oman than in East Africa, and, as Burton pointed out, the more valuable a human chattel was, the better he or she was cared for. So any policy stopping the export trade, and thus keeping more slaves in Africa, lowered their price, and so harmed the slaves themselves. Slavery in Africa, argued Burton, had not been invented by ‘foreigners’, such as his beloved Arabs, but by the Africans themselves, who regularly fought ‘internal wars, whose main object is capturing serviles [

sic

]’. He seemed blind to the fact that the treatment of domestic slaves, however benign, could not justify their brutal capture, or their long and often fatal journey to the coast.

10

Speke did not analyse the situation intellectually, but knew on an intuitive level that the entire trade – both domestic and export – should be suppressed because of the suffering and desolation it caused. Burton thought Africans contemptible and to blame for their misfortunes, despite his enthusiasm for recording their habits and customs. But while at times Speke could also write insultingly about them, he came to like and admire them.

11