Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (52 page)

At this moment of dire emergency for the missionaries, out of the blue a Russian-born explorer, Dr Wilhelm Junker, arrived at Mackay’s mission after a decade spent mapping the Welle and Ubangi rivers. Junker told the missionaries something momentous which Mackay realised at once might indirectly save him and his converts if he could only involve the British press. Apparently, Emin Pasha, the Anglo-Egyptian governor of Equatoria, Sudan’s most southerly province, was retreating south towards Lake Albert, pursued by the fundamentalist Muslim followers of the self-declared Mahdi or ‘Expected One’. Of humble Sudanese birth, Muhammad Ahmad, the Mahdi, had harnessed deep anti-Egyptian feelings in a movement that was part religious

jihad

and part nationalist uprising. Indeed, 10,000 of his followers had recently overwhelmed Khartoum and killed General Gordon, the Governor-General of the Sudan. Because Gordon had been a British national hero, his bloody death on the steps of his own palace had aroused great grief and fury in

Britain – the public’s indignation being the fiercer because the relief expedition sent by Prime Minister Gladstone had arrived just two days too late to save the besieged governor.

Muhammad Ahmad, the Mahdi.

Gordon’s death led to the downfall of Gladstone’s Liberal government, convincing Alexander Mackay that the new Prime Minister, the Conservative Lord Salisbury, would do anything in his power to ensure that Emin Pasha, Gordon’s last surviving governor, did not share his superior officer’s fate. And if Lord Salisbury chose to send a force to save Emin, the same soldiers could then go on to rescue the Christian missionaries and their converts, a mere 200 miles away in Buganda. Fortunately for Mackay he knew and liked Emin Pasha and had corresponded with him in the past. So now he reckoned that if he could get a letter to the Pasha and receive from him in reply a passionate appeal for British intervention in Equatoria and Buganda (which Mackay would then send on to the British press), Lord Salisbury would feel obliged to despatch a force to Equatoria to relieve the beleaguered Pasha.

Having found messengers prepared to run the risk of taking a letter to Emin at Wadelai on the Nile, Mackay sat down and wrote

as persuasively as he knew how. The result was the arrival of a reply several months later that exceeded his most sanguine hopes. Emin wrote of his desperate struggle for survival and vowed to hold out until he and his men were either annihilated or relieved. Mackay promptly entrusted Emin’s letter to the next caravan bound for Zanzibar and a few months later it was published in the London

Times.

13

But Lord Salisbury was no pushover and would disappoint both the Pasha and Mackay. The Prime Minister and his cabinet concluded that since Emin, who knew central Africa well, thought it impossible to reach the coast with the few thousand men at his disposal, there would be little point in sending a few thousand more to rescue him. An Anglo-Egyptian force of 10,000 men led by a British general, William Hicks Pasha, had recently been massacred by the Mahdi’s followers, so history might simply repeat itself; and, in any case, if a force did succeed in reaching Emin and then managed to enter Buganda, an enraged Mwanga would probably murder all the missionaries on its approach.

14

So the pragmatic Prime Minister sat on his hands.

But there

were

two people who refused to accept that nothing could be done for the missionaries and for Emin Pasha. They were Henry Morton Stanley and his close friend, the self-made shipping millionaire and philanthropist William Mackinnon. Stanley agreed to lead an expedition formed specifically to re-supply Emin Pasha and to rescue the missionaries, provided that Mackinnon succeeded in raising the £20,000 which he estimated would be needed to pay for a full-scale relief party. The Scottish entrepreneur produced the cash swiftly, enabling Stanley, who had been responsible in the first place for summoning Mackay to the shores of Lake Victoria, to play a crucial role in the bizarre and violent chain of events that would ultimately bring Uganda and the headwaters of the Nile within the purlieus of the British Empire. But before passing to these upheavals, the slightly earlier European advances in West Africa must be visited since they would exert a decisive influence on the way in which East Africa and the Nile basin were to be carved up.

TWENTY-EIGHT

Pretensions on the Congo

Samuel Baker had demonstrated, theoretically at least, to European rulers how African territories – even remarkably inaccessible ones – could be snatched by relatively few armed men and then held by means of forts, trading posts and alliances with local people. But thanks to Ismail’s precarious finances, the

khedive’s

plans for further southward advances soon juddered to a halt. So with the British government not quite ready to take over from the

khedive

in Egypt, Baker’s foray failed to kick-start a European scramble for colonies along the Nile and in East Africa. It was the sudden and surprising appearance of Stanley on the Atlantic coast, almost 3,000 miles from Egypt, that would do that – in an unexpected way.

The news that Stanley had reached the Congo’s mouth, at the end of his Nile quest, had caused worldwide excitement. But it was the impression this feat made upon one minor European monarch that would have the most lasting consequences. In ignorance of Leopold II of Belgium’s carefully concealed plan to pillage the Congo, Stanley was persuaded by the king to return there as his Chief Agent to set up (as Stanley thought) international trading stations on the river so the Congolese would be able to exchange their ivory, hardwoods, resins and gums for factory goods brought upriver by traders of all nations. In public the king had no trouble applauding Stanley’s promise ‘to open up the valley of this mighty African river to the commerce of the world … or die in the attempt’. But in private, and in reality, Leopold meant to close the Congo to all nations but his own, just as soon as he felt he could get away with it.

1

Between 1879 and 1884 Stanley built a road past the cataracts on the Lower Congo, launched steamers on the upper river

and built a string of trading stations for the Belgian king. This pioneering work would lay the foundations for the future Congo Free State and so constitutes an important episode in West African colonial history. But while Stanley was working on the Congo, significant events occurred there which would also have a direct bearing upon the competitive behaviour of European nations several thousand miles away in East Africa and along the Nile.

King Leopold II of Belgium.

In November 1880, while Stanley was building his road west of Stanley Pool, an Italian-born French naval officer, Lieutenant Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, walked boldly into his camp and introduced himself. With ambitions to extend their West African possessions, the French government had funded de Brazza to pioneer a route along the Ogowe river from the Gabon coast

to the River Congo in the region of the Pool. Although the Frenchman admitted that he had set up a small post on the north shore of Stanley Pool, Stanley took a liking to him and refused to believe Leopold’s warning that the young officer meant to found a French colony. Since Stanley wanted the river to be opened to the traders of all nations, de Brazza’s new French post did not annoy him, as it did Leopold.

2

But on 27 February 1881 Stanley learned something from two Baptist missionaries which made him feel a lot less friendly towards de Brazza. Apparently, in October 1880, before meeting him, the Frenchman had signed a treaty with Makoko, the most important paramount chief on the northern shores of the Pool. Furthermore, according to the missionaries, de Brazza was claiming this chief’s territory for France. Since de Brazza had assured Stanley that he had been sent to Africa by the International African Association, a philanthropic organisation founded by Leopold, Stanley was very angry to have been duped.

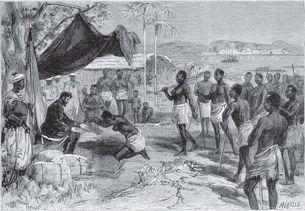

De Brazza welcomed at Makoko’s court.

In December 1881, he made a treaty with local chiefs to the south of the Pool. This secured for Leopold a crucial half-mile stretch of the bank at Ntamo near where the Congo flowed into Stanley Pool. Although no sovereignty was claimed, the French were effectively excluded from building at this strategically vital location.

3

During 1882 and 1883, to deny the French the best positions on the upper river, Stanley rapidly constructed four stations on the Congo above Stanley Pool. His heart was in this work since the French were protectionists, and Leopold, Stanley believed, favoured free trade. In June 1882, Stanley’s agents managed to negotiate a treaty with Chief Nchuvila of Kinshasa. On land leased by him at Ntamo and Kinshasa, the city of Leopoldville (now renamed Kinshasa) would rise in later years.

Since the Pool connected the Lower to the Upper Congo and lay at the head of any future railway, its possession would be indispensable to the government of any future Congolese state. So France would have to win control of this essential stretch of water in order to lay claim to the Congo. Later in 1882 the French parliament ratified de Brazza’s treaty with Chief Makoko, clearly signalling that they meant to snatch the Congo from Leopold. To forestall them the king began to employ British, rather than Belgian officers on the river, in the belief that the French would not dare provoke an incident with Great Britain. By the end of 1883, forty-one out of 117 clerks, storekeepers, engineers and officers were British.

4

When Stanley was on the lower river on his way to Europe – having been recalled by Leopold – de Brazza judged that the perfect moment had come to seize the southern shores of the Pool. He chose not to land at Leopoldville, where the garrison was commanded by a capable British Army officer, Captain Seymour Saulez, but at neighbouring Kinshasa, where the Briton in command was a young former apprentice tea broker, Anthony Bannister Swinburne. De Brazza crossed the Pool in late May 1884 with four canoes and about fifty French-trained Senegalese sailors, all armed with modern Winchester rifles and under the orders of Sergeant Malamine, the commander of the French

post on the Pool’s northern shore. De Brazza also brought his secretary, Charles de Chavannes, to draw up a treaty. Just outside the settlement, de Brazza’s men were forced to halt by Hassani, one of Swinburne’s Wangwana, who raised his rifle threateningly after Malamine had ordered him in Swahili to let them pass since ‘de Brazza was Swinburne’s master’.

Guessing that the Frenchman would not risk a shoot-out, Swinburne ran straightaway to Chief Nchuvila’s compound and implored him not to meet de Brazza’s party without him (Swinburne) being present. The young station chief then ordered his Wangwana to load their rifles and hide in the scrub outside their camp. They were only to emerge if the French began firing. Then, he walked calmly towards the uniformed Senegalese and invited de Brazza, Malamine and de Chavannes to join him in his wooden house for a glass of brandy. Despite Swinburne’s hospitality, a fierce argument soon raged about who had the right to occupy Kinshasa. With neither party giving an inch, Swinburne suggested they begin an immediate palaver with Chief Nchuvila to find out what

he

wanted. It would not be long before de Brazza discovered that the chief and his sons were ardent supporters of young Mr Swinburne and Stanley’s expedition – currently known as the International Association of the Congo (AIC). Two of the chief’s sons began to rant at the French intruders, and de Brazza demanded that the two men be punished for insulting him. Swinburne refused, pointing out that the chiefs had made it very clear that they would never recognise any flag but the AIC’s. Then he turned to de Brazza and said: ‘I have nothing more to say to you, so wish you good morning.’ De Chavannes claimed that under his breath Swinburne had then called the Tricolour a rag.

5