Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (47 page)

Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Richard Burton was another early visitor to the RGS. He came again on 29 November 1875, well-prepared for the debate on Stanley’s discoveries. But if Rigby had expected that ‘B the B’, as Speke had called Burton, would apologise for having poured scorn so groundlessly, for over a decade, on his travelling companion’s account of the Nyanza, he must have been thunderstruck to hear Burton say that he ‘still regarded it as possible that the Tanganyika might be connected with the Nile [because] by some curious possibility the Lukuga would be found to be the ultimate source’. Burton hypocritically ‘expressed his heartfelt sorrow that his old companion had not been spared … to see the

corrections

[my emphasis] which Mr Stanley had made with regard to his [Speke’s] wonderful discovery of that magnificent water that sent forth the eastern arm of the Nile’. The western arm, Burton still maintained, would spring from

his

Lake Tanganyika – his hope being that the Lukuga would flow into the Lualaba, which would in turn join the Nile somewhere above Lake Albert, as Livingstone had believed it would.

2

Meanwhile, in Africa, Stanley had not quite ruled out such a scenario. As he marched through Manyema towards the Lualaba, he still yearned for that river to be the Nile – not for Burton’s sake of course – but to vindicate the hopes of his honorary father, David Livingstone. Before crossing Lake Tanganyika, Stanley had been plagued by desertions so his party was now down to 132 individuals, most of them terrified by the dangers that might lie ahead on the river. Kalulu, the youth whom Stanley had rescued and educated, was one of the deserters. After he was recaptured, Stanley would not be able to forgive him. Yet, in the end, it would be clear that Kalulu’s decision to escape had been the right one. He would surely have reached adulthood, if he had only managed to avoid recapture.

3

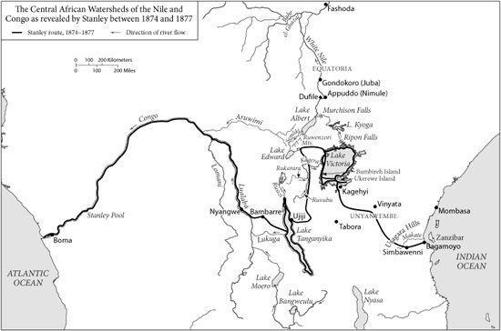

On 17 October 1876, the expedition arrived on the banks of the Lualaba, and Stanley saw, for the first time, an immense pale-grey river winding its way slowly northwards into the unknown, between densely wooded banks. For the sake of the Lualaba, Livingstone had sacrificed himself, but, like Cameron, had failed to follow it beyond Nyangwe. Stanley had no means of knowing how far it would flow to the north before deviating to east or west, declaring its kinship to the Nile or to the Congo.

The following day he met the most important Arab-Swahili slave trader in Manyema, Hamid bin Muhammad el-Murebi (whose nickname Tippu Tip was supposed to mimic the sound of bullets; a grandmother had been the daughter of a Lomani chief, explaining his African appearance). He had the power to guarantee or to deny Stanley the canoes and other supplies which were essential for his voyage downstream. So the explorer felt he had no choice but to do a deal with him, rather than be stopped from following the river. The Arab also had men to spare as an escort to protect Stanley’s people from hostile tribes along the Lualaba immediately to the north of Nyangwe. These tribes were dangerous to strangers because of slave raids made by men like Tippu Tip, but Stanley would still need protection and was prepared to pay him the amazing sum of $5,000 (the entire cost of his Livingstone quest) to accompany him with 140

armed men for sixty marches north of Nyangwe. If he failed to reach agreement with the Arab, Stanley knew he would fail in his mission. Cameron had tried to cut a similar deal, but Tippu Tip had turned him down. Stanley’s deal did not mark a lessening of his hatred for slave traders. In a despatch written at this time, he urged Britain to act militarily against ‘a traffic especially obnoxious to humanity – a traffic founded on violence, murder, robbery and fraud’.

4

Tippu Tip.

The agreement was that Tippu Tip’s men would part company with Stanley after about 200 miles, and thereafter the explorer and his 146 followers, only 107 of whom were contracted men, would take their chances on their own. Inevitably, death by drowning, disease, starvation, and by African attacks would reduce their numbers by journey’s end. Before marching out of Nyangwe with Tippu Tip on 5 November 1876 into the Mitamba forest, Stanley wrote to a friend admitting that he feared he might share the fate of the explorer Mungo Park, who had been speared to death on the Niger.

But I will not go back … The unknown half of Africa lies before me. It is useless to imagine what it may contain … I cannot tell whether I shall be able to reveal it in person or it will be left to my dark followers. In three or four days we shall begin the great struggle with this mystery.

5

For weeks, Stanley’s people and their Arab-Swahili escort struggled along the eastern bank of the great river, beneath the canopy of the tropical forest, sweating in the dark hothouse air. On this side of the river, it would be impossible for him to miss any eastward-flowing branch which the river might throw out towards the Nile via the Bahr el-Ghazal. Since the Lualaba seemed large enough to supply both the Nile and the Congo, Stanley still did not discount the possibility of such a branch existing: ‘It may be so, as there are more wonders in Africa than are dreamed of in the common philosophy of geography.’

6

After two weeks spent hacking their way through the forest, his followers embarked upon the Lualaba itself, having recently made the gruesome discovery of charred human bones near recently extinguished cooking fires.

7

But cannibals or not, Stanley was distressed to see men, women and children of the Wenya people running away whenever they caught sight of Tippu Tip’s men and his own.

In December, while still paddling due north, they were involved in a series of small skirmishes which Stanley foolishly dramatised as ‘fights’ in his despatches to the

New York Herald.

8

Two days after Christmas, Tippu Tip broke his agreement and returned to Nyangwe. He had just lost three of his wives to smallpox, and in a five-day period seven of his soldiers died of tropical ulcers and fever. Since they were now only 125 miles north of Nyangwe, rather than the 200 they had agreed to travel together, Stanley paid Tippu half the agreed sum.

9

In order to persuade his entire party to embark in the twenty-three canoes he had just bought for them, Stanley had to get Tippu Tip to threaten to shoot them if they did not. Otherwise, most would have begged the Arab to take them back to Nyangwe – such was their terror of sailing on the river. And who can blame them? From its banks, they often heard the cry: “

Niama, niama

[meat, meat]’, and the inhabitants of one village tried to catch an entire boat’s crew in a large net. ‘They considered us as game to be trapped, shot, or bagged at sight,’ wrote Stanley. But he knew there was nothing he could do to allay the suspicions his presence provoked. The slave traders had seen to that. So, whenever aggressively pursued by canoes propelled by more paddlers than his own and therefore faster, he felt obliged to shoot rather than let his vessels be boarded.

10

On 6 January, after travelling 500 miles due north from Nyangwe, they came to the first cataract in a chain of seven that extended for sixty miles. Now all his boats had to be taken out of the water and dragged overland past each one of these seven cataracts, most of which extended for several miles. The noise of the river crashing over rocks and funnelling through gorges was so loud that his men could not hear each other speak, even when standing side by side. Their progress along the falls took twenty-four days. Now at last the truth became apparent. Soon after passing the final cataract, Stanley realised that the river had turned sharply westwards.

Then, on 7 February 1877, for the very first time, he heard the river referred to as ‘Ikuta Yacongo’. This was an historic moment. Two years and two months into his extraordinary journey, Stanley had proved that the Lualaba was the Upper Congo and not the Nile. The Lualaba’s northward drive for a thousand miles from its source, where Livingstone had died, to the point where it turned decisively westwards would never again deceive geographers and explorers. But whether he would live to bring this news home in person, or ‘whether it would be left to [his] dark followers to reveal it’, was far from certain. He was still 850 miles from the Atlantic.

11

Speke’s case was proved, and Burton’s and Livingstone’s had been destroyed. Stanley was glad for Speke’s memory and deplored how the RGS had turned against him after his death. But his deepest emotions were reserved for:

that old, brave explorer … [and] the terrible determination which [had] animated him … Poor Livingstone! I wish I had the power of

some perfect master of the English language to describe what I feel about him.

12

But had Stanley really unravelled the entire mystery that had baffled every generation since the ancients? When he had expressed his belief that the Kagera was probably ‘the parent of the Victoria [White] Nile’, had he meant to downgrade the importance of Speke’s outlet at Ripon Falls? In a despatch to the

New York Herald

dated August 1876, Stanley repeated the question originally posed by Speke: ‘What should be called the source of a river – a lake which receives the insignificant rivers flowing into it and discharges all by one great outlet, or the tributaries which the lake collects?’

13

Stanley suggested that if the tributaries were favoured, it would be but one step further to see ‘sources’ in the moisture and vapour which the clouds absorb. So he gave his vote to Speke.

Speke had first seen the Kagera in 1861, when staying with King Rumanika, and had called it the Kitangule. The explorer knew that this important river formed a series of small lakes, and deduced that its origins lay in springs and in rain precipitated on the mountains of Rwanda. One evening, he glimpsed what he called ‘bold sky-scraping volcanic cones’ fifty miles to the west. Showing astonishing insight, he described these mountains as ‘the turning point of the central African watershed’, as indeed they are, along with the more northerly Ruwenzori Mountains.

14

So what of the Kagera and its highland sources, which Speke had dismissed with his rhetorical question about the respective merits of ‘one great outlet [and] the tributaries which the lake collects’? It would not be until 1891 – when Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania were classified as constituent parts of German East Africa – that an Austrian ethnographer and explorer, Dr Oscar Baumann, traced what appeared to be the most southerly tributary of the Kagera, the Ruvubu, to a point in southern Burundi about fifty miles to the south of the northern tip of Tanganyika and twenty miles east of the lake. In 1935, Dr Burckhardt Waldecker, who had fled the persecution of the Jews in Nazi Germany, found

a marginally more southerly source on nearby Mount Kikizi. But being further south was not the only quality required to gain the prize. In 1898, Dr Richard Kandt, a German physician, scientist and poet, had traced the main line of the Kagera – judged by volume of water – via its Rukarara tributary to Mount Bigugu, near the southern end of Lake Kivu. This spring was alleged to be thirty-six miles further from the Mediterranean than the Kikizi source – a tiny superiority given the Nile’s total length of just over 4,200 miles. But given the huge technical difficulty of calculating the length of such a long river, a definitive result will always elude geographers. A complex delta and the shifting channels in Lake Kyoga and the Sudd’s floodplain pose particular problems.

15

During the last fifty years, the line of the Rukarara has been shown to extend a little further into the Nyungwe Forest than Kandt had demonstrated. But in a marshy area of many springs, it is hard to pick out an unassailable Kagera source. Although Neil McGrigor and his Anglo-New Zealand party claimed to have added another sixty miles to the Nile with the help of GPS in 2006, it should be noted that similar claims to have extended the river beyond Kandt’s source had been made in the 1960s on behalf of Father Stephan Bettentrup, a German priest living in Rwanda. Then, at the end of the last decade, a Japanese party from Waseda University also claimed to have outdistanced Kandt.

16

In my opinion, to add a few miles to the shifting upper springs and streamlets of the Rukarara does not dethrone Richard Kandt, let alone threaten the achievements of the Victorian explorers who entered Africa without maps, wheeled transport, or effective medicines, and yet solved the mystery of the entire central African watershed.