Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (51 page)

En route

to Fatiko, Baker sought out Kabarega’s rebel uncle, Rionga, on his island in the Nile, to pledge to him Egypt’s future support in his struggle to supplant his royal nephew.

13

Travelling back to Khartoum on the Nile, after defeating a determined group of slave traders who attacked his fort at Fatiko, Baker intercepted three boats containing 700 slaves -hardly confirming his later claims to have rid the river of the trade in human beings.

14

In fact, the overland movement of slaves to Darfur and Kordofan – following the discovery of the Bahr el-Ghazal waterway – had for a decade dwarfed the number of slaves being transported on the Nile by a ratio of six or seven to two.

15

From Ismailia, Sir Samuel wrote to his brother John, intending the letter to be released to the press:

All obstacles have been surmounted. All enemies have been subdued -and the slavers who had the audacity to attack the troops have been crushed. The slave trade of the White Nile has been suppressed – and the country annexed, so that Egypt extends to the equator.

16

Far from being subdued, Kabarega had been left as independent and obdurate as before, and al-Aqqad and the other slavers had merely received a temporary check at Fatiko. Nor had Baker ever travelled as far south as the Equator – let alone ‘annexed’ anything there. Florence’s hyperbole exceeded her husband’s. ‘After great difficulties and trials,’ she told her sister-in-law, ‘we have conquered and established a good Government throughout the country’.

17

Khedive Ismail, Baker’s employer, was not taken in by the self-promotion, declaring that ‘the success [of the expedition] has been much exaggerated’ and that Baker, though ‘brave’ had been ‘too prone to fighting … giving rise to a general feeling of hostility towards Europeans and my government in Upper Egypt’.

18

Nevertheless, on returning to Britain, Baker’s optimistic letters were read aloud in both Houses of Parliament, and caused

The Times

to gush: ‘The undertaking stands out in the tame history of

our times as a bold and romantic episode … Nothing recorded of the Spaniards in Mexico exceeds in stirring interest the story of the retreat from Bunyoro.’

19

The adventurous aspects of Sir Samuel’s enterprise even dazzled the Liberal Foreign Secretary, Lord Derby, who wrote praising him for ‘having extended British influence in Egypt’ and for accelerating ‘the rapid progress which we are making in opening-up Africa’. It was almost as if, in 1874, Derby foresaw that within a decade Britain would dismiss the bankrupt

khedive

and become the new ruler of Egypt and its territories on the Nile.

20

But while this Liberal statesman succeeded in sensing the direction in which the winds of history were starting to blow, he failed to recognise that Baker’s recipe for creating new colonies, with a few steamers and a regiment or two, had little to do with adventure and a lot to do with brushing aside legitimate African rulers, whose only crime was to have indicated that they wished to remain independent in the face of superior might. In reality, Baker’s ‘adventurous’ retreat from Bunyoro had been a victory for Kabarega, the ‘unmannerly cub’. While Baker could justifiably claim to have been attempting to liberate the Upper Nile from the slave trade, he could not claim to have been similarly motivated in his invasion of Bunyoro, which had never been devastated and turned into an anarchic killing field by the slavers.

To many people in public life in Europe, Baker’s expedition was the first to reveal the strategic and economic possibilities of alien rule in tropical Africa. It therefore brought closer the ‘Scramble for Africa’. Baker claimed that by creating peaceful conditions on the Upper Nile, he had opened the way for immense crops of cotton, flax and corn to be grown in future, guaranteeing lasting prosperity to the region’s inhabitants and profit to those who came to trade with them.

21

He had certainly focussed attention on Africa just when the Kimberley diamond fields were providing would-be colonists with another tempting reason to give it their attention. On 9 December 1874, the editor of

The Times

gave voice to sentiments which would have enraged Kabarega and Mutesa had they ever heard about them:

It is not long since central Africa was regarded as nothing better than a region of torrid deserts or pestiferous swamps … there now seems reason to believe that one of the finest parts of the world’s surface is lying waste under the barbarous anarchy with which it is cursed.

Sadly, Baker’s unsuccessful efforts to make Equatoria a reality and to extend Egypt’s borders – and thus Sudan’s – as far south as Bunyoro would be taken up by others with greater success and would prove utterly disastrous to the wider region in the long term.

TWENTY-SEVEN

An Unheard of Deed of Blood

Henry M. Stanley had visited Mutesa, the

kabaka

of Buganda, in April 1875, while trying to determine whether Livingstone and Burton had been right to dismiss Speke’s claim to have located the source of the Nile in Lake Victoria. So the Nile search was responsible for this nation-changing meeting between the

kabaka

and the explorer. Although Stanley would not say so, his success in persuading the king to invite Christian missionaries to come to Buganda owed less to Mutesa’s interest in Christ’s teaching, than to the monarch’s expectation that he would be able to buy breech-loading rifles from any Europeans who might choose to come to his country as a result of his invitation. Mutesa had long feared that without such weapons to help him, the Egyptians would ‘eat’ his country.

Stanley had been shocked to find that Arab slave traders at Mutesa’s court were buying enough slaves from the

kabaka

to make Uganda, in his words, ‘the northern source of the [East African] slave trade’. So his purpose in asking Mutesa to summon Christian evangelists had been to counter the influence of slave-trading Muslims at court.

1

The arrival in Buganda of the white-suited, Tyrolean hat-wearing, Alexander Mackay of the British Church Missionary Society (CMS) in November 1878 opened a new chapter in the history of that country and its neighbouring kingdoms. Seven missionaries had been sent a year earlier but only one survivor had been there to greet Mackay. Two had been killed near the lakeside by fishermen, one had died of fever and three had retreated to Zanzibar to recuperate from fever.

2

Mackay was small, dapper, resourceful, and very courageous. As a former engineer, he was well placed to teach boat-building and carpentry

and to set up a printing press. He was also a knowledgeable horticulturalist. In 1879, he started to translate St Matthew’s Gospel into Luganda, along with short texts and prayers. In the same year, a group of French ‘White Fathers’ arrived under their leader Father Simeon Lourdel.

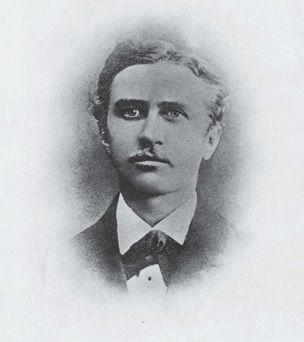

Alexander Mackay.

During the early 1880s the British and French missionaries made their first converts, mainly among the young pages sent to court by their families to learn leadership. These boys and other youngsters serving the missionaries made it fashionable to learn to read. They would become known collectively as ‘readers’.

A number of chiefs also became converts and formed a distinct group at court. By 1884, there would be roughly a hundred Baganda Christians, with four times that number being converted in the next two years.

3

Throughout this extraordinary process, which was almost without parallel in Africa, Mutesa remained ominously aloof and expressed anger that the missionaries

only

taught his people about God, although Stanley had led him to believe that they would teach the Baganda ‘how to make powder and guns’. His people needed this knowledge, he explained to Mackay, because the Egyptians were ‘gnawing at [his] country like rats’.

4

The Arabs already resident at court had everything to lose if the missionaries established themselves, since they would dissuade Mutesa from continuing the slave raids outside his borders, which enabled him to pay the slave traders with slaves for their cloth and other goods. Naturally they did their best to poison Mutesa’s mind against the new arrivals, saying that the white men were only interested in ‘eating up the country’ and were fugitives from justice in their own lands.

5

By 1884, Mutesa was dying of an incurable disease, and on the advice of his

ngangas

he sacrificed thousands of people to appease the ancestral spirits. As many as 2,000 were executed in a single day. Mackay called him ‘this monster’ and declared: ‘All is self, self, self. Uganda exists for him alone.’

6

The

kabaka

was succeeded by his headstrong, nineteen-year-old son, Mwanga, who under Mackay’s restraining influence decided not to murder his brothers, as his predecessors had traditionally done. But Mwanga remained deeply suspicious of the missionaries. He had heard that white men were moving inland from the East African coast, making treaties as they went. These were Germans led by the imperialist Dr Karl Peters. Mwanga had also heard that the British had taken power in Egypt after a big battle there. Since he was unsure of the differences between European nations, he gained the impression that these white men had put their heads together to steal his country. It was a natural conclusion to have drawn.

General Gordon, the Governor-General of the Sudan, had sent a small party of soldiers to Uganda in 1876, and now there was news of another Briton unexpectedly arriving at the north-east corner of Lake Victoria. Joseph Thomson had just pioneered a route through Masailand, and as ill-chance would have it, his arrival convinced Mwanga that his country was being overwhelmed from all directions. When the missionaries said they only wanted to teach his people their religion, he did not believe them and still suspected that they wanted their countrymen to come and take away his kingdom.

7

Mackay learned that several chiefs who had become Muslims were urging Mutesa to kill the Christian converts and drive the missionaries out of the country. The slave traders – named by Mackay as Kambi Mbaya (Rashir bin Shrul) and Ahmed Lemi – were apparently foremost in urging the

kabaka

to kill the missionaries.

8

In January 1885, Mwanga arrested Mackay with three of his young readers. He was placed under guard, but his protégés were dragged off to a swamp outside the royal town of Mengo. Mackay hurried to the court and protested that they were guilty of no crime, but on Mwanga’s orders the boys’ arms were hacked off by his chief executioner, and then they were slowly roasted on a spit. After being released, Mackay bravely upbraided Mwanga for this appalling act.

9

The whole mission was now in acute danger.

It was at this disastrously inauspicious moment that the jovial Bishop James Hannington arrived with fifty followers at the north-eastern corner of the lake having travelled through Masai country on Mwanga’s forbidden route. The adventurous and optimistic Oxford-educated cleric had been sent to Buganda by the CMS to take up residence as the first Bishop of Eastern Equatorial Africa. He would never reach his destination. On 21 October 1885, he was arrested in Busoga, with his fifty Wang-wana porters. A shocked Mackay went to the court on three consecutive days to petition Mwanga for the bishop’s life. His French rival, Father Lourdel also pleaded for mercy to be shown. None would be. After eight days of incarceration in a dark and

verminous hut, Bishop Hannington was taken out into a forest clearing, stripped naked and stabbed to death along with all his porters, except for four who managed to escape. One of them reported Hannington’s last words as having been: ‘Tell the king that I am about to die for his people, that I have bought the road to Buganda with my life.’

10

For several months, Mackay came close to leaving Buganda, but the situation gradually calmed down and he resumed his secret conversions.

Then, on 30 June 1886, Mwanga struck in earnest, arresting and executing forty-five Protestant and Catholic converts in almost equal proportions. Several he strangled with his own hands. Others were castrated, before being burned alive. The chief executioner reported to the king that ‘he had never killed such brave people before, and that they had died calling on God’. Mutesa’s response was to say with a laugh: ‘But God did not deliver them from the fire.’

11

Mackay wrote in his journal: ‘O night of sorrow! What an unheard of deed of blood! Surely if they fear invasion, they must see that by such an act they give the imaginary invaders a

capital

excuse for coming in force … ?’

12