Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (54 page)

Mackinnon viewed the despatch of the expedition with acute anxiety as well as with excitement. If Stanley were to arrive too late to save Emin and the missionaries, Peters would reach Uganda first; and then the sources of the Nile, and Equatoria, could be lost to Britain forever.

THIRTY

‘Saving’ Emin Pasha and Uganda

Emin Pasha.

In August 1887 Stanley was on the southern shores of the Pool with just under 800 men, two tons of gunpowder, 100,000 rounds of Remington ammunition, 350,000 percussion caps, 50,000 rounds of Winchester ammunition and a Maxim gun, all to be handed over to the beleaguered Emin Pasha, providing he was still alive and could be found. Because King Leopold was still paying Stanley a retainer under their old contract, his former Chief Agent had been obliged to agree to travel to Lake Albert (where the Pasha was believed to be) along the Congo, rather than by the shorter overland route through East Africa. The Belgian king wanted Stanley to approach Lake Albert from the west because from that direction he would be able to extend

the boundaries of his Congo Free State by pioneering a route to the lake through the unexplored Ituri Forest in eastern Congo. As an inducement the king had offered Stanley the use of all his steamships currently on the Upper Congo.

1

Stanley would then be able to transport his men, and the supplies intended for Emin, by water for a thousand miles upstream to the east, meaning that his porters would then only have to carry their loads overland for 400 miles to Lake Albert.

Stanley knew that Leopold also expected him to lure Emin Pasha away from the service of the Cairo-based Anglo-Egyptian government with the offer of a huge salary. Equatoria could then (hoped Leopold) be swallowed up by his already bloated Congo Free State. But Stanley had no intention of allowing this to happen. The plan he had hatched with Mackinnon was that Emin and his 3,000 soldiers should be persuaded to relocate, beyond the reach of the Mahdi’s Sudanese

jihadists,

in a region just to the east of Buganda where they would be well-placed to take control of that country and stop the Germans making it their colony.

However, Stanley’s plan depended upon his managing to reach Emin first – before the Mahdi’s forces could kill him, and (if he survived that fate) before Karl Peters could persuade the German-born Pasha to throw in his lot with his fellow-countrymen and hand Equatoria and Buganda to the Kaiser.

At this early stage it was essential that Stanley manage to keep his force together so that by the time he had rescued Emin, and reached the missionaries in Buganda, he would still have enough men to be able to act independently on Mackay’s behalf, should the need arise. So when, on arrival at Stanley Pool, he learned that three of the king’s four steamers were damaged or irreparable, and that the largest one, the

Stanley,

was currently being repaired, he was devastated.

2

Even if he could persuade the two largest missionary societies in the country to lend him their steamers, he would now be delayed for months and would probably reach Emin too late to save him.

Stanley knew that his namesake steamer, the

Stanley,

once repaired, would have to make several trips towing barges

back and forth along the Congo before all his 800 men could be disembarked nearly a thousand miles upstream. Even with borrowed steamships a minimum of two trips from west to east would have to be made. So to have any chance of arriving in time to save Emin, he would have to split his expedition into two contingents and set up a base camp a thousand miles away to the east. A Rear Column of several hundred men would then be left behind to look after the bulk of the expedition’s stores, while a fast-moving, lightly equipped Advance Column marched eastwards to find Emin Pasha and deliver enough guns and ammunition to enable him to fight off his enemies.

Steamship on the Upper Congo.

When setting up his relief expedition, Stanley had for the first time in his life decided to employ gentlemen as colleagues, rather than working-class men, as on his previous journeys. Almost from the beginning, he regretted the change. Major Edmund Barttelot, whose father was a baronet, and who had come highly recommended by senior army officers, turned out to be shorttempered and inclined to lash out at Africans for no good reason with a metal-tipped stick. Though Stanley had grave doubts

about entrusting the Rear Column to him, he knew that, as second-in-command of the expedition, the major could not be expected to serve in a detached contingent under anyone’s orders but his commanding officer’s. It reassured Stanley somewhat to know that Barttelot’s closest friend on the expedition would be left behind with him. This popular sportsman and ethnographer, James Sligo Jameson, was a member of the Irish whiskey family, and his cheerful presence seemed to exert an influence on his colleagues that was almost as soothing as the drink that had made him rich. Barttelot would have 260 Africans under him, mainly Wangwana and Sudanese, to guard the expedition’s heavy stores. Stanley supervised the construction of a stockade and ditch around their camp, and told Barttelot that if Tippu Tip kept his promise to provide him with 600 carriers, the Rear Column would soon be marching eastwards in the footsteps of the Advance Column. If porters could not be obtained, then Barttelot must either stay where he was until Stanley could return for him, or he should weed his stores and march with as many porters as he could lay his hands on.

3

Barttelot’s camp was just outside a village called Yambuya on the Aruwimi river. Inside his stockade there was plenty of food, both preserved and fresh.

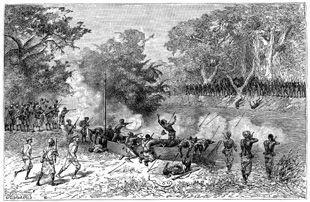

Lieutenant Stairs hit by an arrow.

On 28 June 1887 Stanley marched eastwards from Yambuya at the head of 389 men, less than half the number he had brought to Stanley Pool. Ahead lay hundreds of miles of unexplored jungle inhabited by villagers whose only encounter with outsiders had been with Arab-Swahili slave traders. To protect them from the slavers, cunningly disguised pits had been dug in the path, and small sharpened sticks with poisoned tips had been stuck in the ground. Anyone injured by these spikes would die within days.

4

Shortly after encountering these traps, Stanley and his men found the way ahead blocked by 300 warriors with drawn bows. They stood at the end of a section of path that had been widened and sewn with scores of tiny poisoned skewers, concealed beneath a carpet of leaves. While these barbs were being carefully pulled up, a hail of arrows fell on Stanley’s waiting men, who fired back with their rifles. Now there would be no hope of buying food for many miles to come.

5

In mid-August, Stanley’s most talented young officer, Lieutenant William Stairs, was struck by an arrow just below the heart. Dr Thomas Parke, the expedition’s medical officer, found Stairs in shock, blood pouring from his chest. All around he could hear the ‘pit, pit, pit’ of arrows dropping into the undergrowth. After injecting water into the wound, Parke bravely sucked out the poison. Stairs survived, but two other men hit at the same time died horribly from lockjaw.

6

By the end of the month Stanley’s carriers were eating nothing but green bananas and plantains – a wholly inadequate diet for men carrying heavy loads. In seven days, the expedition had lost thirty porters through death and desertion. As he marched beside the Aruwimi river, Stanley shot a man in a canoe as he was in the act of firing an arrow. In this man’s boat, the explorer found a dozen freshly poisoned arrows and a bundle of cooked slugs. This was an indication of how little game there was in the forest.

7

Men began to starve, and Captain Nelson, one of Stanley’s officers, had to be left behind in a temporary camp with fifty-two Africans who were incapable of walking any further. Their chances of surviving appeared to be very slight.

8

Stanley emerged from the forest a hundred miles from Lake Albert, with the Advance Column reduced to 175 men. This was 214 less than the 389 who had marched out of Yambuya four months earlier. On 14 April 1888, several days march from Lake Albert, Stanley heard from members of the Zamboni people that ‘Malleju’ (‘the Bearded One’) had recently been sailing on the lake ‘in a big canoe, all of iron’.

9

Two weeks later, the Pasha’s steamship anchored just below Stanley’s camp. Emin turned out to be a small, slim man in a red fez and a well-ironed white linen suit. He was bearded, bespectacled, and his face looked, thought Stanley, Spanish or Italian rather than German. Emin was said to command the loyalty of about 3,000 men, and to have fought off the Mahdi and his followers, unlike poor Gordon. But at their first meeting Stanley could detect ‘not a trace of ill-health or anxiety’ in his demeanour, and this worried him.

10

According to the Pasha’s own version of events, mailed to friends in Britain two years earlier, he and his men had survived a period of intense

jihadist

pressure.

Deprived of the most necessary things, for a long time without pay, my men fought valiantly, and when at last hunger weakened them, when after nineteen days of incredible privation and suffering, their strength was exhausted, and when the last leather of the last boot had been eaten, then they cut a way through the midst of their enemies and succeeded in saving themselves.

11

Yet, now, Emin and his officers appeared to be fit and well – a condition far removed from the traumatised state in which Stanley and his men found themselves. The Pasha seemed to have lied about his true situation. But when he responded enthusiastically to Mackinnon’s plan to resettle him and his men in the district just north-east of Lake Victoria, Stanley and his officers were able to feel that their sufferings had not been pointless. It now seemed likely to Stanley that he would soon be making a treaty with Kabaka Mwanga on behalf of Mackinnon’s company, before Karl Peters could enter Buganda.

12

Unaccountably, during the coming weeks, the Pasha failed to confide to Stanley any of the secret fears that were tormenting

him – the worst being that the Mahdi’s

jihadist

followers had already infiltrated his two regiments, making mass mutiny a terrifying possibility. Instead, Emin pretended that his position was stable enough for Stanley to feel secure about marching east to make contact with his Rear Column, while Emin travelled to Wadelai, north of Lake Albert, to ballot his men on whether they wished to relocate. Stanley had become increasingly worried about Barttelot and Jameson and was delighted that a suitable moment seemed to have arrived for him to find out if they were all right. Having lost so many men, he badly needed the services of the Wangwana who had been left behind with the Rear Column. Without an increase in his numbers, his opportunities for independent action in Buganda would be severely limited.