Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (50 page)

Baker finally escaped the Sudd seven months after first entering it, and only managed to reach Gondokoro (Ismailia, he would shortly rename it) on 14 April 1871.

1

By then there were only two years of his contract left to run, but at least he had arrived at the northern frontier of the vast territory over which he was expected to establish Egyptian rule. His

firman

from the

khedive

authorised and instructed him:

To organize and subdue to our authority the countries situated to the south.

To suppress the slave trade. To introduce a system of regular commerce.

To open to navigation the great lakes of the Equator and to establish a chain of military stations and commercial depots, distant at intervals of three days march.

2

This absurdly ambitious programme largely rested on his ability to reach an understanding with local Africans. He had hoped that the tribe in the neighbourhood of Gondokoro, the Bari, would gratefully accept his protection against the agents of the foremost slave trader in the region, Muhammad Ahmad al-Aqqad. He could not imagine they would not. But to his horror, he found that the Bari chief, Alloron, had recently allied himself with the slavers – his people voluntarily acting as al-Aqqad’s porters and mercenaries. So when Baker tried to buy foodstuffs, he was turned down. Evidently, it suited the interests of the Bari to gain immunity by coming to an accommodation with the ruling caste of Arabs permanently settled in the south. Baker had disliked these people on his earlier passage through their territory and now pronounced them ‘naturally vicious and treacherous’.

3

But though the Bari posed a serious problem, Baker experienced a worse one in his own camp, as Florence confided to her diary: ‘I must confess that I am rather disgusted with the whole expedition together with the natives, and as to the soldiers, they are perfect brutes in every way – I know it worries Sam very much to have to command such troops.’ Florence was shocked to hear the soldiers boasting of the numbers of Africans they had killed. One man deserted after breaking the sight on his rifle, and when recaptured, Baker sentenced him to a horrifying 200 lashes. Another received the same punishment for the far greater crime of murdering a prisoner. Baker was even shamed at times by members of his scarlet-shirted, èlite corps of black Sudanese Arabs, whom he had affectionately nicknamed the ‘Forty Thieves’. Florence saw one of them capture a girl of ten in order to make her his slave. When told what she had seen, Baker tore off the man’s clothes, took away his gun and told him he would be shot if he offended again.

4

Baker genuinely wanted to end the slave trade

and be seen as a liberator by Africans, but their natural dislike of his association with the slave-owning Egyptians doomed his efforts from the start.

Nevertheless, in May 1871, Baker hoisted the Egyptian flag over Gondokoro, renaming it Ismailia and simultaneously proclaiming the surrounding country – as far south as Buganda and Lake Albert – to be part of a new Egyptian province which he called ‘Equatoria’. This would prove a highly significant moment in the region’s history.

Raising the flag at Gondokoro (from Baker’s

Ismailia).

By December, Baker had violated his own principles and stolen corn and cattle from local tribesmen in order to feed his hungry soldiers. But the amount of food captured was too little and he had no alternative but to order 800 men back to Khartoum, with 300 of their ‘dependents’. After trying for nine months to impose Egyptian rule on the Bari, he was forced to move south with a mere 502 soldiers and fifty-two sailors, leaving Alloron’s people as determined in their opposition as they had been when he had first arrived.

5

But when Baker arrived at Fatiko – seventy-five miles north of Karuma Falls – his luck briefly changed. The local people, the Acholi, sided with him against the local Arab slave traders and helped him to obtain porters for the rest of the journey to Bunyoro. To reward them, he garrisoned local forts and enabled the Acholi to remain independent at a critical time. Today, Baker is revered in Acholi traditions, as is his wife Florence, who is still known as

Anyadwe,

or ‘Daughter of the Moon’, on account of her long blonde hair.

6

But, despite the support of the Acholi, by the end of 1871 Baker had abandoned any idea of incorporating Buganda within Equatoria. However, he still hoped to achieve this feat with Bunyoro. But given how much he had been mistrusted by Kamrasi, the previous

omukama

of Bunyoro, he was naive to imagine that he might somehow pull the wool over the eyes of his successor, Kabarega.

Kabarega’s return visit to Baker (from Baker’s

Ismailia).

Baker reached Masindi, Bunyoro’s present capital, on 25 April 1872. Since he only had an escort of a hundred men, he ran the risk of being detained or even murdered should Kabarega

decide that he had come to steal his country. But his first meeting with the

omukama -

whom he described as ‘very well clad, in beautifully made bark-cloth striped with black’ – seemed to go well. But when the twenty-year-old Kabarega returned the visit, nothing that Baker could say would persuade the young man to enter his hut. Clearly the monarch suspected possible foul play. An incensed Baker called him ‘an unmannerly cub’ and ‘a gauche, undignified lout’. The cub was in fact the twenty-third of his dynasty and had come to the throne after his father’s death, as the successful claimant after a bloody succession struggle.

7

Kabarega could not reasonably be blamed for being suspicious of a man whom his father had mistrusted, and who came as the representative of a distant government. But in reality Baker was the one who had walked into danger. A crowd of 2,000 people had accompanied Kabarega, ‘making a terrific noise with whistles, horns, and drums’. The king brushed aside talk of trade and civilisation, and told Baker that all he needed was military help against his rebel uncle, Rionga.

On 14 May, Baker, in his own words, ‘took formal possession of Unyoro in the name of the Khedive of Egypt’. This involved nothing more troublesome than putting on his governor-general’s uniform, parading his men, and then hoisting the Egyptian flag. In response to this insulting ceremony, Kabarega sanctioned the construction of huts and fences which hemmed in Baker’s campsite on both sides. He also declined to cut back the long grass which offered cover to any warrior who might wish to approach the camp without being seen.

8

On 31 May, Lieutenant Julian Baker

RN,

who had come to Africa as his uncle’s second-in-command, foolishly led most of the expedition’s soldiers into Kabarega’s town to drill them in an open space. Florence described the

omukama

’s response to this tactless provocation: ‘In about ten minutes I should think that quite 5,000 or 6,000 men turned out with their shields and arms and not one of the spears had a sheath on.’ The massacre of Baker’s entire party seemed imminent. Somehow remaining calm, Baker waved to a senior chief whom he recognised in the armed

throng, and walked towards the lowered spear tips, calling out through his translator: ‘Well done. Let’s all have a dance!’

9

He then ordered his scratch band to play and told his men to dance, which they did to the bafflement of the warriors. As the dancing continued, Baker ordered some men to creep forward with fixed bayonets, covering his flanks. Then, feeling rather more secure, he demanded to see Kabarega. The young king duly appeared and called off his warriors.

Baker knew that his quick-thinking had only gained him a little time. Kabarega believed with good reason that Baker meant ‘to eat’ his country, and not simply trade with him. So the young ruler’s next move, a week later, was to try to kill both the Bakers and their men with a gift of poisoned cider and grain. This attempt was foiled by Florence, who immediately mixed an emetic with vast quantities of mustard and salted water.

10

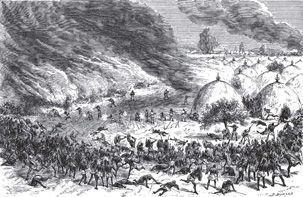

The ‘Battle of Masindi’ (from Baker’s

Ismailia).

The next morning Baker was shot at by men creeping up close through the long grass. His sergeant walking just behind him was hit in the chest and died on the spot. Another member of the ‘Forty Thieves’ was hit in the leg. Managing to summon sixteen

of his èlite corps with a bugle call, Baker ordered them to return fire. Meanwhile other men were told to set fire to Kabarega’s town, including the

omukama

’s audience hut. Monsoor, Baker’s favourite officer, was killed early in the fighting, along with three others. ‘I laid his arm gently by his side,’ wrote Baker, ‘for I loved Monsoor as a true friend.’ Throughout the fight, Baker was plied with loaded rifles by Florence, whom he called his ‘little colonel’. She also fired rockets into the town.

11

Four days later, the Bakers had no choice but to evacuate Masindi, although they knew that this was an acknowledgement of total failure.

The retreat to Fatiko (from Baker’s

Ismailia).

During the march to Fatiko, through many miles of tall grass, his column suffered numerous ambushes, leading Florence to vow that if her husband died, she would shoot herself rather than risk capture. The boy leading Baker’s horse was transfixed by a spear, and crawled up to him to ask: ‘Shall I creep into the grass, Pasha? Where shall I go?’ The next moment, he fell dead at his master’s feet. Baker’s greatest fear was that Kabarega’s army would overwhelm his men by force of numbers. Luckily for him, he managed to keep ahead of his pursuers. Even so, the losses on

the retreat from Masindi were ten killed and eleven wounded -heavy casualties for a force barely a hundred strong.

12