Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (23 page)

As Speke and his men followed Maula across a swampy plain towards the deep and strongly flowing Kagera river, he sensed that what he had been told about the Kagera on his first visit to the Nyanza had been right – namely that this was the lake’s principal feeder and that it rose far to the west in the Mountains of the Moon.

54

This feeling was not entirely intuitive, since in June 1858 Snay bin Amir had told him that he had ‘found it emanating from Urundi, a district of the Mountains of the Moon’.

55

In fact it originated well to the south of the Ruwenzoris (Mountains of the Moon) from two distinct sources in remote highland regions of Rwanda (close to Lake Kivu) and Burundi (close to Lake Tanganyika), but was, nonetheless the Victoria Nyanza’s main provider.

Speke wrote in his journal at the start of his march to Buganda: ‘I am perfectly sure … that before very long I [shall] settle the great Nile problem for ever.’ But this would depend entirely upon how he fared in Buganda, where, unknown to him, the

kabaka

had just sacrificed over 400 people in a vast ritual massacre to celebrate the coming of the white man. Kabaka Mutesa possessed the largest army in central Africa and was ruler of a kingdom that had been centralised and socially stratified since the fifteenth century. Rumanika warned Speke that Mutesa hated Bunyoro and its king, Kamrasi, and therefore never let anyone leave his country travelling in a northerly direction. This would make following any river north from Buganda extremely dangerous. In any case, Speke knew that he would be taking his life in his hands by placing himself in the power of an unpredictable feudal autocrat. But he had never lacked courage, as he was about to show many times during his long sojourn in Buganda.

56

NINE

As Refulgent as the Sun

During Speke’s six-week march to Buganda, as he came closer to the Nyanza, he and his men had to wade chest deep across a succession of swampy valleys where the water’s surface was only broken by large termite mounds, each topped with its own euphorbia candelabra tree. Towards the end of January, for the first time on this journey, he caught a glimpse of the glittering Nyanza from a place called Ukara; but neither on this occasion, nor when he came closer still on 7 February, did he choose to visit the lakeside itself to check whether the water seemed to be continuous. Certainly, he was restricted by the orders of his royal escort, but this lack of scientific thoroughness would come to haunt him later. Possibly he took it for granted that the lake was one immense inland sea because everyone he met said that it was.

1

In late January, after sending messengers to the

kabaka

to learn his wishes, Maula – who, unknown to the explorer, was Mutesa’s chief spy and torturer – told Speke that it would be ten days or more before they would be able to continue their journey and in the meantime he meant to visit friends. While he was gone, local villagers subjected Speke to two days and nights of ‘drumming, singing, screaming, yelling and dancing’. In their own eyes, they were frightening away the devil – aka the ghostly-looking white man – though Speke gave no indication that he made the connection. After several days of this hubbub, he was delighted to receive an unexpected visit from N’yamgundu, the brother of the dowager queen of Buganda. This nobleman promised to return at sunrise to escort him and his followers to Mutesa’s palace.

When N’yamgundu failed to turn up early next morning, Speke ordered Bombay to strike his tent and begin the march. Bombay

objected on the excellent grounds that without N’yamgundu, they had nobody to guide them. Frustrated and disappointed, Speke shouted: ‘Never mind; obey my orders and strike the tent.’ When Bombay refused, Speke pulled it down over his head. ‘On this,’ wrote Speke, ‘Bombay flew into a passion, abusing the men who were helping me, as there were fires and powder boxes under the tent.’ But Speke was beyond reason. Recalling all the insults, delays, untruths, disloyalties, thefts and losses he had endured without venting his fury, Speke’s self-control finally cracked. ‘If I choose to blow-up my property,’ he roared, ‘that is my look-out; and if you don’t do your duty I will blow you up also.’ Bombay still refused to obey him, so Speke delivered three sharp punches to his head. Bombay squared up as if about to fight back, but changed his mind and did not lay a finger on his attacker. Showing amazing self-restraint, he simply declared that he would no longer serve him as caravan leader. When Speke offered Bombay’s job to Nasib, the older of his two indispensable interpreters, he declined it. Instead, in Speke’s words, ‘the good old man made Bombay give in’.

Speke later rationalised the bludgeoning he had administered by saying that he could not have ‘degraded’ Bombay by allowing an inferior officer to strike him for disobeying a direct order from his leader. But really, Speke had behaved outrageously and knew it – especially since he respected Bombay more than any other man in his employ. ‘It was the first and last time I had ever occasion to lose my dignity by striking a blow with my own hands.’

2

It is some mitigation of the offence that virtually every other European explorer of Africa handed out thrashings from time to time in order to preserve a semblance of discipline – even Dr Livingstone. The endless vexations of African travel, and the hypersensitivity caused by repeated attacks of malaria, could sting the most patient of men into violent over-reaction.

While this row had been going on, N’yamgundu unexpectedly arrived and the caravan moved off soon afterwards. Two days later, several of the

kabaka

’s shaven-headed pages turned up carrying three sticks representing the three charms or medicines,

which Mutesa hoped the white man would give him. The first was a potion to free him from his dreams of a deceased relative; the second was a charm to improve his erections and his potency; and the third a charm to enable him to keep his subjects in awe of him. Though daunted by these outlandish requests, Speke’s confidence was boosted when a royal officer joined the caravan as it reached the northern shores of the lake and told Speke that ‘the king was in a nervous state of excitement, always asking after [him]’.

3

While the explorer’s principal interest still lay in locating the northern outlet of the Nyanza, he was also gripped by the drama of arriving at a unique feudal court and meeting a king whose ancestors had been monarchs since the fifteenth century.

As he came closer to the royal palace, Buganda itself began to charm him. ‘Up and down we went on again, through this wonderful country, surprisingly rich in grass, cultivation and trees.’ All the watercourses were bridged now with poles or palm trunks. Because the lake brought rain all the year round, the hills were as green as English downs, though larger, and their tops were grazed by long-horned cattle rather than sheep. Through banana plantations and woods, Speke caught tantalising glimpses of

his

shimmering lake.

On 18 February, the caravan was at last close to the

kabaka’s

palace. ‘It was a magnificent sight,’ enthused Speke in his journal. ‘A whole hill was covered with gigantic huts, such as I had never seen in Africa before.’ Indeed they were fifty-feet-tall conical structures, bound onto cane frames which were covered with tightly woven reeds. Speke had hoped to be summoned at once, but to his dismay was shown into a small and dirty hut to await the

kabaka

’s pleasure. N’yamgundu explained gently that a

levée

could not take place till the following day because it had started to rain.

Speke began the manuscript of his book

Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile

with a first sentence that would be deleted by his publisher:

Our motto being: ‘Evil to him who evils thinks,’ the reader of these pages must be prepared to see and understand the negroes of Africa in their natural, primitive, or naked state; a state in which our forefathers lived before the forced state of civilization subverted it.

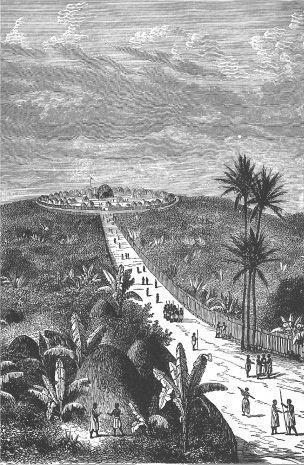

The road to the kabaka’s palace.

John Blackwood advised that this account of a ‘forced’ civilisation ‘subverting’ a more desirable and ‘natural’ way of life, should be replaced with a banal passage in which Speke could suggest that tribal faults and excesses might be viewed compassionately because Africans had been excluded from the Christian dispensation that gave Europeans their moral compass.

4

As will become apparent, the omitted sentence reflected his true feelings.

But to begin with, to gain respect, he planned to claim that he was a royal prince in his own country and therefore the

kabaka

’s social equal. Personal vanity in part explains this pretence, though practical considerations were also involved. To enter a self-contained world – which had remained, despite the arrival of Arab slave traders two decades before, almost exactly as it had been four centuries earlier – offered Speke, as this world’s first white visitor, an extraordinary opportunity. As the first of his race ever to be seen by the

kabaka

and his courtiers, Speke knew he would seem a marvel – and this would not only be personally gratifying, but would also make it easier for him to gain the

kabaka

’s support for his Nile mission. Or so he hoped. But the charm of his novelty might be lost were he to allow himself to be outshone or humiliated by the

kabaka.

So he gave much thought to the figure he ought to cut when marching from his humble hut to the royal enclosure where his audience was scheduled to take place the following day: 20 February 1862.

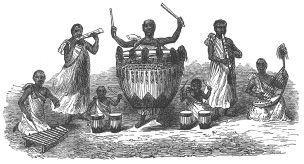

The Union Flag was carried in front of him by his

kirangozi,

while, just behind him, a twelve-man guard of honour, dressed in red flannel cloaks and carrying their arms sloped, followed. The rest of his people came next, each carrying a present. The little procession was led past huts ‘thatched as neatly as so many heads dressed by a London barber, and fenced all round with the common Uganda tiger-grass’. In one nearby court, musicians were playing on large nine-stringed harps, like the Nubian

tambira,

and on immense ceremonial drums. Within a

separate enclosure lived the

namasole,

or queen-dowager, with Mutesa’s three or four hundred wives, many of whom stood chatting as the little procession went by. In the next fenced court, Speke was presented to courtiers of high dignity: the

katikiro,

or prime minister, the

kamraviona

(properly

kamalabyonna)

or commander-in-chief; the

kangaawo

and the

ppookino

(‘Mr Pokino’ and ‘Colonel Congow’ to Speke), who were governors of provinces; as well as meeting the admiral-of-the-fleet, the first- and second-class executioners, the commissioner in charge of tombs, and the royal brewer. The

kabaka

’s cabinet of senior advisers, the

lukiiko,

‘wore neat bark cloaks resembling the best yellow corduroy cloth … and over that, a patchwork of small antelope skins, which were sewn together as well as any English glovers could have pieced them’.

Mutesa’s musicians.

Then, just when an audience with the

kabaka

seemed imminent, Speke was asked to sit on the ground and wait outside in the sun, as Arab traders were obliged to do. ‘I felt,’ recalled Speke, ‘that if I did not stand up for my social position at once, I should be treated with contempt … and thus lose the vantage ground of appearing rather as a prince than a trader.’ So he turned on his

heel and stalked off in the direction of his hut, while his men remained sitting on the ground, in a state of terror lest he be killed. But something very different happened. Several courtiers dashed after him, fell upon their knees, and implored him to return at once, since the king would not eat until he had seen him. But Speke turned his back on them and entered his hut as if mortally offended. Soon other courtiers arrived, humbly informing him that the king wished to be respectful and that Speke would be allowed to bring his own chair to the audience, ‘although such a seat was exclusively the attribute of the king’. Speke kept them waiting for his decision, while he smoked his pipe and drank a cup of coffee.