Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (26 page)

But though Mutesa became no less whimsically cruel, he pleased Speke and Grant two days after the latter’s arrival, by sending emissaries to Kamrasi to ask him once again to allow Baraka and Uledi to leave for Gani. But the explorers were warned by him that they themselves could not expect to go anywhere just yet. By now it was early June and Speke had been in Buganda more than three months.

24

As he was preparing for the next phase of his great journey, Méri came to see him several times, looking he thought

‘more beautiful than ever, and

[she went]

away sighing’

because wanting to be taken back. But Speke still believed that material considerations, rather than love, had inspired these visits.

25

At last, on 18 June, after Speke had enlisted the Queen Mother’s help, the

kabaka

agreed to let him and Grant travel eastward to the lake’s outlet and then north-west to Bunyoro. This permission was confirmed early in July, enabling them to leave on the 7th with a Baganda escort and sixty cows donated by the king. The king and Lubuga, ‘the favourite of his harem’, came to see them off, and Speke persuaded his men to

n’yanzig

for the many favours they had received. This was Speke’s own verb, which he had coined to describe the extravagant forms of obeisance lavished on Mutesa, such as kneeling and throwing out the hands, while repeating the words: ‘N’yanzig ai N’yanzig Mkahma’, and then floundering face-downwards on the earth like fishes out of water. His men must have done this vigorously, because Mutesa complimented them warmly, before taking one last glance at the white men, and then striding away, while Lubuga ‘waved her little hands and cried: “Bana! Bana!”‘

26

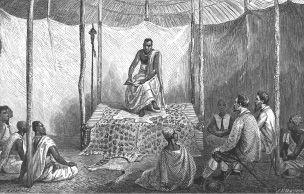

Royal wife led to execution.

ELEVEN

Nothing Could Surpass It!

Because Petherick could not be expected to wait indefinitely at Gani, ten days into his and Grant’s journey Speke was gripped by the absolute necessity of reaching the Nyanza’s outlet as soon as possible. After notching up the source, he would be free to hurry north to join hands with the Welshman, before travelling downriver with him to Gondokoro. Unfortunately, Grant’s ulcerated leg was still stopping him walking well, so the two friends agreed that it would be best if Speke and a small party of a dozen Wangwana and three or four Baganda were to march immediately to the outlet, while Grant travelled more slowly to Bunyoro with the expedition’s stores and the rest of the men. Once there, his task would be to gain Kamrasi’s consent for their passage through his kingdom to Gani.

1

In years to come, Speke’s critics would say that he selfishly reserved for himself what he confidently believed would turn out to be the discovery of the Nile’s source. But Grant would always deny this, saying he had been ‘positively unable to walk twenty miles a-day, through bogs and over rough ground … [and so had] yielded … to the necessity of parting’.

2

On no occasion would he ever blame Speke. Yet though Grant believed it would have been folly to risk letting his lameness delay their eagerly anticipated meeting with Petherick, three days after he and Speke had parted company, the normally sweet-natured Grant was seized by an uncharacteristic fit of rage. A goat-boy, who had briefly lost sight of his flock, was given twenty lashes on his orders – a shocking punishment for a minor offence.

3

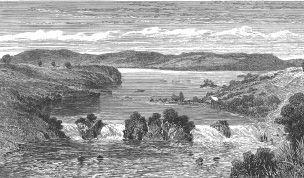

Speke had been detained by Mutesa for four and a half months, while being a mere fifty miles from the Nyanza’s principal outflow. This short journey proved trouble-free until his party

had to cross a three-mile-wide, mosquito-infested creek, which the cattle had to swim across with the men holding their tails. Then, on 21 July 1862, Speke wrote joyfully in his journal: ‘Here at last I stood on the brink of the Nile; most beautiful was the scene, nothing could surpass it!’ He had not

proved

that this really was the Nile, but on seeing the 600-yard river flowing between tall grassy banks, he felt more certain than ever that he had attained the object of his search. Everything about it struck him as beautiful. The valley was shaded here and there by tall trees, and the soft grass reminded him of English parkland. Hartebeest and antelope were browsing – while, occasionally, cloudy acacia and festoons of lilac convolvuli added something exotic to the scene. When Speke, in his excitement, suggested to Bombay that he and his men ought ‘to shave their heads and bathe in the holy river’, the African shrugged his shoulders. ‘We are contented with all the commonplaces of life,’ he remarked soberly, perhaps calling to mind exotic, shaven-headed holy men in India.

4

The name of this place was Urondogani, and because it was a few miles downstream from the Nyanza, Speke tried to hire boatmen to take him and his men southwards, upstream to the precise point at which Nyanza and river met – for there, he had decided, would be the source itself. But the locals refused all help, and so he was obliged to ‘plod through huge grasses and jungle’ for three more days to the place called by the Baganda, ‘The Stones’.

Speke admitted in his journal that ‘the scene was not exactly what I [had] expected; for the broad surface of the lake was shut out from view by a spur of hill, and the falls, about 12 feet deep and 400 to 500 feet broad, were broken by rocks’. Nevertheless, despite the unspectacular nature of the place, he stared for several hours, mesmerised by the water rushing from the lake between the rocky islets and sweeping over the long ledge of rock into the river, as ‘thousands of passenger-fish [barbel] leapt at the falls with all their might’. He had no doubt that this was the very point at which the lake gave birth to ‘old father Nile’. Bewitched by the place, he mused that he would only need ‘a wife and

family, garden and yacht, rifle and rod, to make [him] happy here for life’. He also thought it the perfect location for a Christian mission. He named ‘The Stones’ the Ripon Falls, after the first Marquess of Ripon, President of the RGS and later viceroy of India. The stretch of water into which the lake at first funnelled, he called the Napoleon Channel out of respect for the Emperor Napoleon III. Unlike the RGS, which had only honoured Burton with its Patron’s Gold Medal, the French Geographical Society had presented Speke with its Medaille d’Or for his discovery of the Nyanza, making him a Francophile for life.

5

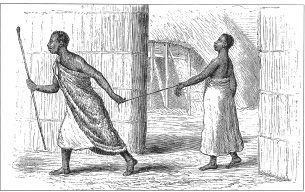

The Ripon Falls.

Speke dallied three days at ‘the source’, watching the fishermen coming out in boats and stationing themselves on the islets with rods. Hippopotami and crocodiles lay sleepily on the water and cattle came down to drink in the evening. The explorer finally tore himself away and set out downstream into Bunyoro, with his fifteen men in five flimsy boats, little better than rafts. His plans were ruined by Kasoro, the man deputed by Mutesa to guide him, but who now led a raid against some Wanyoro traders in canoes. Henceforth, Speke expected hostility

en route,

and got it the same day, when ‘an enormous canoe, full of well-dressed

and well-armed men’ came up behind his rafts and then kept pace with them. The banks on each side grew higher and were soon lined with men thrusting their spears in his direction. The crew of the pursuing canoe paddled faster and swung their vessel across the bows of Speke’s little craft. Even now, Speke was in denial about the gravity of his situation. ‘I could not believe them to be serious … and stood up in the boat to show myself, hat in hand. I said I was an Englishman going to Kamrasi’s, and did all I could, but without creating the slightest impression.’

Other canoes, full of armed men, now slid out from the rushes that lined the banks, compelling Speke to order all his boats to huddle together, so that no vessel could be picked off. But several of his captains preferred to go their own way, and one of their boats was promptly caught with grappling hooks, forcing its crew to choose between using their firearms or being boarded and stabbed to death. From across the river, Speke heard his men fire three shots, and saw two Wanyoro warriors fall, one killed outright. Fearing he would now be ambushed if he continued downstream, Speke decided to travel overland to Bunyoro. It comforted him to believe that Grant was already at Kamrasi’s capital, and would have established friendly relations.

However, on 16 August, Speke was shocked to hear that Kamrasi had not allowed Grant to enter his country, and a mere five days after that, he stumbled on his companion’s camp, close to the border. Soon afterwards, these two avid hunters came upon a large herd of elephants that had never heard a shot fired. The explorers’ joy was short-lived. When Grant hit an old female, she merely ‘rushed in amongst some others, who with tails erect commenced screeching and trumpeting, dreadfully alarmed, not knowing what was taking place’. Both men were so upset by this spectacle that they stopped firing. ‘I gave up,’ recorded Speke, ‘because I never could separate the ones I had wounded from the rest, and thought it cruel to go on damaging more.’

6

Now that Kamrasi had forbidden them to enter his kingdom, the explorers faced a grim dilemma. Should they nevertheless risk crossing Bunyoro uninvited in order to reach Gani,

where they believed Petherick was still waiting with boats and supplies, or should they give up the idea of following the river downstream and try instead to persuade Mutesa to give them the men to travel through Masailand to Zanzibar? When they were on the point of deciding, six Wanyoro guides arrived with the wonderful news that Kamrasi would see the white men after all.

7

Shortly after this, 150 of Kamrasi’s warriors arrived to escort them – a sight which made Speke’s Baganda guides flee rather than risk being killed by their traditional enemy. The Baganda took with them twenty-eight panic-stricken Wangwana, leaving Speke and Grant with a mere twenty followers – far too few to guarantee them a safe journey north to Gondokoro, unless Petherick could be located and soon.

8

Though confident that he had found the Nile’s source, Speke knew he would be treated sceptically unless he could describe the course of the river on its way to Gondokoro. Once again an African monarch seemed likely to determine whether his mission would be satisfactorily completed.

Kamrasi, the monarch in question, feared that some super-naturally inspired misfortune might befall him if he admitted the white men, though he had no desire to deprive himself of the gifts they might shower on him. So he kept them at arms’ length, housed in huts ‘in a long field of grass, as high as the neck, and half under water’. This waterlogged wedge of land was encircled by the crocodile-filled river and one of its effluents, the Kafu, thus obliging the explorers to embark in a canoe when making their long-delayed first visit to Kamrasi’s audience-hut.

Their reception by the

omukama

(the traditional title of all kings of Bunyoro) took place on 9 September 1862, after a wait of nine days during which Kamrasi had weighed up the risks and benefits involved in seeing them. He greeted them coldly, giving no indication whether they would be allowed to follow the river downstream and visit Gani. In contrast to Mutesa’s excitement when examining his presents, Kamrasi hardly glanced at his. He only seemed mildly interested in a double-barrelled gun and a gold chronometer watch, which he had noticed Speke take from

his pocket. The

omukama

dressed more plainly than Mutesa, in local bark-cloth rather than in silk or calico. Although dourer than the

kabaka,

he turned out to be more humane, only executing murderers and letting off minor criminals with a warning.