Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (59 page)

Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Ironically, the Sudan Political Service, Britain’s executive in the Sudan, was the most highly educated ruling èlite in the history of empire. Sudan has memorably been said to have been ‘a land of Blacks ruled by Blues’. Indeed, one in four of its officials over fifty years had won a Blue for sporting prowess at Oxford or

Cambridge, and ten per cent had gained a first-class degree at one or other of those universities. Never more than 125 strong at any given time, they ruled effectively (at least in the north), abolishing slavery, and promoting agriculture, public health and education in Africa’s largest colony.

10

Most of these intelligent young men were Arabic speakers who found the northerners, whom they met on a daily basis in Khartoum, eager for education and economic development. But the southern Sudanese appeared in a very different light, striking the most senior civil servant in the country as relics from ‘the Serbonian bog into which they had drifted, or been pushed … [guaranteeing that] all the lowest racial elements surviving north of the equator’ were to be found in southern Sudan.

11

Sir Harold MacMichael, who wrote those words, was the top civil servant in the Sudan. With his Cambridge first in classics, his fencing Blue and his titled mother, he loved social life in Khartoum, and postponed a visit to ‘the Serbonian bog’ for seven years after his appointment. Eventually in 1927 he took the plunge, and his few days down south shocked him to the core. Depending upon whether it was the wet season or the dry, the whole southern region was either a gigantic swamp, or an endless mud-baked plain. The Nilotic peoples who lived in this hot and treeless wilderness – the Dinka, Nuer and the Annuak – were tall, physically graceful, proud, and absolutely determined to preserve their way of life in their remote and inaccessible habitat. MacMichael, from behind the anti-mosquito wire-netting which protected the passenger deck of his comfortable steamer, feared that it would be impossible to persuade such people to embrace ‘civilisation’ as the northern Arabs appeared to wish to do. In Equatoria there was no ‘native administration’ to build on, and little chance of initiating a system of agricultural exports that would pay for the region’s development. He therefore refused to commit his administration to the expense of building roads and improving water access. Such a project ought to have been his number one priority, but instead a policy of benign (in reality malign) neglect was dreamed up. It would insultingly be known

as ‘care and maintenance’.

12

Nor was ‘Macmic’, as MacMichael was affectionately known, going to send any of his gilded young Arabists from the Sudan Political Service to sweat, and possibly be speared to death, in the mosquito-infested south.

The men chosen to ‘care’ for the south were described sardonically by the Khartoum èlite as ‘the Bog Barons’. Mainly former army officers, they treated the inhabitants of their administrative districts with a mixture of despotic arrogance and genuine affection. They took great risks in their efforts to get the Dinka and Nuer to accept the Khartoum government, and some, such as Captain V. H. Fergusson, were murdered – in his case by a Nuer who had thought, thanks to a confusion over words, that ‘Fergie’ had come to his village to castrate him. This murder, like all others, would unleash ferocious British punitive expeditions.

13

But Major Mervyn J. Wheatley, who was a future mayor and MP, refused to crush the Dinka by waging war and bravely set about persuading them to make peace by making personal contact. Jack Herbert Driberg was not a soldier, but he exemplified the best qualities of the Bog Barons: disdainful of Khartoum officials, this poet, boxer and one-time music critic loved the Didinga people, fought their corner vigorously, and in 1930 published a book about them:

People of the Small Arrow.

Eventually he was sacked for allowing his partisanship to lead him physically to attack the Didinga’s enemies. Some barons were extremely eccentric, like the officer who dressed the crew of his private Nile steamer in jerseys embroidered with Arabic words meaning: ‘I am oppressed.’ Inevitably in their isolated situation a number of barons took African mistresses.

14

For all the Bog Barons’ success in winning the trust of the indigenous peoples of the south, much more was needed if their charges were ever to participate as equal partners in an independent Sudan. Above all, a better understanding was urgently required between north and south, especially in matters of education, language and culture. Yet, from as early as 1898, Sir Reginald Wingate had encouraged British missionaries to go out to Equatoria to convert the locals and teach them English. Wingate wanted to

turn southern Sudan into a Christian bulwark that would protect Uganda and Kenya from the southward spread of Islam.

In 1910, Wingate went further and sanctioned the formation of a separate Equatorial Corps manned by non-Muslim Africans for military service in the south. Within seven years all northern troops had been withdrawn from the Bahr el-Ghazal area. The teaching of English and the exclusion of Arabic from southern schools had become official policy from as early as 1904, but, as Wingate had advised, it was to be implemented ‘without any fuss and without putting the dots on the

i

s too prominently’. So English became the

lingua franca

in the south almost by stealth, only becoming official in 1930.

15

It might be thought that Wingate and his successors had been secretly planning to unite southern Sudan with Uganda. But no direct evidence that this was really their intention exists. Meanness does not entirely account for low spending on education in the south. There was a genuine fear among the Bog Barons that education

per se

might undermine a rich traditional way of life without putting anything of value in its place. ‘It is essential,’ said a speaker at an educational conference in Juba in 1933, ‘that we who are concerned with education should keep clearly in mind that education is a preparation and training for life in a tribal community which still contains social virtues which we in our individualistic western civilization are losing or have lost.’

16

It would be eleven years before the Governor-General’s council finally abandoned their Arcadian view of the south. In 1944, it was reluctantly accepted that Britain had less than twenty years (in truth a dozen) in which to prepare the country for independence. The mistakes of the past were to prove impossible to put right in the midst of a world war in which Britain was fighting for survival. But the language of the north was finally introduced into southern secondary schools in 1948 in a last-ditch attempt to prevent the southern Sudanese from being gravely disadvantaged in a country that would soon be ruled by Arabic-speakers.

17

But perhaps the south could still be saved from subordination and second-class citizenship if a brave political decision could be

made. In 1943, C. H. L. Skeet, the Governor of Equatoria, still hoped that the British government would keep all options open:

The political future of the Southern Sudan cannot yet be determined, but whatever it may be, we should work to a scheme of self-government which would fit in with an ultimate attachment of the Southern peoples southwards or northwards [i.e. connected with Sudan or with Uganda] … The policy that is being adopted makes political adhesion to the North improbable from

the Southern Point of View

.

18

A year later, the Governor-General, Sir Douglas Newbold, tried to persuade the Sudanese nationalists, who would soon be ruling Sudan, to leave the south to the British, but he was angrily rebuffed. So, in April 1944, the Governor-General’s council at last decided to embark on a regime of ‘intensive economic and educational development in southern Sudan’. Since no other money was available, this would have to be paid for with northern funds. This hard fact ended ‘any serious prospect of the separation of the two regions’. Of course no ‘intensive’ programme was going to make up for thirty years of neglect and the south was now doomed to be subservient after independence.

19

Nor was there any practical possibility of attaching the Nilotic peoples of southern Sudan to Uganda with its Bantu-dominated south. British officials and the Bagandan èlite would have rejected the idea out of hand.

In reality the only way to have avoided future tragedy would have been to preserve Equatoria as a nation in its own right. Yet to attempt to redraw the 1913 border in the 1940s would probably have provoked the northern Sudanese to armed resistance. And in any case it is doubtful whether Uganda’s mission-educated northerners would ever have consented to becoming part of southern Sudan – a less developed country than the one to which they were currently attached.

Yet Sudan’s south was not going to accept absorption and control by the Muslim north. The rebellion that had been brewing for two decades erupted in southern Sudan on 18 August 1955, five months before independence, when the Equatorial Corps mutinied against northern Sudanese officers who had

just replaced that corps’ popular British commanders. The long and tragic Sudanese civil war had started. It would last, with an interval of eleven years, until 2005, by which time four decades of fighting would have cost two million lives.

20

Of course the roll call of people individually and collectively responsible for this terrible disaster was long. Sir Reginald Wingate, Sir Harold MacMichael and successive British Colonial Secretaries must bear a share of the blame for what happened by their failure to plan the development of the south and to foresee the suffering that would ensue if the south was still part of Sudan when independence came. Nor should Sir Samuel Baker escape blame for eagerly agreeing to extend Egyptian power to the borders of the future Uganda and beyond, thus lumping together, for the very first time, Arab Sudan and African Equatoria in a union that was destined to stick. In fairness to him, Gordon and Emin Pasha followed his lead and consolidated the territory he had claimed.

The northern Sudanese were also culpable, some of them criminally so. Even at the eleventh hour, before the mutiny, Sudan’s first government-elect could have heeded the south’s demand for southerners to be appointed to senior positions in the administration and the police. Yet, instead of demonstrating the unity of the nation by making appointments that would have made the southerners feel included, Ismail al-Azhari and his cabinet insulted them by offering beggarly junior appointments instead of the governorships and deputy governorships that had been asked for. This fault of deliberately ignoring a federal solution in favour of a military one would be repeated by Jafar Numeiri, Sadiq al-Mahdi, and most of all by the fundamentalists Hassan al-Turabi and Omar al-Bashir.

21

In the end, despite the fact that 90 per cent of the members of Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood had been British- or American-educated, and despite the existence of multi-party politics, the religious fundamentalists engineered a coup and took over in the late 1980s after losing at the ballot box in 1986.

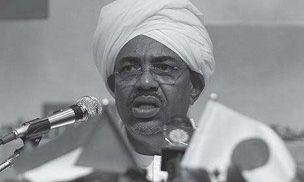

Just over a century after General Gordon had been killed on the steps of his palace, and thirty years after independence, a Sudanese general – Omar al-Bashir, now president of Sudan -addressed a rally in Khartoum, holding a Koran in one hand and a Kalashnikov in the other. It was as if the religious fundamentalism of the Mahdi, which had flowed underground for the tranquil duration of British rule, had simply re-emerged a century later. Under Bashir’s Islamic dictatorship the war against the south became a

jihad

and the Sudanese government actively encouraged militias to go on slave raids there, and in Darfur. Bashir and his elderly mentor, the Islamic scholar and Sorbonne-educated lawyer, Hassan al-Turabi, welcomed to their country groups interested in joining the ‘war on America’. Among those choosing Sudan as a base was the Saudi construction magnate, Osama bin Laden. His choice of location seemed to influence the language he would use against the Americans, since it bore a striking resemblance to the Mahdi’s pronouncements against the British and the Egyptians a century earlier. Terrorist attacks mounted from Sudan included an attempt to kill the former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, and bombings in Israel, Kenya and Tanzania. Whatever the faults and omissions of the British administrators, they will forever be dwarfed by the crimes of their Sudanese successors.

22

Omar al-Bashir.

Now, in the eleventh year of the twenty-first century, 99 per cent of voters in southern Sudan have opted for secession from the north, as they were entitled to do under the terms of the 2005 peace treaty brokered by America and Britain. So what should have happened before Sudan’s independence in 1956 has happened fifty-five years after it. The remedy, however, will be incomplete since the southern half of Equatoria will remain within Uganda. Nor is there any certainty that northern Sudan will respect the south’s independent statehood in the years to come.