Read Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure Online

Authors: Tim Jeal

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #History

Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure (28 page)

But it would not be until six years later that Baker saw how to use Speke and muscle in on the search for the Nile’s source. This was by writing to John Petherick and offering to join him on his mission to ‘succour’ Speke and Grant on the last leg of the journey they had embarked upon in the spring of 1860. Baker secretly hoped that if the pair were dead, or had been detained somewhere far to the south, he might even manage to beat them to the source. But the RGS had vetoed his joining Petherick’s expedition, and had instead suggested that he explore the Ethiopian tributaries of the Blue Nile to determine the contribution these waters made to the annual flood in Egypt. So, between March 1861 and June 1862, Baker, who was rich enough to need no patronage, had

explored the Ethiopian Highlands, discovering in due course that the torrential summer rains which fell there each year accounted almost wholly for the life-giving floodwaters that poured into the White Nile between June and September, irrigating the entire valley of the lower river. But this important scientific finding had in no way appeased Baker’s longing to make the most glamorous discovery of all.

Just before setting out to map the Blue Nile and the Atbara, he had been asked by the Egyptian governor of Berber where he was going, and had replied without any attempt at subterfuge: ‘To the source of the White Nile’. Baker had been accompanied then – and still was, on arrival at Gondokoro – by a slender white woman, dressed like himself in trousers, gaiters and a masculine shirt. Observing her youth and apparent fragility, the governor had urged the Englishman to leave her behind, since a journey up the Nile ‘would kill even the strongest man’. But Baker, who loved to have his mistress with him, had no intention of heeding such advice.

2

The way in which the nineteen-year-old came to be with him in the first place was a story in itself. Baker had purchased his ‘Florence’, as he called her, two years earlier at an auction of white slaves in the town of Vidin in Turkish-administered Bulgaria. Born Barbara Maria von Sass in Transylvania, then part of Hungary, Florence’s parents had been killed in the 1848 Hungarian uprising, and she had later been raised by a business-minded Armenian, who expected to get a good price for her in due course. Whether desire or pity had bulked larger in Baker’s decision to bid for the girl against so many prosperous Turks cannot be known, but he had soon fallen in love with her, subsequently taking a job in Romania as managing director of the Danube and Black Sea Railway solely in order to remain with her. Not that this was suspected by any of his four teenage daughters, who had been cared for in England, after their mother’s premature death, by an unmarried sister and must have found their affluent father’s decision to work in faraway Romania inexplicable as well as hurtful. But as a respectable

widower, Samuel Baker had not even considered bringing back to England a mistress twenty years his junior and little older than his own children.

Of course, taking her to Africa, where she would meet nobody he knew (with the possible exception of Speke) had been a different matter. On the point of sailing for Alexandria in February 1861, Baker had briefly debated whether it would be safe for her to accompany him but had been unable to endure the thought of spending night after night in his tent without her. Now in March 1863 in Gondokoro – although planning disingenuously to tell Speke that he had come to Africa only in order to help him and Grant come safely home – he still had not decided how to introduce Florence.

3

But as he approached the exhausted travellers, he was able to postpone this delicate decision a little longer, since Florence had stayed aboard their boat that morning, after feeling unwell on waking.

As Baker’s fellow countrymen came ever closer along the riverbank, walking beside a long line of moored vessels, he was overwhelmed with patriotic emotion. Speke with his fair hair and tawny beard was ‘the more worn of the two … excessively lean, but in reality in tough condition … Grant was in honourable rags; his bare knees protruding through the remnants of trousers that were an exhibition of rough industry in tailor’s work’. Yet though ‘tired and feverish … both men had a fire in the eye that showed the spirit that had led them through’.

4

Humbled by the length of their journey from the southern to the northern hemisphere, and by their courage, Baker called out: ‘Hurrah for Old England!’ as he hurried up to them; but even as he embraced his compatriots, he felt chagrined that he had not managed to rescue them from ‘some terrible fix’ many miles further to the south of here. Gondokoro seemed suddenly rather tame, although Baker had spent lavishly to get thus far. So when Speke and Grant informed him that they had visited the Nile at enough points on its course to ensure that it originated in the Nyanza, he assumed that his own expedition was over, and felt too crestfallen to wonder if they had really proved their case.

5

But, making the best of things, he told the explorers brightly that he had come ‘expressly to look after [them]’ by placing at their disposal a mass of trade goods, over forty men, camels, donkeys, a

dahabiya

(a ninety-foot Nile pleasure-boat) and two smaller vessels. Given the non-appearance of John Petherick, Grant and Speke were touched that this Good Samaritan was offering to do so much for them out of his own pocket, without having received a penny of public money. Baker now told them that Petherick, by contrast, had received almost £1,000 by public subscription raised so that he could ‘succour’ them.

6

Although another

dahabiya,

the

Kathleen,

and three cargo boats, had been sent to Gondokoro by Petherick and were currently moored there – and although Speke and Grant would shortly lodge their servants and their stores in the

Kathleen

– they accepted Baker’s invitation to come and live with him on his

dahabiya.

7

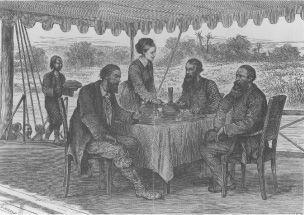

On his well-appointed boat, he seated them under an awning and called for refreshments. For months, the travellers had tasted nothing even as basic as tea, sugar and bread. Not surprisingly, they eagerly consumed whatever was set before them. When a pretty young woman came on deck, Speke became flustered. He had heard he seemed to remember, that Baker’s wife had died a few years previously. So, without thinking, he blurted out: ‘I thought your wife was dead.’ After an awkward silence, Baker agreed that his wife was indeed dead, and declared that Florence was his

‘chère amie’.

8

Speke’s gaffe, though embarrassing to everyone, including Florence who was feverish at the time, did no harm to the esteem in which Baker was already held by the new arrivals, who considered themselves men of the world. They now described their journey, mentioning, along with much geographical information, the chiefs and rulers met on their way. But this was a mere curtain-raiser to the astonishingly generous suggestion that followed.

Grant and Speke entertained by Florence and Baker on his

dahabiya

.

Suddenly, Speke proposed to Baker that he, rather than the absent Petherick, should be the one to try to ‘discover’ the Luta N’zige lake, which due to Kamrasi’s prohibitions he and Grant had been unable to reach. This had been a severe disappointment, he explained, since they both believed that the Nile flowed into the Luta N’zige, and then out of it again to the north. This was guesswork of course, since neither had followed the river to the lake, nor seen it flow out.

Although Speke and his companion clearly thought of the Luta N’zige as at best a subsidiary reservoir of the Nile, Baker – ever the optimist – told himself it might prove ‘a second source of the Nile’. Earlier, he had turned to Speke with a self-deprecating smile and asked: ‘Does not one leaf of the laurel remain for me?’ He was overjoyed to discover that a substantial sprig might be his for the taking, if he agreed to brave a journey bristling with dangers (although no more than 250 miles there and back). In answer to the question whether he was prepared to attempt to reach the lake, Baker handed his diary to Speke who opened it and then wrote three pages of directions, including invaluable advice about guides and interpreters.

9

The only subject upon which Speke and Baker differed was whether Florence ought to go to the lake. As Grant recalled: ‘In talking over the matter with Speke, I said: “What a shame to

have so delicate a creature with him.”‘ Speke agreed and even told Baker to his face that he ought to marry Florence on his return to England.

10

But what upset Speke much more at this time than Florence’s predicament was the supposed treachery of the once well-liked Welshman, John Petherick.

Speke and Grant knew that the Welshman was an unsalaried, honorary consul who had long been obliged to trade in ivory for a living, but because he had received subscription money they were upset to learn that he was trading far to the west of Gondokoro, rather than coming to greet them. In the consul’s RGS instructions, he had been told that the money had been subscribed by the public specifically to ‘enable [him] to remain two years to the southward of Gondokoro … rendering assistance to the expedition under Captains Grant and Speke’. If the explorers were not at Gondokoro on his arrival, Petherick had been instructed to leave boats there and then head south in person for the Nyanza.

11

Yet though Petherick’s

wakil

had indeed left three boats at Gondokoro, Petherick himself would never set foot there until his arrival five days after Speke and Grant, nor had he or his

wakil

taken a single step further south towards the Nyanza.

12

Baker had been corresponding with Petherick and could (had he so desired) have explained that the consul had been delayed by illness and other misfortunes, but Baker chose to say nothing. Since Speke’s public attacks on Petherick would later prove infinitely more damaging to

his

reputation than to Petherick’s, it is important to determine whether Baker was also to blame for what happened.

13

A daily visitor to Samuel Baker’s

dahabiya

in which Baker himself, Florence and the English explorers were all staying, was a Circassian slave trader, Khursid Agha.

14

Baker was friendly with the man, despite the fact that Petherick had written telling him that Khursid had recently made a great

razzia

(slave raid) on the Dinka, along with De Bono’s nephew, Amabile, and Petherick’s own

wakil,

Abdel Majid. Baker also knew that Petherick, as honorary British consul in Khartoum, had attempted to enforce the

khedive’s

law against slaving by arresting both Amabile

and Majid for capturing hundreds of slaves, including eighteen children.

15

Inevitably Khursid hated Petherick for arresting his friends and for handing them over to the Egyptian authorities in Khartoum, so it was probably he who mentioned to Speke, aboard the

dahabiya,

that Petherick had himself been accused of slave trading by some European traders and diplomats in Khartoum. On returning to England, Speke would use this information to make a thinly veiled attack on Petherick for slave trading.

16

Samuel Baker could easily have saved Speke from making this foolish allegation by admitting that he himself believed Petherick innocent.

17

But Baker wanted to replace Consul Petherick as the man to ‘succour’ the explorers, and he also hoped to ensure that when Petherick eventually arrived, Speke would not feel inclined to let the Welshman share in the glory of finding the Luta N’zige.

18

The less Speke liked Petherick, the better things would be for Baker – or so Baker appears to have calculated.

Despite being six years older than Speke and Grant, Baker got on well with both. All three had much in common in respect of background and interests, which included a shared passion for shooting, for exploration, and (with Grant at least) for painting in water colour.

19

So when Petherick, the former mining engineer and his wife, Katherine, finally appeared on 20 February, the cosy trio of English gentlemen on the

dahabiya

closed ranks against the newcomers. In his published journal, Speke claimed that he had managed to be civil to the consul and his wife soon after their arrival. ‘Though naturally I felt much annoyed at Petherick – for I had hurried away from Uganda, and separated from Grant at Kari, solely to keep faith with him – I did not wish to break friendship, but dined and conversed with him.’ In fact, Speke later admitted that he had spoken out in anger.

20