Fail Up (2 page)

In other words, he failed up.

Interestingly, it was my love for Martin that led me to Malcolm. Throughout history, pitting Black leaders against one another has been an effective maneuver. As a youngster, I wanted to know more about this guy Malcolm who was declared by the media and the man on the street to be the frightening antithesis of Martin. When I read the

Autobiography of

Malcolm X

, I truly understood the worth and value of Malcolm's life and legacy. What's more, I discovered a connection with Malcolm that I did not find in Martin's life story.

The two men couldn't have started their lives in more diametrically different places. I really couldn't relate to Martin's upbringing because he was raised in a bourgeois, middle-class Black family. Malcolm's hardscrabble life, on the other hand, reflected my Mississippi and Indiana upbringing. His struggles with poverty, race, low self-esteem, family chaos, and trouble at school resonated with my life story at the time.

Not only did I grow to have an abiding love for Martin and Malcolm, I also wanted to emulate their powerful examples of courage, faith, resilience, and dedication to uplift our people.

These two men, my incontestable heroes, were both assassinated at the age of 39. My admiration and identification were so strong that I was convinced that I, too, would not live past the age of 39. Not that I was remotely putting myself on these icons' pedestals, no way. But sometimes, when the realities of your world become too harsh, an unconscious fatalism can overtake you and make you seek refuge in someone else's story as a way to make sense of your own.

But it wasn't just the far too brief lives of Martin and Malcolm that persuaded me that I would die young. There was another, perhaps even more influential factor that made the idea of my early demise seem an inevitable, stark reality.

Anybody familiar with the Pentecostal churchâespecially old-school Pentecostal church teachingsâunderstands the ramifications of “hell and damnation” preached incessantly. “The world is going to end,” “He's coming soon and if you're not living right, you're going to hell,” “Armageddon is upon usâget right with God!” These were the messages that permeated the foundation of my childhood.

The combination of these thoughtsâthat my heroes were dead at the age of 39 and that the world's demise was imminentâhad me living on the edge. I was scared to die and haunted by feelings that I would not have enough time to make the kind of societal contribution that I wanted to make. This underlying sense of urgency drove me to work hard, work fast, and succeed. Now!

Sure enough, as you will read in this book, I did work hard and I was blessed beyond measure.

By the age of 38, I had accomplished much: writing popular books, hosting national television and radio programs, being featured on the covers of magazines and newspapers, and so much more. I was even financially secure with a comfortable net worth.

Then I turned 39.

The fear that I would not make it to 40 began to overtake me. And what was worse is that I felt like I was a failure. Even though I was just one personâand a cracked vessel at thatâI knew I hadn't done enough. For all that I had tried to accomplish, the problems in my community and my country and the world seemed so intractable. Poverty. Sickness. Crime. Racism. Environmental abuse. Child neglect. Educational inequities. War.

The night I turned 40, I was alone in a hotel room in Houston and had a major panic attack. The details of that night are so traumatic, forgive me for not wanting to relive them here.

But shortly thereafter, I did share my nightmare in Houston with my abiding friend, Dr. Cornel West, over dinner.

Doc and I had talked many times before about my fear of dying young, so he understood the reason for the episode. But there was one part of my story he couldn't quite rationalize.

“How, at 40 years old, could you think that you are a failure?” he asked.

After I answered his question, Doc began to share with me his unique take on the matter of life and death:

“Tavis, the older I get, the more I think that there really is no such thing as penultimate success. I believe that every one of us essentially dies a failure.”

Huh? Doc knew I was having trouble with his reasoning, so he pressed on:

“If one dies at 39, like Martin and Malcolm, or if one lives to be 139, you're not going to get it all done. There are going to be ideas you will never develop, projects you will never complete, conversations you will never have, people you will never meet, places you will never go, relationships you will never establish, forgiveness you will never receive, and books and speeches you will never write or deliver. We all die incomplete.”

So, Doc added, “the central question becomes: How good is your failure?” With that, he dropped the Beckett quote on me:

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter.

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Doc was right. Ultimately, life is about failing better. Every day you wake up, you get another chance to get it right, to come up from failure, to fail up.

In working with young people through our foundation, I no longer use the phrase

just do your best.

If what you give the world is your best, then how do you get better?

The conversation with Dr. West freed me because it gave me a different perspective on the true meaning and the real value of failure.

Beckett's quote has become one of my favorites. I share it with young or old, Black or white, whenever I have the opportunity. Motivational speaker Les Brown says, “When life knocks you down, try to land on your back. Because if you can look up, you can get up.”

Failure is an inevitable part of the human journey.

Fail

up

is the trampoline needed when you're down. When you take the time to learn your lessons, when you use those lessons as stepping-stones to climb even higher than you were before, you transcend failureâyou “fail up.”

As I celebrate 20 years as a broadcaster, now is the time to show my scars. I hope the 20 lessons presented in the following chapters will offer you a new way to think about your failures.

I'm a witness. You

can

fail up.

“When you are as great as I am

it's hard to be humble.”

âMUHAMMAD ALI

O

ne of my fondest adolescent memories was sitting in front of my family's black-andwhite, floor-model television with my Dad watching the fights broadcast on ABC Sports hosted by Howard Cosell. We watched one heavyweight in particularâMuhammad Ali. My Dad, like a whole lot of Black men back then, was a huge Ali fan. Eventually, his hero became my hero, and I loved watching those fights with him.

There was something about Ali that attracted me even more than his ability to dance, shuffle, and knock you out. An articulate and braggadocious talker, Ali predicted the outcome of his fights in rhyme: “You're going down in the third round!” Mostly, I loved Ali because he wasn't afraid of white folk. Be it defending his religion or his stance against the Vietnam War, he used his mind and his mouth to whip opponents inside and outside the ring.

Imagine Ali's impact on a Black child who constantly felt like an outsider. The only time I saw Black folk, other than my family, was when we attended an all-Black church some 30 miles away from our home. As I detailed in my memoir,

What

I Know For Sure

, I was raised in Indiana, lived in an all-white trailer park, and attended a virtually all-white school.

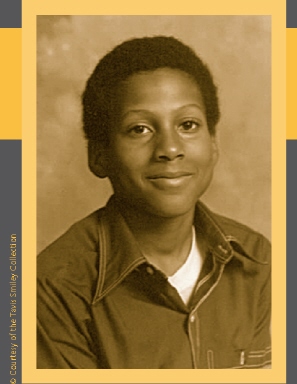

There were ten kids and three adults living in a doublewide trailer. Money was tighter than tight. It wasn't unusual for the Smiley children to wear hand-me-down clothes or shoes with cardboard tucked inside the soles to cover holes. Neighborhood white kids didn't hesitate to point out that my family was poorer, bigger, and blacker than theirs.

I developed a deep sense of class- and race-based inferiority.

But that was before I came under the spell of Muhammad Ali.

I convinced myself that Ali and I shared similar traits. I was smarter than most of my classmates, I had an excellent memory, and I could out-talk anybody. If Ali could challenge white people with his mind and his mouth, so could I.

I began to check classmates with my quicknessâcorrecting them if they were wrong, arguing with them if they thought they were right, and placing bets to prove that I could articulate faster, more eloquently, and more accurately than they could.

Substituting feelings of inferiority with intellectual superiority helped me verbally knock out contenders left and right. And, for awhile, it felt great. Problem was, during my Ali phase, I started getting into physical fights and trouble with teachers at school. The worst partânobody liked me.

Because of my mind and mouth, I could make no friends.

The Arrogance of Youth

If you study Ali's life, particularly when he was younger, you'll understand why I was having trouble making friends in school. Although I wasn't using derogatory put-downs, my desire to verbally knock out my challengers and to impress with lightning-fast wit was perceived as arrogance. My peers had no idea I was fighting an inner battle against race and poverty-based low self-esteem. They didn't know I was trying to prove that I was “the greatest” orator for my own survival.

As you progress through this book, you'll note some important lessons I learned due to my ill-timed or unwise use of words. But, back in the mid-1970s, I was too caught up in pubescent adulation of Ali's razzle-dazzle to give much thought to the damage his poetic slings and barbs might have wrought on his opponents.

I was born seven months after Ali defeated ex-con and knockout expert Sonny Liston in 1964. I was just a baby when, after the first Liston fight, Ali announced to the world that he had become a member of the Nation of Islam and had changed his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali. Years later, at the age of 11, I was too young to really comprehend the injustices or ramifications of the Vietnam War.

Yet somehow, these events were all part of the magical lore of the quick-footed boxer my father adored.

Through his stories, I learned that Ali had been exiled from boxing after refusing to fight in the war. My father's excitement was contagious when Ali came back to the ring in 1970. Together, we celebrated his triumphs over Jerry Quarry, Oscar Bonavena, Ken Norton, and Joe Frazier in the early 1970s. My father and I were side by side when Ali defied all odds and floored the one-punch wonder George Foreman in 1974. And, of course, we had to watch when two of the best fighters of all timeâAli and Frazierâfought for the third time. To this day, the “Thrilla in Manila” fight stands as one of the greatest heavyweight bouts in boxing history.

It's been reported that 21 years after that infamous match, Joe Frazier still bore the scars of Ali's verbal abuse.

“Before we fought, the words hurt more than the punches,” Frazier told author Thomas Hauser for Ali's biography,

Muhammad

Ali: His Life and Times

.

Frazierâa hard-hitting, take-no-prisoners Philadelphia brawler born in segregated Beaufort, South Carolinaâdidn't deserve the dishonor heaped on him by Ali:

“Frazier is so ugly that he should donate his face to the U.S. Bureau of Wildlife.”

“It's gonna be a thrilla, and a chilla, and a killa, when I get the Gorilla in Manila.”

That last riff was emphasized with a tiny gorilla doll Ali sometimes carried with him that was supposed to represent Frazier. Although many whites hoped Frazier would give Ali his comeuppance, “Smokin' Joe” did not fit the criteria of the white man's champion. Thus Ali's taunts were like unnecessary, below-the-belt blows. Frazier by no means deserved to be called a “gorilla” or an “Uncle Tom.”

Time seems to have given Frazier the perspective to move past the pain Ali's words caused. “You have to throw that stick out of the window,” he told

Sports Illustrated

writer Matthew Syed in 2005. “Do not forget,” Frazier added, “we needed each other to produce some of the greatest fights of all time.”