Faraway Horses (20 page)

Authors: Buck Brannaman,William Reynolds

So there we were: crew, doubles, and equipment all crunched together in the middle of the round corral with a horse running around us. The shot required either Cliff or me to rope Pilgrim’s double, but once we got the job done, we had to get that rope off him before he clotheslined everybody in the middle of the corral, not to mention wiping out all the equipment. The rope had a breakaway honda on it, so all we had to do was pull and it would slip right off.

Still, we had to rope the horse in the right place so the cameras got the shot, plus we had to keep from roping him and the fence at the same time.

Bob and I had been talking about this scene for a few days. Knowing how much he wanted to get things right, I asked if he had ever run up against something like this before.

He told me a story about an incident that occurred while filming his mystical baseball picture

The Natural.

The crew had been working on a shot that had the same linchpin quality as the roping shot we were setting up. That one came during the climactic scene in which Bob’s character, Hobbs, comes to the plate with Wonder Boy, the bat that he’d made as a kid, and gets ready to hit the home run that wins the game.

Bob had hired a professional hitting instructor to work with him on his swing, but he’d gotten so busy with other aspects of making the picture that he hadn’t had time to practice much. The idea was that he’d step up to the plate, swing at a couple of pitches on camera, and then have the professional hit the ball into the seats. The camera’s cutting from the ball as it left the pitcher’s hand to Bob and the bat and back to the ball as it set off the scoreboard fireworks would look like he had hit the home run.

The extras in the grandstands had been kept waiting for hours. They had been given popcorn, candy, and soda pop in an effort to keep them happy. The idea was when the pro stepped in and hit the ball, the crowd would stand up and

cheer as though they were watching a real ballgame. But it had taken so long to get the shot set up, the assistant directors were about half worried that the extras were not going to respond as happy fans were supposed to.

Much to everyone’s surprise, it wasn’t the pro who came out to swing at the pitch. It was Bob. He looked around at the stands filled with people, and, he told me, he got caught up in the moment. He turned to his director of photography and asked, “Why don’t I take a swing or two and see if I can hit the ball.”

Well, who was going to tell him he couldn’t take a pitch in his own movie?

Bob stepped up to the plate and son-of-a-buck if he didn’t drill the ball into the seats. As you can imagine, the crowd of extras went crazy, the camera operator got the shot, and Bob was thrilled. Who wouldn’t have been? Bob is a good athlete, but, as he also told me, that was Redford luck.

The day came when we were finally ready to shoot Pilgrim’s double in the round corral. The plan was now for me to do the roping, since the crew already had film footage of me roping the horse from behind. The shot they now wanted was of Bob swinging a rope as the horse ran past him. He had been swinging pretty well, but nobody wanted him to actually throw a loop because everybody was afraid he’d wipe out all the equipment, not to mention the crew.

Just before the cameras were ready to roll, I leaned over to Bob and said, “Why don’t you try to rope him. You got pretty lucky with that baseball movie. You might just pull this off.”

Needless to say, everybody else was pretty nervous about this swell new idea of mine. They didn’t want to see Bob or anybody else get hurt.

Bob just grinned and said, “Why not?”

As he swung the rope and we drove the horse around the corral, I coached him, “Keep swinging, keep swinging, keep swinging—throw!”

And damned if Bob’s throw didn’t catch the horse around the neck. The crew got the shot. Everybody went crazy, and Bob couldn’t believe it either. He enjoyed the moment so much that he wanted to try it again. I did the best I could to dissuade him. “Why don’t we just be grateful for what we’ve accomplished, and quit while we’re ahead?”

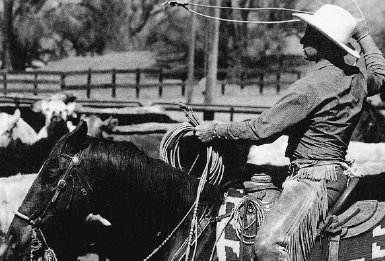

Buck ropes off his big chestnut thoroughbred Pet. Pet has his own claim to stardom as he was one of the horses who played the “lead horse” in the film

The Horse Whisperer.

He thought it over, and knowing that things had worked out as well as they possibly could have, he agreed.

Ironically, one of the most touching scenes we shot wasn’t used in the movie at all.

It featured Grace and Pilgrim at a point in the story where the healing process was beginning. The script called for Grace to enter Pilgrim’s stall. Pilgrim was supposed to still be afraid and worried around humans, so he was to back away from Grace, stop, and then slowly walk up to her. She was then to pet him on the forehead and take his head in her arms.

It was really a moving moment, but the horse that was playing Pilgrim that day was having a little concentration problem and wasn’t performing as we wished.

It had been raining like crazy all day, the way it had all summer, and we’d been working inside for hours because of it. Even though the set was calm, people were frantic at the thousands of dollars a minute they were spending while everybody stood around toeing the dirt.

Three different horses were playing Pilgrim. One, named Pet, was mine. Some of his hair had been clipped and a kind of stain had been applied to his skin to make it look like scabs from his injuries. When I was asked if I had any ideas, I mentioned Pet, who had been standing around all day wearing his Pilgrim makeup.

The first assistant director, Joe Reidy, gulped. “How long’s it going to take you to get him ready?”

I said, “Well, if I don’t have ten or fifteen minutes, I probably can’t get it accomplished.”

He burst out laughing. “I was expecting you to say you needed three or four days or a week.”

The way the scene had been written, Pilgrim didn’t have anything on his head, not even a halter. I had to get the horse to move straight forward and straight back on a line called a mark so that when the cameras were set, his movements were in frame. This was fairly precise work. A few inches either way messed up the shot, and I had to get it done without a halter rope.

I put a rope around one of Pet’s front feet and taught him to move back and forward one step at a time. After a few minutes, I could feed out the end of the rope and he would back straight down the alleyway in the barn. Then, with a little pressure on the rope, he came back to me again.

When I told Reidy I was ready, the crew came back in and we started to shoot the scene. The camera was on a set of narrow tracks so that it could be moved back and forth in the stall to follow Pilgrim’s movements. I sat down between the tracks with the rope laid along the stall floor. Scarlett Johansson, the talented young actress who played Grace, moved into position, with the rope between her feet.

I asked Pet to move back, and he did. Then I jiggled the rope, and he pawed at the dirt as though showing aggression toward her. Finally, I asked him to move slowly toward her. Pet was a horse that truly did love people, and he had a good feel about them. I’d worked with him in a way that he felt a special bond with all humans, so he responded to Scarlett the same as he would have to me.

When I drew the rope in and asked him to lead forward, Pet came up to Scarlett and put his head right in her chest. Scarlett was so moved that she began to cry. So did I, and so did everybody on the crew. To watch that little girl put her arms around that horse’s head and give him a hug and cuddle him was one of the most wonderful things any of us had ever seen. For a brief moment we weren’t filming a movie or doing any other kind of business. We were watching a special moment between a young girl and her horse.

The scene was cut because it detracted from the impact of the end of the movie. Nonetheless, seeing a horse respond to a little girl was a timeless moment, one that happens at barns every day. There’s something magical about a horse and a little girl, and that’s a good story, no matter what.

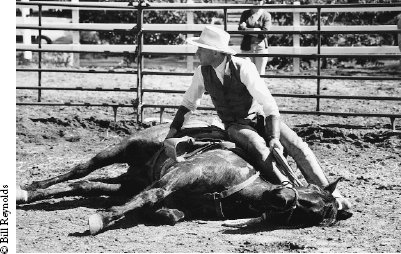

Toward the end of the summer we got ready to shoot the scene in which Bob lays Pilgrim down. As his double, I was the one who was going to do it, and Pet was going to play Pilgrim. In order to make the scene play dramatically, we planned to use a variety of shots and camera angles.

A few days earlier, I’d prepped Pet by laying him down a couple of times, but he’s a relaxed horse and getting him to respond wasn’t a matter of training as much as just asking him to turn loose and give. We wet him down to make him look sweaty, as though he’d been working real hard, and I started laying him down. It was a piece of cake.

Bob was directing the scene from off camera. After a number of takes I went over to him and said, “You know,

this would be a better shot if

you

lay the horse down yourself. You can do it. You don’t need me to double for you.” Bob was a little unsure. He doesn’t make his living working with horses like I do.

I had an idea. I asked the cinematographer, Bob Richardson, who was in between shots, “Do you want to try to lay the horse down?” Richardson said he would. I said, “Step up here and pull on the horn when I tell you.”

Bob was watching, and just as Richardson was about to pull on the saddle horn to lay Pet down, he walked up and said, “Well, if he can do it, I ought to be able to.” Note Bob responding to making the right thing easy!

I said, “Give it a try,” Richardson stepped aside, and Bob gently laid Pet down. There wasn’t anything to it.

Once he was confident that he could do it on camera, Richardson and his crew got the shot set up, and Redford laid the horse down. It was a beautiful shot that worked great because the picture’s star performed the action.

The scene became somewhat controversial because many people thought we were being unkind to the horse. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Laying a horse down is a technique I learned from my teachers, and I’ve used it over the years with horses that are really troubled. Under the right circumstances, it can save a horse’s life by helping him into a frame of mind where he can trust the human. In many cases, this will be the first time in his life that he’s been able to do so.

When I pick up a front leg, the horse is confined and can’t escape. He must begin to trust and not panic so that he

doesn’t flip over backward and hurt himself. First, he must feel confident to move and then stand. I drive him first on three legs to eliminate the danger for him. It usually takes only a few steps for a horse to get comfortable standing on three legs. I start him off on three legs because a horse lies down with his front feet first. By picking up a front leg, I’m putting the horse in a position where he can think that lying down is okay.

The technique has nothing to do with brute force. I don’t throw him down. I work with him by pulling on the saddle horn a little at a time. Every time he gives, I give. Gradually my idea becomes his idea. It occurs to him to relax, give to the rope, and lie down. The closer he gets to the ground, the more relaxed he gets.

A troubled horse may be reluctant at first, but given a little time to search and consider, he will eventually lie down. Usually it doesn’t take more than just a couple of minutes. Quite often, it takes no more than a few seconds.

A really troubled or terrified horse is pretty much convinced that the human is a predator. He’s pretty sure that when he finally does lie down, he’s going to lose the one thing that means everything to him, and that’s his life. This moment is the opportunity to go to your horse. As Tom Booker did with Pilgrim in the movie, you can sit with him, rub him, comfort him, and cuddle him. You can show him that even though you have every opportunity, you won’t take advantage of him. You’re there to be his friend, to be his partner.

Buck “laying down” a horse.

When the horse lies down and finds that your response is different from what he expected, you have an opportunity to bond that you never could have gotten any other way. Then, after the horse gets up, you have the further opportunity to accomplish things with him without much of the defensive behavior that has inhibited his ability to change.