Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (44 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

Looking Back

Warning Signs: Showcasing Misleading Metrics That Overstate Performance

• Changing the definition of a key metric

• Highlighting a misleading metric as a surrogate for revenue

• Unusual definition of organic growth

• Divergence in trend between same-store sales and revenue per store

• Inconsistencies between the earnings release and the 10-Q

• Highlighting a misleading metric as a surrogate for earnings

• Pretending that recurring charges are nonrecurring in nature

• Pretending that one-time gains are recurring in nature

• Highlighting a misleading metric as a surrogate for cash flow

• Headlining a misleading metric on the earnings release

Looking Ahead

In Chapter 15, we shift from key metrics that present an overly optimistic view of a company’s performance to those metrics that mislead investors about a potentially imminent deterioration in the Balance Sheet and the company’s economic health.

15 – Key Metrics Shenanigan No. 2: Distorting Balance Sheet Metrics to Avoid Showing Deterioration

As well as writing books, we also love reading them. We always make it a point to stop into bookstores as often as possible, whether it’s mega-chains like Barnes & Noble or the literary jewel of Portland, Powell’s Books. Once we’re inside one of these places, it’s hard not to notice the scores of self-help and diet books. They are everywhere. No doubt, we all yearn to look, feel, and be better at work, play, and all the other stuff. It’s certainly a big business teaching people to feel better about their lives and to look fabulous.

A lot of diet books still advocate the perennially popular granddaddy of slimming solutions, Weight Watchers. This classic diet allows you to eat whatever you want, but restricts total calories and fat. The Atkins program, in contrast, trumpets the virtues of loading up your body with foods that are high in fat, but severely restricting the intake of carbohydrates. The popular South Beach diet offers a variation on Atkins by limiting the consumption of “bad” carbs and increasing the consumption of “good” fat. And finally, the plan endorsed by the medical establishment today limits consumption of both fats and carbs and instead loads you up on veggies and basically expects you to graze like a cow.

Who knows if any of these plans can really make us healthier or make us look any better? We do know, however, that upper management spends a great deal of time trying to make its Balance Sheets look great, even if they are loaded up with junk. This chapter highlights four techniques that struggling companies might use to convince investors that the company not only looks great, but is in excellent health. Hopefully these folks won’t be as effective in fooling investors as the diet book authors are in persuading readers to trust their advice.

Techniques to Distort Balance Sheet Metrics to Avoid Showing Deterioration

1. Distorting Accounts Receivable Metrics to Hide Revenue Problems

2. Distorting Inventory Metrics to Hide Profitability Problems

3. Distorting Financial Asset Metrics to Hide Impairment Problems

4. Distorting Debt Metrics to Hide Liquidity Problems

1. Distorting Accounts Receivable Metrics to Hide Revenue Problems

Company managements are well aware that investors review working capital trends carefully to spot signs of poor earnings quality or operational deterioration. They realize that a surge in receivables that is out of line with sales will lead investors to question the sustainability of recent revenue growth. What easier way could there be to keep these questions at bay and give investors what they cherish (stable receivable growth) than by distorting the numbers? This first section deals with games to keep the reported accounts receivable lower by (1) selling them, (2) converting them into notes receivable, or (3) moving them somewhere else on the Balance Sheet.

Selling Accounts Receivable.

In Chapter 10, “CF Shenanigan No. 1: Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section,” we discussed how selling accounts receivable may be considered a useful cash-management strategy, but an unsustainable longer-term driver of cash flow growth. Selling accounts receivable also serves another useful purpose: it lowers the days’ sales outstanding (DSO) reported to investors (meaning that it makes it appear that customers have been paying more quickly). Dishonest management can easily conceal a jump in DSO simply by selling more accounts receivable.

Let’s refer back to our discussion in Chapter 10 of Sanmina-SCI’s stealth sales of receivables. After selling these receivables, the company highlighted a decline in DSO and an increase in cash flow from operations (CFFO) in its September 2005 quarterly results. Astute investors clearly understood that it was the sale of receivables, not operational efficiencies, that drove DSO lower and CFFO higher. Such investors understand that the sale of receivables, in substance, represents a financing decision (that is, collecting cash due on customer accounts earlier). Therefore, the now lower accounts receivable balance naturally also results in a smaller DSO figure.

Tip:

Whenever you spot a CFFO boost from the sale of receivables, also realize that by definition, the company’s DSO will have been lowered as well.

Also recall how Peregrine recorded bogus revenue and then shamelessly faked the sale of the related bogus accounts receivable in order not to raise any alarms. Those receivables, obviously, went uncollected, and management became concerned that the bulging account balance would drive up DSO indefinitely—a clear warning for investors. By faking the sale of these receivables, Peregrine inflated its CFFO and removed the DSO red flag from investors’ sights in one fell swoop.

Tip:

To calculate DSO on an apples-to-apples basis, simply add back sold receivables that remain outstanding at quarter-end for all periods.

The first examples of lowering receivables to improve DSO involved either selling them outright or faking the sale. Another popular way to hide accounts receivables is simply to reclassify them elsewhere on the Balance Sheet, like notes receivable.

Turning Accounts Receivable into Notes Receivable

. When we introduced Symbol Technologies in Chapter 1, we discussed management’s easy, yet dishonest, solution to its mid-2001 “receivables problem.” Symbol’s receivables had been growing rapidly as a result of aggressive revenue recognition and channel stuffing, surging to 119 days in June 2001 (up from 94 in March 2001 and 80 in June 2000). To allay investor concerns, management engineered a cosmetic reduction in accounts receivable.

It was a pretty dirty trick, in our view. Symbol simply asked some of its closest customers to sign paperwork that would convert these trade accounts receivable into promissory notes or loans. Apparently they acquiesced, since it made little difference to them; they owed the money either way. However, the new paperwork gave Symbol a convenient cover to move these accounts receivable to the notes receivable section of the Balance Sheet. In effect, Symbol waved a magic wand and, with the help of some compliant customers, “reclassified” these trade receivables to an account that is not closely monitored by many investors. It seems that Symbol’s primary purpose for this reclassification was to lower its DSO in order to fool investors into assuming that sales had been kosher and customers had paid on time. And, according to plan, DSO fell from the 119 days in June 2001 to 90 days the following period, and unquestioning investors mistakenly proclaimed that the “receivables problem” had been solved.

Tip:

Investors should be as concerned when they see a

large decrease in DSO

(particularly following a period of rapidly rising DSO) as they are when they see a large increase in DSO.

Watch for Increases in Receivables Other Than Accounts Receivable

. UTStarcom pulled a similar switcheroo in 2004 by taking more payment in the form of “bank notes” and “commercial notes.” Since these notes receivable were not categorized as accounts receivable on the Balance Sheet (in fact, the bank notes were considered cash), UTStarcom was able to present a more palatable DSO to investors, despite a severe deterioration in its business. Diligent investors could easily have spotted this improper account classification by reading UTStarcom’s footnotes. As shown in the accompanying box, the company disclosed clearly that it had accepted a substantial amount of bank and commercial notes in place of accounts receivable.

UTSTARCOM’S JUNE 2004 FORM 10-Q

From Footnote 6 (cash, cash equivalents and Short-Term Investments

)

The Company

accepts bank notes receivable

with maturity dates between three and six months

from its customers

in China in the normal course of business.

Bank notes receivable were $100.0 million and $11.5 million at June 30, 2004 and December 31, 2003

, respectively, and have been included in cash and cash equivalents and short-term investments. [Italics added for emphasis.]

From Footnote 8 (accounts and notes receivable)

The Company

accepts commercial notes receivable

with maturity dates between three and six months

from its customers in China

in the normal course of business. Notes receivable available for sale were

$42.9 million and $11.4 million at June 30, 2004 and December 31, 2003

, respectively. [Italics added for emphasis.]

Investors received another warning on UTStarcom’s Balance Sheet: notes receivable surged, from $11 million in December 2003 to $43 million the following quarter. By now, it should be abundantly clear that identifying the reason for such a change is extremely important. If management cannot provide you with a plausible reason, assume that it is playing a game with accounts receivable and trying to hide a bulging DSO. In the case of UTStarcom, you would have solved the mystery by simply reading the footnotes that disclosed that these notes receivable, effectively, had been transformed from accounts receivable.

Watch Out for Varying Company DSO Calculations.

For the purposes of identifying aggressive revenue recognition practices, we suggest that investors use the ending (not the average) receivables balance. Using average receivables works fine when investors are trying to assess cash-management trends, but it works less well when they are trying to detect financial shenanigans. Investors who are searching for shenanigans should use the DSO calculation with ending receivables and ignore companies if they tell you that your DSO calculation is incorrect or is not in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). (Of course, DSO, like all other non-GAAP metrics, is outside of the rule makers’ purview.)

Accounting Capsule: Days’ Sales Outstanding (DSO)

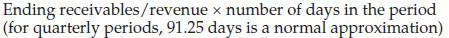

Days’ sales outstanding (DSO) is generally calculated as follows:

While we recommend using this calculation for DSO, you may encounter different calculations suggested by companies or texts. For example, some people believe that DSO should be calculated using average receivables over the period, as opposed to the ending balance of receivables that we suggest.

Since DSO is not a GAAP metric, there is no absolute definition for it. It is important, however, that the calculation reflects the analysis that you are trying to perform. For example, if you are assessing the likelihood that a company has accelerated revenue by booking a significant amount of revenue on the last day of the quarter, (i.e., stuffing the channel), it makes sense to calculate DSO using the ending balance of receivables rather than the average one. Similarly, if you are worried about the collectibility of receivables and you are evaluating a company’s exposure, it is best to use the ending balance. However, if you wish to calculate the average time over which a company collects its receivables, you may want to use the average balance of receivables.