Gallipoli (50 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

Of course, upon hearing the stories, the men of the Light Horse have one principal reaction. They want to go â are

desperate

to go â and support the âbeetle-crushers'. Yes, the Light Horse would love to take their Walers, but as soldiers of the King they are prepared to leave the horses behind and serve as required.

âCan you wonder,' Trooper Bluegum would recount, âthat the Light Horse wanted to get a move on and make a start for the front? Can you wonder that when we heard of the terrible list of casualties which were the price of victory, and when we saw our men coming back â many of them old friends, with their battle-scars upon them, we fretted and fumed impatiently? ⦠We could stand it no longer. Our boys needed reinforcements, and that was all we cared about. They must have reinforcements.'

57

Colonel Granville de Laune Ryrie, Commander of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, gets word to General Birdwood: âMy brigade are mostly bushmen, and they never expected to go gravel-crushing, but if necessary the whole brigade will start to-morrow on foot, even if we have to tramp the whole way from Constantinople to Berlin.'

58

Colonel Sir Henry George Chauvel of the 1st Light Horse Brigade and Brigadier-General Andrew Hamilton Russell of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles make similar offers. They

insist

on going.

2â3 MAY 1915, TIME FOR THE ANZACS TO BREAK OUT

While it is oft said of newborn babies that they only really âstart to look like themselves' a week or so after the trauma of birth, the same is true, oddly enough, of battlefields in trench warfare. For while the perimeters of the Anzac battlefield had been as fluid as they were primitive on the first day, changing with the ebb and flow of the cataclysmic clashes, now they are broadly static, battle-worn ⦠and getting deeper all the time. Both sides keep digging furiously their roughly parallel trenches around the approximately 1000-acre footprint of the Anzac occupation.

All the dirt so furiously flung onto mounds in front of the trenches is moulded into solid parapets that face the enemy. The soldiers create âloopholes' in the parapets â narrow vertical openings through which they can fire their rifles. On both sides, the frontline firing trenches are often dug in zigzags or with boxed recesses, so that if an enemy captures one end, they can't simply fire a machine-gun down a straight corridor to capture the lot. The more sophisticated trenches have âfiring steps', large ledges cut into the side of the trench that the soldiers can stand upon as they are firing and use to propel themselves up and over when the time comes. Branching off from those main trenches in all directions are âsaps', trenches initially built forward into no-man's-land to allow the soldiers to better observe (or even hear) the enemy. These may be developed to use in an attack. Then there are the communication trenches, used for everything from supplying the for'ard ones and connecting tiers of trenches to allowing platoons to get into and out of the frontlines safely.

Back from those trenches are the âdugouts', effectively small caves and hollows that the men have fashioned, allowing them shelter from the weather and, more importantly, the shrapnel. From some of these dugouts, the men can look out on the Aegean Sea â when the mists lift it presents a sparkling blue vista â and there, just a few horizons over, is the island of Imbros. Close to the shore, there is always a flurry of vessels going to and fro, keeping the men ashore supplied, the whole thing a vision splendid.

But near to them, on land? Not so calm â¦

Terrain that used to be low shrub on solid ground is now more often âa ploughed and shrivelled waste of broken water-bottles, bayonets, fragments of bombs, barbed wire entanglements shattered and shattered again ⦠battered rifle butts and the shreds that were once human clothes'.

59

Ever and always, there is a constant traffic of men in the hills, mostly bringing supplies up and too often taking wounded and dead bodies down. (Of the latter, most have been shot through the head, as that is the most frequently available target for the Turks, poking up above the trenches â and most of the bodies are missing brains, as at such short range the bullets usually scoop out the lot.)

Thus, a week in, Gallipoli really is starting to look like itself.

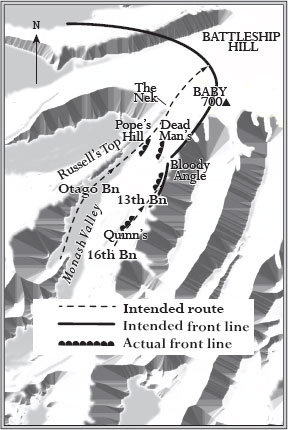

All of the main positions now have â or soon will have â names that indicate at least something of the horror of what goes on there: the Bloody Angle, Dead Man's Hill, Sniper's Nest, Hell Spit, Casualty Corner, Valley of Despair and Shell Green â a rare fleck of green field now holed all over by the Turkish shells.

Shrapnel Gully leads into Monash Valley, and it is at the end of this valley that the most dangerous Anzac posts are found, most of them with curiously benign names, despite the fact that they have seen the most bloodshed: Quinn's Post, Pope's Hill, Courtney's Post, Steele's Post, the Nek.

Their distinguishing feature is that they are all so close to the enemy trenches that the combatants can usually hear each other

talk

, and often throw bombs at one another.

There is no more dangerous spot in Anzac than the one named after Major Hugh Quinn of 15th Battalion, the unit that first held it. Quinn's Post lies at the northern end of the Second Ridge, 800 yards below Baby 700, the hill that gazes out upon Monash Valley and sits âover Anzac like a tyrannical parent'.

60

It is the most advanced easterly position in the entire Anzac line and the spot where the Australian and Turkish trench systems come closest to touching. It is just ten yards away from the Turks in some parts. To make things even worse, the post is situated in a 40-foot dip, and Turkish snipers gaze down upon it from three sides â¦

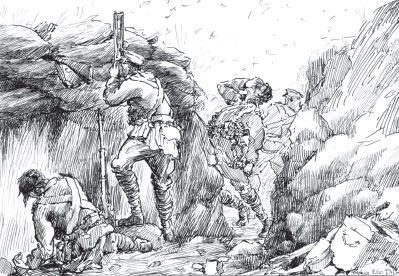

âIn the Trenches, Quinn's Post', by Ellis Silas (AWM ART90798)

Just five yards directly behind the Anzacs is the precipice of Monash Valley. Quinn's is therefore the key to the defence of Shrapnel Gully and Monash Valley, and if it is lost, the Turks would likely break through to the heart of the Anzacs and the entire front would then be lost.

Baby 700 is bedecked with three tiers of Turkish trenches, giving their elevated artillery and snipers the capacity to fire on most of the aforementioned posts, together with the precarious supply line that wends its way through Shrapnel Gully and Monash Valley.

The entire left flank of the Anzac perimeter is overlooked and threatened by Baby 700.

Failed Attack on Baby 700, by Jane Macaulay

Now, a week in from the landing, Generals Birdwood and Godley decide that the New Zealand Brigade, commanded by Colonel Francis Johnston, and the Australian 4th Brigade under Colonel John Monash must, at all costs, capture Baby 700.

At 2.15 pm on the afternoon of 2 May, Godley tells Monash of the plan and the 4th Brigade's place in the scheme of things.

In a few hours' time, at 7 pm, the land-based artillery and naval guns would start a bombardment on the Turkish trenches on Baby 700.

That barrage would lift at 7.15 pm, moving to the hills farther up the Sari Bair Range, and at that instant the attack would start.

Baby 700 will soon be theirs.

Now, no matter that Colonel Monash is a man who was not only born confident but has also always managed to project that confidence onto others â he does not like this particular situation at all.

Not at all.

A careful, logical engineer of some brilliance in civilian life, he likes considered, ordered approaches to problems, and this is quite the opposite. He is receiving his orders just five hours before the attack is meant to start, with entirely insufficient numbers of men for the task, against a heavily entrenched, armed and supplied enemy who would be expecting their attack. This is what he later calls the âChurchill way of rushing in before we are ready, and hardly knowing what we are going to do next â¦'

61

Still, he must follow orders just as his men must, including Ellis Silas, who, once he hears that they are to charge from a trench straight at the enemy, immediately worries:

I wonder how I shall get on in a charge, for I have not the least idea how to use a bayonet; even if I had, I should not be able to do so, the thing is too revolting â I can only hope that I get shot â why did they not let me do the [stretcher] work? I have told the authorities often enough that I cannot kill

.

62

And now Ellis has to run a message and very nearly gets killed by snipers, in part because he is not moving fast enough.

âRun for it, you damned fool!' Captain Eliezer Margolin shouts. And now all the men join in: âRun, Silas,

run for it!

The snipers will get you!'

63

Strangely, Ellis â whose mouth now seems almost permanently set in an expression of tight horror, as if always trying not to scream, just as his once soft hands are now nearly always clenched fists â doesn't particularly care to run, finally reasoning that if he is destined to die on this day then there is likely little he can do about it. Besides which, he is simply tired of never being able to move about with freedom.

At 6.30 pm, just as the setting sun lights the top of the hill that is their goal with a curious hue of rose and gold, it is time for the 4th Brigade to get into position.

The plan is for them to climb the steep side of Bloody Angle and start their rush on the crest at 7.15 pm, once the bombardment on the Turkish positions stops. For now, things are remarkably quiet.

Ellis Silas's 16th Battalion is in the middle, flanked on the left by the 13th Battalion and on the right by the 15th Battalion. Ellis himself has a stricken, uneasy look on his face as he awkwardly cradles his weapon in his soft hands that are far more suited to wielding a paintbrush.

And now the naval barrage starts, the loudest and most intense they have ever heard, hopefully raining down hell on the Turks. The Australian soldiers stand on the firing step and wait, straining, âtense, expectant, like dogs in the leash, every muscle strained for the moment of attack â a few whispered orders, the tightening of buckle and strap â the stealthy loosing of the bayonet from its scabbard'.

64

Just before 7 pm, the barrage stops, and Lieutenant Cyril Geddes of the 16th Battalion looks at his watch. All around him, the Australian soldiers wait, hanging on his words. âIt is 7 o'clock, lads,' he calls. âCome on, lads, at 'em!'

65

And with a cry they go, scrabbling out of the trenches, trying to scramble upwards, gripping soil that comes away at their touch.

Instantly, and exactly as Monash has feared, his men come under withering fire as tier after tier of well-protected Turks in their trenches on Baby 700 pour heavy rifle and machine-gun fire onto his men, joined by the Turkish soldiers at Bloody Angle, who together with their furious fusillade of bullets also roll bombs down upon the Australians.

The carnage is fearful. Ellis Silas survives, despite having to go back and forth as a messenger, seeking more ammunition to be sent up to those on the frontline:

In a very few minutes the gully at the foot of the hill was filled with dead and wounded â these poor lumps of clay had once been my comrades, men I had worked and smoked and laughed and joked with â oh God, the pity of it. It rained men in this gully; all round could be seen the sparks where the bullets were striking

.

66

And who should be strutting around in the middle of this hell on earth? It is none other than General Godley, and he wishes to speak to Ellis. âYour puttee's undone, young man â¦'

âYes, sir, that's all right,' Silas replies. âI'll soon fix that up, but for God's sake, take cover. You'll be killed.'

67

General Godley does not. Like many of the Generals, it is a point of honour not to show fear; he thinks it bad for the men's morale. Someone must show themselves to be fearless on the day, and it is just as well that it is the senior officers.