Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill (64 page)

Read Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill Online

Authors: Candice Millard

Tags: #Military, #History, #Political, #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Europe, #Great Britain

BOOK: Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill

7.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

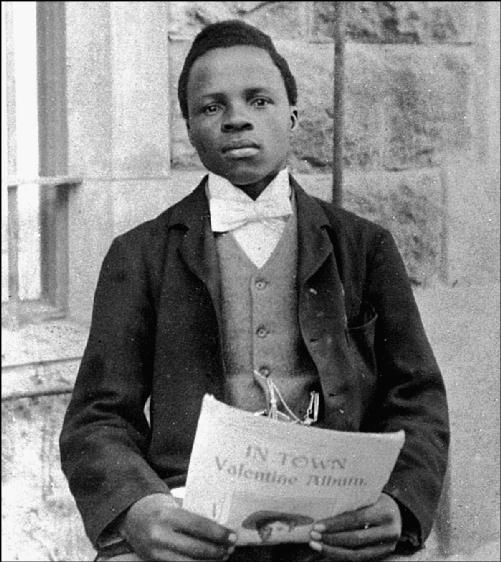

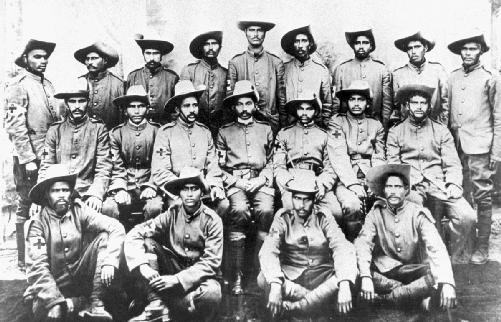

The Boers were well known not only for their fierce independence but for their harsh treatment of native Africans and Indians. Among the most effective advocates for these groups in southern Africa were Solomon Plaatje (

above

) a brilliant young journalist and linguist who would become the first secretary of the African National Congress (ANC), and Mohandas Gandhi (

following

), seated exact center, who led a team of stretcher-bearers on some of the most blood-soaked battlefields of the war.

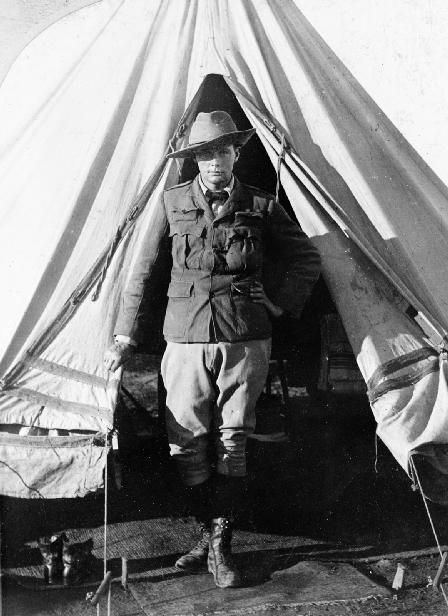

Churchill set sail for South Africa just two days after war was declared. Hired as a correspondent by the

Morning Post

, he quickly made his way to the heart of the war, settling into a bell tent with two other journalists. “I had not before encountered this sort of ambition,” one of his tent mates would later write of Churchill, “unabashed, frankly egotistical, communicating its excitement, and extorting sympathy.”

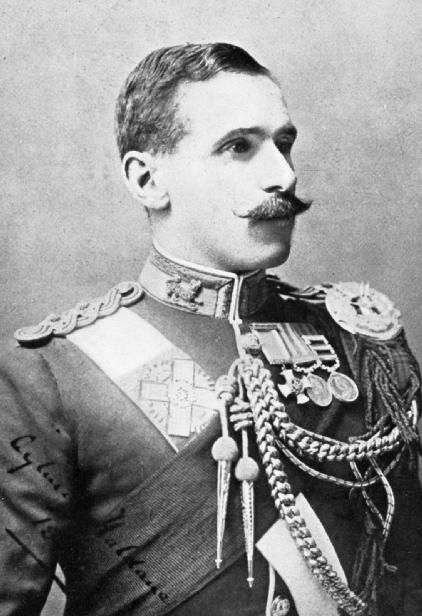

Soon after arriving in South Africa, Churchill was reunited with an old friend, Aylmer Haldane, who had already been injured in one of the first battles of the war. Assigned to take command of an armored train on a reconnaissance mission, Haldane invited Churchill to come along. Churchill immediately agreed, notwithstanding the grave danger involved.

“Nothing looks more formidable and impressive than an armoured train,” Churchill wrote, “but nothing is in fact more vulnerable and helpless.” Crowded into open cars with little more than their peaked helmets to protect them, the men were sitting targets for the Boers, who needed only wait for them to come rattling along the tracks into their sights.

On November 15, 1899, just a month after Churchill arrived in South Africa, Louis Botha led a devastating attack on the armored train that carried Churchill, Haldane and his men. In the midst of a hailstorm of bullets and shells, the train was thrown from the tracks, leaving several men dead and dozens more seriously wounded. Rushing down from the surrounding hills, the Boers captured some sixty men, among them Winston Churchill.

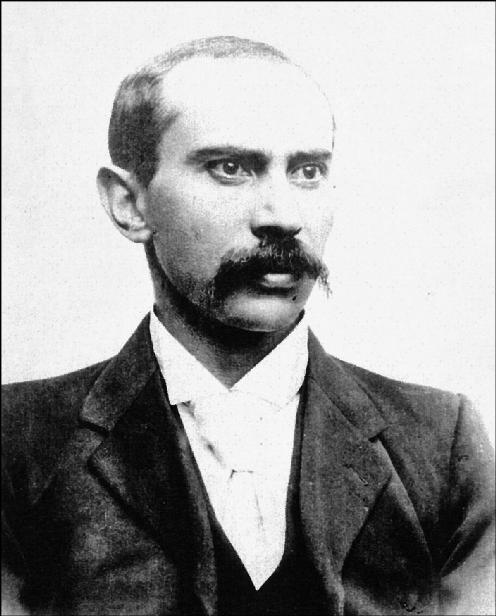

Three days after the attack on the armored train, Churchill arrived in Pretoria, the Boer capital, with the other British prisoners of war. Surrounded by curious Boers eager to see the new prisoners, he glared back at them with unconcealed hatred and resentment. Although he respected the enemy on the battlefield, the idea that average Boers would have any control over his fate enraged him.

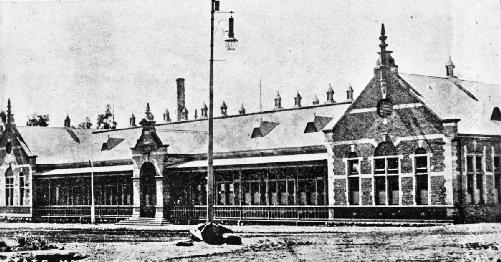

Churchill was imprisoned with about a hundred British officers in the Staats Model School. Used as a teachers college before the war, the building was now surrounded by a corrugated-iron paling and heavily armed Boers. Churchill hated his imprisonment, he later wrote, “more than I have ever hated any other period in my whole life.”

Furious and frustrated at finding himself captive while the war raged on without him, Churchill turned for help to Louis de Souza, the Transvaal secretary of state for war. Although he befriended Churchill, even bringing him a bottle of whiskey hidden in a basket of fruit, de Souza could not give the young reporter the only thing he wanted—his freedom.

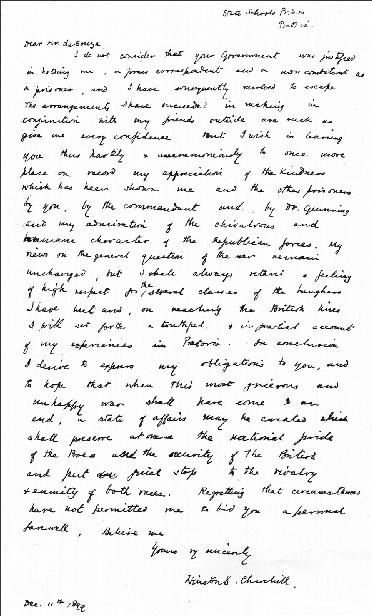

Finally realizing that the Boers would never let him go as long as they were at war, Churchill decided to escape. To the Boers’ fury, he not only slipped through their fingers but left behind a maddeningly arrogant note, addressed directly to de Souza. “Regretting that circumstances have not permitted me to bid you a personal farewell,” he wrote before scaling the prison fence, “Believe me Yours vy sincerely, Winston Churchill.”

Other books

Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis

Hyacinth by Abigail Owen

The Gamma Option by Jon Land

The First Night by Sidda Lee Tate

Wolf Tales VI by Kate Douglas

Hammer & Air by Amy Lane

Alone by Erin R Flynn

Agents of Artifice: A Planeswalker Novel by Ari Marmell

The Atomic Weight of Secrets or The Arrival of the Mysterious Men in Black by Eden Unger Bowditch

curse of the alpha - episode 03 & 04 by tasha black