Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill (65 page)

Read Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape, and the Making of Winston Churchill Online

Authors: Candice Millard

Tags: #Military, #History, #Political, #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Europe, #Great Britain

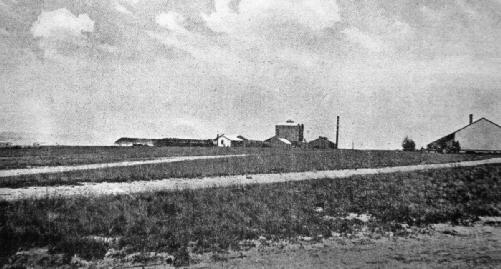

After striking out on his own, attempting to cross hundreds of miles of enemy territory without a map, compass, weapon or food, Churchill stumbled upon the Transvaal and Delagoa Bay Colliery. Taking a wild chance that he might find help there, he forced himself to come out of hiding, stepping out of “the shimmering gloom of the veldt into the light of the furnace fires.”

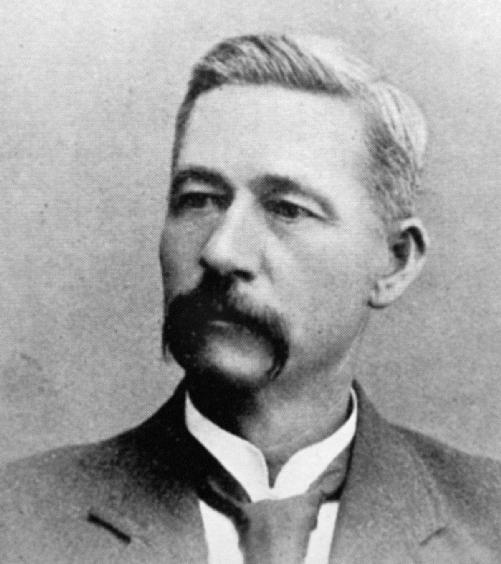

By an incredible stroke of luck, Churchill knocked on the door of John Howard, the mine’s manager and one of the few Englishmen who had been allowed to remain in the Transvaal during the war. When Howard agreed to help him, Churchill would later write, “I felt like a drowning man pulled out of the water.”

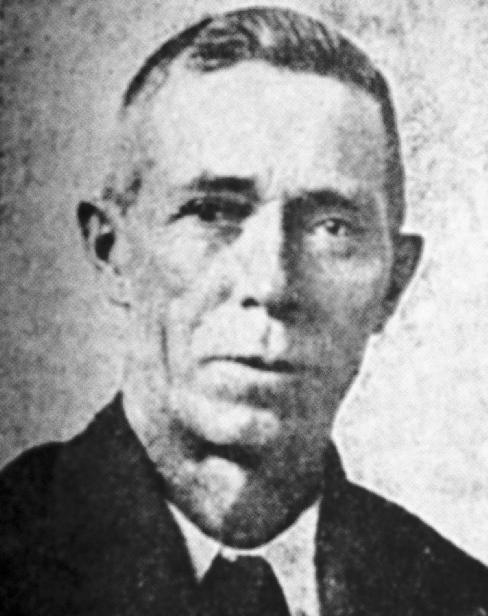

After hiding Churchill in a rat-infested coal mine shaft, Howard finally found a way to secret him out of the country—burrowed deep inside the wool trucks of the mine’s storekeeper, Charles Burnham. Burnham not only agreed to let Churchill hide in his trucks, he rode with him all the way to Portuguese East Africa, bribing guards and inspectors at every stop.

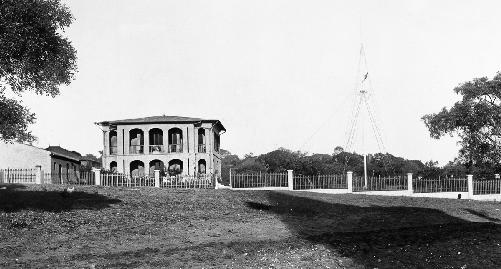

When Churchill finally arrived in Lorenço Marques, the capital of Portuguese East Africa, he quickly made his way to the British consulate. Although Britons and Boers alike were desperately trying to find him, when Churchill arrived at the consulate, covered in coal dust, the secretary did not recognize the filthy young man standing before him. “Be off,” he sneered. “The Consul cannot see you to-day.”

As soon as the success of his escape was known, Churchill became a national hero, greeted in Durban, the largest city in British-held Natal, by cheering throngs. “I was nearly torn to pieces by enthusiastic kindness,” he later recalled. “Whirled along on the shoulders of the crowd, I was carried to the steps of the town hall, where nothing would content them but a speech.”

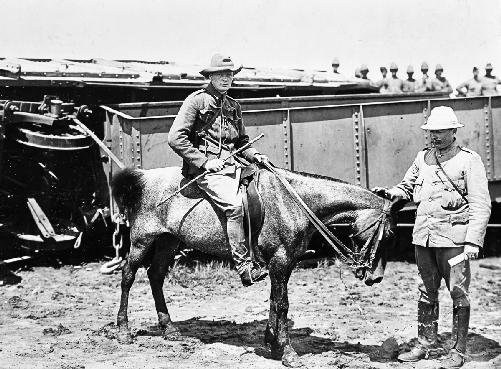

After delivering his speech in Durban, Churchill returned to the scene of his capture, inspecting the wreckage of the armored train he had fought to save and spending Christmas Eve in a tent that had been erected on the same railway cutting where he had been forced to surrender.

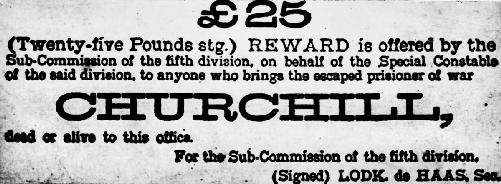

This wanted poster, distributed in the wake of Churchill’s escape, offered a reward for his capture, “dead or alive.” When he saw the poster, Churchill’s only complaint was that the reward was so small. “I think you might have gone as high as £50,” he wrote to the poster’s author, “without an overestimate of the prize.”

As soon as he was free, Churchill wanted to fight. After convincing Buller to give him a commission in the South African Light Horse, he took part in several pivotal battles before returning to Pretoria, where he and his cousin, the 9th Duke of Marlborough, freed the jubilant men who had so recently been Churchill’s fellow prisoners.

Just six months after his escape, Churchill ran for Parliament for the second time. This time, to no one’s surprise, least of all his own, he won. “It is clear to me from the figures,” he wrote to the prime minister, “that nothing but personal popularity arising out of the late South African War, carried me in.”

Cover, foreground photograph:

Winston Churchill at the time of the Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan, one year before he set sail for South Africa. As a young British officer in fierce colonial battles on three continents, Churchill resolved to become noticed at all cost, setting the stage for his capture and daring escape during the Boer War.

Background photograph:

British soldiers and officers watching the disastrous Battle of Colenso, which played out during Churchill’s escape from the Boers and left England desperate for a hero.