How We Learn (19 page)

Authors: Benedict Carey

It’s unlikely that scientists will ever give us specific incubation times for specific kinds of problems. That’s going to vary depending on who we are and the way we work, individually. No matter. We can figure out how incubation works for ourselves by trying out different lengths of time and activities. We already take breaks from problem solving anyway, most of us, flopping down in front of the TV for a while or jumping on Facebook or calling a friend—we take breaks and feel guilty about it. The science of insight says not only that our guilt is misplaced. It says that many of those breaks

help

when we’re stuck.

When I’m stuck, I sometimes walk around the block, or blast some music through the headphones, or wander the halls looking for someone to complain to. It depends on how much time I have. As a rule, though, I find the third option works best. I lose myself in the kvetching, I get a dose of energy, I return twenty minutes or

so later, and I find that the intellectual knot, whatever it was, is a little looser.

The weight of this research turns the creeping hysteria over the dangers of social media and distracting electronic gadgets on its head. The fear that digital products are undermining our ability to think is misplaced. To the extent that such diversions steal our attention from learning that requires continuous focus—like a lecture, for instance, or a music lesson—of course they get in our way. The same is true if we spend half our study time on Facebook, or watching TV. The exact opposite is true, however, when we (or our kids) are stuck on a problem requiring insight and are motivated to solve it. In this case, distraction is not a hindrance: It’s a valuable weapon.

As for the kid in the auditorium on the morning of my presentation, I can’t know for sure what it was that helped him solve the Pencil Problem. He clearly studied the thing when I drew those six pencils side by side on the chalkboard—they all did. He didn’t get it right away; he was stuck. And he had several types of incubation opportunities. He was in the back with his friends, the most restless part of the auditorium, where kids were constantly distracting one another. He got the imposed break created by the SEQUENC_ puzzle, which held the audience’s attention for a few minutes. He also had the twenty minutes or so that passed after several students had drawn their first (and fixed) ideas, attempting to put all the triangles onto a flat plane. That is, he had all three types of the breaks that Sio and Ormerod described: relaxation, mild activity, and highly engaging activity. This was a spatial puzzle; any one of those could have thrown the switch, and having three is better than having just one, or two.

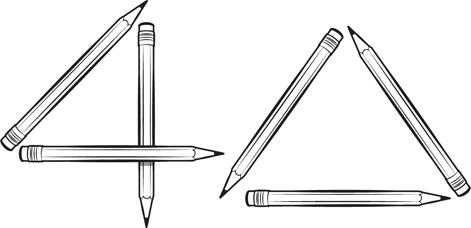

Let’s reset the problem, then: Given six identical pencils, create four equilateral triangles, with one pencil forming the side of each triangle. If you haven’t solved it already, try again now that you’ve been at least somewhat occupied by reading this chapter.

Got the answer yet? I’m not going to give it away, I’ve provided too many hints already. But I will show you what the eleven-year-old scratched on the board:

Take that, Archimedes! That’s a stroke of mad kid-genius you won’t see in any study or textbook, nor in early discussions of the puzzle, going back more than a hundred years. He incubated that one all on his own.

*1

Here’s a famous one that used to crease the eyebrows of my grandparents’ generation: A doctor in Boston has a brother who is a doctor in Chicago, but the doctor in Chicago doesn’t have a brother at all. How is that possible? Most people back then just assumed that any doctor must be a man, and thus came up with tangled family relations based on that mental representation. The answer, of course, is that the doctor in Boston is a woman.

*2

You find yourself in a stadium, in front of a crowd, a pawn in a cruel life-or-death game. The stadium has two closed doors, a guard standing in front of each one. All you know is that behind one door is a hungry lion, and behind the other is a path out of the stadium—escape. One guard always tells the truth, and the other always lies, but you don’t know which is which. You have one question you can ask of either guard to save your life. What’s the question?

Chapter Seven

Quitting Before You’re Ahead

The Accumulating Gifts of Percolation

I think of incubation, at least as scientists have described it, as a drug. Not just any drug, either, but one that’s fast-acting, like nicotine, and remains in the system for a short period of time. Studies of incubation, remember, have thus far looked almost exclusively at short breaks, of five to twenty minutes. Those quick hits are of primary interest when investigating how people solve problems that, at their core, have a single solution that is not readily apparent. Geometric proofs, for example. Philosophical logic. Chemical structures. The Pencil Problem. Taking an “incubation pill” here and there, when stuck, is powerful learning medicine, at least when dealing with problems that have right and wrong answers.

It is hardly a cure-all, though. Learning is not reducible to a series of discrete puzzles or riddles, after all; it’s not a track meet where we only have to run sprints. We have to complete decathlons, too—all those assignments that require not just one solution or skill but many, strung together over time. Term papers. Business plans. Construction blueprints. Software platforms. Musical compositions, short stories,

poems. Working through such projects is not like puzzle solving, where

the

solution suddenly strikes. No, completing these is more like navigating a labyrinth, with only occasional glimpses of which way to turn. And doing it well means stretching incubation out—sometimes way, way out.

To solve messier, protracted problems, we need more than a fast-acting dose, a short break here and there. We need an

extended-release

pill. Many of us already take longer breaks, after all—an hour, a day, a week, more—when working through some tangled project or other. We step away repeatedly, not only when we’re tired but often because we’re stuck. Part of this is likely instinctive. We’re hoping that the break helps clear away the mental fog so that we can see a path out of the thicket.

The largest trove of observations on longer-term incubation comes not from scientists but artists, particularly writers. Not surprisingly, their observations on the “creative process” can be a little precious, even discouraging. “My subject enlarges itself, becomes methodized and defined, and the whole, though it be very long, stands almost complete and finished in my mind, so that I can survey it, like a fine picture or a beautiful statue, at a glance,”

reads a letter attributed to Mozart. That’s a nice trick if you can pull it off. Most creative artists cannot, and they don’t hesitate to say so. Here’s the novelist Joseph Heller, for example, describing the circumstances in which valuable ideas are most likely to strike. “I have to be alone. A bus is good. Or walking the dog. Brushing my teeth was marvelous—it was especially so for

Catch-22

. Often when I am very tired, just before going to bed, while washing my face and brushing my teeth, my mind gets very clear … and produces a line for the next day’s work, or some idea way ahead. I don’t get my best ideas

while actually writing.”

Here’s another, from the poet A. E. Housman, who would typically take a break from his work in the trough of his day to relax. “Having drunk a pint of beer at luncheon—beer is a sedative to the

brain and my afternoons are the least intellectual portion of my life—I would go out for a walk of two or three hours. As I went along, thinking of nothing in particular, only looking at things around me following the progress of the seasons, there would flow into my mind, with sudden unaccountable emotion, a line or two of verse, sometimes a whole stanza at once, accompanied, not preceded, by a vague notion of the poem which they were destined to form part of.” Housman was careful to add that it was

not

as if the entire poem wrote itself. There were gaps to be filled, he said, gaps “that had to be taken in hand and completed by the mind, which was apt to be a matter of trouble and anxiety, involving trial and disappointment,

and sometimes ending in failure.”

Okay, so I cherry-picked these quotes. But I cherry-picked them for a reason: because they articulate so clearly an experience that thousands of creative types have described less precisely since the dawn of introspection. Heller and Housman deliver a clear blueprint. Creative leaps often come during downtime that follows a period of immersion in a story or topic, and they often come piecemeal, not in any particular order, and in varying size and importance. The creative leap can be a large, organizing idea, or a small, incremental step, like finding a verse, recasting a line, perhaps changing a single word. This is true not just for writers but for designers, architects, composers, mechanics—anyone trying to find a workaround, or to turn a flaw into a flourish. For me, new thoughts seem to float to the surface only when fully cooked, one or two at a time, like dumplings in a simmering pot.

Am I putting myself in the same category as Housman and Heller? I am. I’m putting you there, too, whether you’re trying to break the chokehold of a 2.5 GPA or you’re sitting on a full-ride offer from Oxford. Mentally, our creative experiences are more similar than they are different.

*

This longer-term, cumulative process is distinct enough from the short-term incubation we described in the last chapter that it warrants another name. Let’s call it

percolation

. Let’s take it as given that it exists, and that it’s a highly individual experience. We can’t study percolation in any rigorous way, and even if we could—(“Group A, put down your pen and go take a walk in park; Group B, go have a pint of ale”)—there’s no telling whether what works for Heller or Housman is right for anyone else. What we can do is mine psychological science for an explanation of how percolation must work. We can then use

that

to fashion a strategy for creative projects. And creative is the key word here. By our definition, percolation is for building something that was not there before, whether it’s a term paper, a robot, an orchestral piece, or some other labyrinthine project.

To deconstruct how that building process unfolds, we’ll venture into a branch of science known as social psychology, which seeks to elucidate the dynamics of motivation and goal formation, among other things. Unlike learning scientists, who can test their theories directly (with students, trying to learn), social psychologists depend on simulations of social contexts. Their evidence, then, is more indirect, and we must keep that in mind as we consider their findings. But that evidence, when pieced together, tells a valuable story.

• • •

Berlin in the 1920s was the cultural capital of the West, a convergence of artistic, political, and scientific ideas. The Golden Twenties, the restless period between the wars, saw the rise of German Expressionism, the Bauhaus school of design, and the theater of Bertolt Brecht. Politics was a topic of intense debate. In Moscow, a revolutionary named Vladimir Lenin had formed a confederation of states under a new political philosophy, Marxism; dire economic circumstances across Germany were giving rise to calls for major reforms.

The world of science was tilting on its axis, too. New ideas were

coming quickly, and they were not small ones. An Austrian neurologist named Sigmund Freud had invented a method of guided free association, called psychoanalysis, which appeared to open a window on the human soul. A young physicist in Berlin named Albert Einstein—then director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics—had published his theories of relativity, forever redefining the relationship between space, time, and gravity. Physicists like Max Born and Werner Heisenberg were defining a new method (called quantum mechanics) to understand the basic properties of matter. Anything seemed possible, and one of the young scientists riding this intellectual updraft was a thirty-seven-year-old psychologist at the University of Berlin named Kurt Lewin. Lewin was a star in the emerging field of social psychology, who among other things was working on a theory of behavior, based on how elements of personality—diffidence, say, or aggressive tendencies—played out in different social situations.