Influence: Science and Practice (47 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

A variant of the deadline tactic is much favored by some face-to-face, high-pressure sellers because it carries the ultimate decision deadline: right now. Customers are often told that unless they make an immediate decision to buy, they will have to purchase the item at a higher price later or they will be unable to purchase it at all. A prospective health-club member or automobile buyer might learn that the deal offered by the salesperson is good for that one time only; should the customer leave the premises, the deal is off. One large child-portrait photography company urges parents to buy as many poses and copies as they can afford because “stocking limitations force us to burn the unsold pictures of your children within 24 hours.” A door-to-door magazine solicitor might say that salespeople are in the customer’s area for just a day; after that, they, and the customer’s chance to buy their magazine package, will be long gone. A home vacuum cleaner operation I infiltrated instructed its sales trainees to claim that, “I have so many other people to see that I have the time to visit a family only once. It’s company policy that even if you decide later that you want this machine, I can’t come back and sell it to you.” This, of course, is nonsense; the company and its representatives are in the business of making sales, and any customer who called for another visit would be accommodated gladly. As the company sales manager impressed on his trainees, the true purpose of the “can’t come back” claim has nothing to do with reducing overburdened sales schedules. It is to “keep the prospects from taking the time to think the deal over by scaring them into believing they can’t have it later, which makes them want it now.” (See

Figure 7.1

on page 204.)

Psychological Reactance

The evidence, then, is clear. Compliance practitioners’ reliance on scarcity as a weapon of influence is frequent, wide-ranging, systematic, and diverse. Whenever this is the case with a weapon of influence, we can be assured that the principle involved has notable power in directing human action. With the scarcity principle, that power comes from two major sources. The first is familiar. Like the other weapons of influence, the scarcity principle trades on our weakness for shortcuts.

Figure 7.1

The Scarcity Scam

Note how the scarcity principle was employed during the second and third phone calls to cause Mr. Gulban to “buy quickly without thinking too much about it.”

Click, Blur

.

The weakness is, as before, an

enlightened

one. We know that the things that are difficult to get are typically better than those that are easy to get (Lynn, 1989). As such, we can often use an item’s availability to help us quickly and correctly decide on its quality. Thus, one reason for the potency of the scarcity principle is that, by following it, we are usually and efficiently right (McKenzie & Chase, in press).

1

In addition, there is a unique, secondary source of power within the scarcity principle: As

opportunities become less available, we lose freedoms. And we

hate

to lose the freedoms we already have. This desire to preserve our established prerogatives is the centerpiece of psychological reactance theory, developed by psychologist Jack Brehm to explain the human response to diminishing personal control (J. W. Brehm, 1966; Burgoon et al., 2002). According to the theory, whenever free choice is limited or threatened, the need to retain our freedoms makes us want them (as well as the goods and services associated with them) significantly more than before. Therefore, when increasing scarcity—or anything else—interferes with our prior access to some item, we will

react against

the interference by wanting and trying to possess the item more than we did before.

1

So ingrained is the belief that what’s scarce is valuable that we have come to believe its obverse as well—that what’s valuable is scarce (Dai et al., 2008).

Don’t Wait!

Last chance to read this now before you turn the page.

As simple as the kernel of the theory seems, its shoots and roots curl extensively through much of the social environment. From the garden of young love to the jungle of armed revolution to the fruits of the marketplace, impressive amounts of our behavior can be explained by examining the tendrils of psychological reactance. Before beginning such an examination, though, it would be helpful to determine when people first show the desire to fight against restrictions of their freedoms.

Child psychologists have traced the tendency back to the age of 2—a time identified as a problem by parents and widely known to them as “the terrible twos.” Most parents attest to seeing more contrary behavior in their children around this period. Two-year-olds seem masters of the art of resistance to outside pressure, especially from their parents. Tell them one thing, they do the opposite; give them one toy, they want another; pick them up against their will, they wriggle and squirm to be put down; put them down against their will, they claw and struggle to be carried.

One Virginia-based study nicely captured the style of terrible twos among boys who averaged 24 months in age (S. S. Brehm & Weintraub, 1977). The boys

accompanied their mothers into a room containing two equally attractive toys. The toys were always arranged so that one stood next to a transparent Plexiglas barrier and the other stood behind the barrier. For some of the boys, the Plexiglas sheet was only a foot high—forming no real barrier to the toy behind it, since the boys could easily reach over the top. For the other boys, however, the Plexiglas was 2 feet high, effectively blocking their access to one toy unless they went around the barrier. The researchers wanted to see how quickly the toddlers would make contact with the toys under these conditions. Their findings were clear. When the barrier was too short to restrict access to the toy behind it, the boys showed no special preference for either of the toys; on the average, the toy next to the barrier was touched just as quickly as the one behind it. When the barrier was high enough to be a true obstacle, however, the boys went directly to the obstructed toy, making contact with it three times faster than with the unobstructed toy. In all, the boys in this study demonstrated the classic terrible-twos response to a limitation of their freedom: outright defiance.

2

2

Two-year-old girls in this study did not show the same resistant response to the large barrier as did the boys. Another study suggested this to be the case not because girls don’t oppose attempts to limit their freedoms. Instead, it appears that they are primarily reactant to restrictions that come from other persons rather than from physical barriers (S. S. Brehm, 1981).

Why should psychological reactance emerge at the age of 2? Perhaps the answer has to do with a crucial change that most children go through about this time. It is then that they first come to a recognition of themselves as individuals (Howe, 2003). No longer do they view themselves as mere extensions of the social milieu but rather as identifiable, singular, and separate beings. This developing concept of autonomy brings naturally with it the concept of freedom. An independent being is one with choices; a child with the newfound realization that he or she is such a being will want to explore the length and breadth of the options. Perhaps we should be neither surprised nor distressed, then, when our 2-year-olds strain incessantly against our will. They have come to a recent and exhilarating perspective of themselves: they are freestanding human entities. Vital questions of choice, rights, and control now need to be asked and answered within their small minds. The tendency to fight for every liberty and against every restriction might be best understood, then, as a quest for information. By testing severely the limits of their freedoms (and, coincidentally, the patience of their parents), the children are discovering where in their worlds they can expect to be controlled and where to be in control. As we will see later, it is the wise parent who provides highly consistent information.

Adult Reactance: Love, Guns, and Suds

Although the terrible twos may be the most noticeable age of psychological reactance, we show the strong tendency to react against restrictions on our freedoms of action throughout our lives. One other age does stand out, however, as a time when this tendency takes an especially rebellious form: the teenage years. An enlightened

neighbor once advised me, “If you really want to get something done, you’ve got three options: do it yourself, pay top dollar, or forbid your teenagers to do it.” Like the twos, this period is characterized by an emerging sense of individuality. For teenagers, the emergence is out of the role of child, with all of its attendant parental control, and toward the role of adult, with all of its attendant rights and duties. Not surprisingly, adolescents tend to focus less on the duties than on the rights they feel they have as young adults. Not surprisingly, again, imposing traditional parental authority at these times is often counterproductive; teenagers will sneak, scheme, and fight to resist such attempts at control.

Nothing illustrates the boomerang quality of parental pressure on adolescent behavior quite so clearly as a phenomenon known as the “Romeo and Juliet effect.” As we know, Romeo Montague and Juliet Capulet were the ill-fated Shakespearean characters whose love was doomed by a feud between their families. Defying all parental attempts to keep them apart, the teenagers won a lasting union in their tragic act of twin suicide, an ultimate assertion of free will.

The intensity of the couple’s feelings and actions has always been a source of wonderment and puzzlement to observers of the play. How could such inordinate devotion develop so quickly in a pair so young? A romantic might suggest rare and perfect love. A social scientist, though, might point to the role of parental interference and the psychological reactance it can produce. Perhaps the passion of Romeo and Juliet was not initially so consuming that it transcended the extensive barriers erected by the families. Perhaps, instead, it was fueled to a white heat by the placement of those barriers. Could it be that had the youngsters been left to their own

devices, their inflamed devotion would have amounted to no more than a flicker of puppy love?

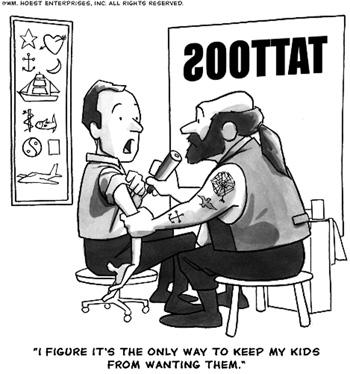

Anticipating a Future Need(le)

© 2008. Reprinted Courtesy of Bunny Hoest and Parade Magazine.

Because the story is a work of fiction, such questions are, of course, hypothetical and any answer to them speculative. However, it is possible to ask and answer with more certainty similar questions about modern-day Romeos and Juliets. Do couples suffering parental interference react by committing themselves more firmly to the partnership and falling more deeply in love? According to a study done with 140 Colorado teenage couples, that is exactly what they do. The researchers in this study found that although parental interference was linked to some problems in the relationship—the partners viewed one another more critically and reported a greater number of negative behaviors in the other—that interference also made the pair feel greater love for each other and desire for marriage. During the course of the study, as parental interference intensified, so did the love experience. When the interference weakened, romantic feelings actually cooled (Driscoll, Davis, & Lipetz, 1972).

3