It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War (4 page)

Read It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War Online

Authors: Lynsey Addario

CHAPTER 1

No Second Chances in New York

My oldest sister, Lauren, likes to tell a story about me. One summer day our entire family was in our backyard pool. I was only a year and a half old and couldn’t swim, so I was standing on my father’s shoulders. My three older sisters and my mother splashed around us. Suddenly, without a word, I bent my knees and jumped into the water. My sisters were stunned. My father said he let me go because he knew I would be fine. When I emerged from the water, I was smiling.

The Addario house in Westport, Connecticut, was a kaleidoscope of transvestites and Village People look-alikes, a haven for people who weren’t accepted elsewhere. My parents, Phillip and Camille, both hairdressers, ran a successful salon called Phillip Coiffures, and they often brought home their employees and clients and friends. Crazy Rose, a manic-depressive former employee, spent most days chain-smoking, spewing non sequiturs. Veto, an openly gay Mexican—rare in the late seventies—solicited show-tune requests from my sisters and banged them out on the living room piano. When my sisters and I came home from school, we were frequently greeted by Frank, known to us as Auntie Dax, dressed as a woman and wearing a feather boa. In the summer my parents brought in two DJs from Long Island to spin Donna Summer and the Bee Gees records. Hors d’oeuvres, Bloody Marys, and bottles of wine were passed around poolside, as were quaaludes, marijuana, and cocaine. Uncle Phil, a scowl on his face, sometimes appeared in a wedding gown for a mock ceremony on the lawn. No one ever seemed to leave. It never occurred to me that any of this was strange, because that was just how our house was.

Family portrait, circa 1976.

We were four sisters—Lauren, Lisa, Lesley, and I—and only two to three years apart in age. I was the youngest and relied on Daphne, our beloved Jamaican nanny, to rescue me when Lisa and Lesley beat me up or stuck puffy stickers up my nose. Our house was rambling and lawless. On a typical day ten to fifteen teenage girls were running around the yard, raiding the never-ending supply of junk food in the kitchen cupboards, skinny-dipping in the pool, and leaving wet towels and underwear along the deck and in the grass. All down the street you could hear us squealing as we pulled our bathing suits up high, rubbed Johnson’s baby oil on our butts, and shot down the big blue slide.

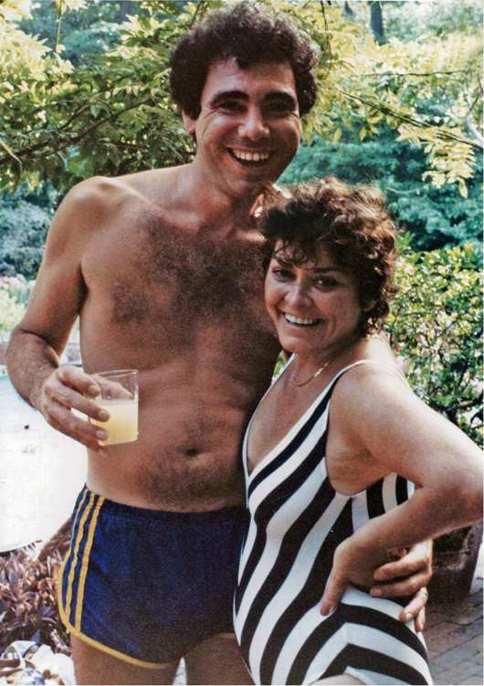

Phillip and Camille at one of the pool parties.

My mother and father were a sun-kissed and smiling team. I never heard them raise their voices, especially at each other. My father, towering over her at six foot one, called my mother “doll.” She was always befriending someone, taking someone under her wing. On Westport’s Main Street we couldn’t walk five feet without one of their clients stopping us, looking me in the eye as if I had a clue who they were. “You’ve gotten so big. I’ve known you since you were this high,” they’d say, gesturing to their knees. All of Westport watched me grow up through my mother’s stories. Every day someone told me what a

wooooonderful

mother I had.

My father was quieter, an introvert who would speak to one person for hours—if he was forced to speak to anyone at all. He spent most of his time out in his rose garden—one hundred bushes of more than twenty-five species of roses—or in his two-story greenhouse, full of ferns, birds-of-paradise, jasmine, camellias, gardenias, and orchids. When I wanted to find him, I followed the long garden hose to the puddles of water that collected around the drains on the greenhouse’s redbrick floor.

I never realized how much work his flowers required, because they made him so happy. Even before a ten-hour day of cutting hair, he spent the wee hours of dawn in his greenhouse, tending to his plants as if each one were a small child. When I watched him, I tried to understand what about these plants captivated his attention. He would lead me through the labyrinth of gigantic pots and show me the mini mandarin tree that always bore succulent fruits, or the orchids that blossomed from seedlings he had ordered from Asia and South America. He grew them off slabs of bark, as they grew in their native rain forests.

“This is a

Strelitzia reginae,

also known as a bird-of-paradise,” he’d say. “And this is a

Gelsemium sempervirens,

a Carolina jasmine, and a

Paphiopedilum fairrieanum,

a lady’s slipper orchid.”

The names were long, an endless stream of vowels and consonants that I didn’t understand. But I was in awe of his knowledge of something so foreign, curious why this exhausting work brought him such mysterious joy.

• • •

O

N

S

EPTEMBER 27,1982

—when I was eight years old—my mother piled my three sisters and me into our station wagon, drove us to the parking lot of the hair salon, and turned off the engine. She must have chosen the parking lot of the salon because it was her second home, and neutral ground for her and my dad. “Your father went to New York with Bruce,” she said. “He is not coming back.”

He was coming out.

Bruce, a manager in the design department at Bloomingdale’s, was one of the many men who hung around our house when I was growing up. One afternoon my mother went to Bloomingdale’s in search of someone to design shades for my father’s greenhouse. Bruce went home with her in her two-seater Mercedes to see the greenhouse and walked in on a typical afternoon at the Addario house: several pots of food on the stove, and family and friends lounging about, talking and laughing loudly. He felt the warmth of our house immediately. “Oh, my God!” he cried. “What a beautiful house!”

Bruce grew up in an icy family in Terre Haute, Indiana, and he was enthralled by the Italian-style camaraderie of ours. He was charismatic, talented, and very flamboyant, and he and my mother became fast friends. They ran around together, shopping and socializing, as if my father didn’t exist. My parents sent Bruce to hairdressing school to become a colorist and gave him a place to stay in our house when he didn’t want to commute back to his apartment in New York. For four years Bruce was part of the family.

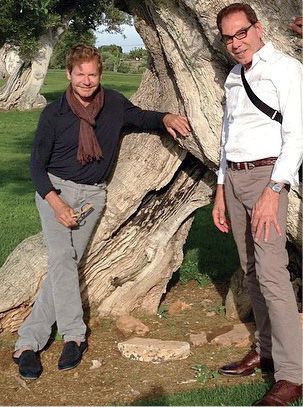

It wasn’t until 1978 that my father made a pass while he and Bruce were running an errand for my mother. The affair went on for a few years before my dad was able to admit to himself that he had fallen in love. My father had suppressed his homosexuality since his teenage years. His mother, Nina, had come to Ellis Island in 1921 along with thousands of other Italian immigrants. They brought their prejudices and conservative Catholic views with them. In the 1950s and 1960s homosexuality was considered a mental illness and was against the law. To this day my father thinks his mother would have committed him to an asylum had he come out back then. When he finally mustered the courage to tell her he was in love with Bruce, she said, “Can’t you just make believe you’re straight?”

I was too young to fully understand why my father was leaving. It was something we deduced on our own or learned at school. “Phillip Coiffures . . . gay . . . their dad is gay” we heard kids whispering in the halls. I don’t remember the women in our family ever having a conversation about my father being homosexual. We only seemed to talk about everyone else’s lives.

We visited Dad and Bruce on weekends in their new home at the end of a half-mile path by the beach in Connecticut. Lauren, the oldest of us girls, was overwhelmed by a sense of betrayal. Two years later she finished high school and left to study abroad in England. Lisa, Lesley, and I bonded together. For the next fifteen years my father seemed to vanish from our everyday life. I reached most early milestones without him.

My mother filled in the gaps: Between clients, she came to all my high school softball games, rewarded me with admiration when I brought home A’s from school, and counseled me on my first love. My mother was infinitely resilient—a trait she learned from her own mother, Nonnie, who’d raised five children on her own—and she tried to stay strong and positive about my father. She kept repeating the mantra they had always told us—“Do what makes you happy, and you will be successful in life”—as if to discourage any negative feelings about him, as if nothing had changed. Perhaps it was the way my mother portrayed their separation, or perhaps it was because I’d grown up my whole life witnessing the sorrow of outcasts, but I accepted that my father had found the happiness he’d longed for. I even found solace in the idea that my dad left my mother for a man rather than a woman.

The weekend parties came to an end. My father stayed in business with my mother for moral and financial support for years after he left to be with Bruce, but the strain of remaining in business together was difficult for everyone. Six years after my father left, he and Bruce opened a new salon; most of my mother’s stylists and clients followed them. She struggled to keep the shop going. Managing money was never my mother’s strength, and without my father she could no longer maintain our expensive lifestyle. The first casualty was the two-seater Mercedes. She was unable to pay the bills on our house and our cars. Almost every month either the electricity or the water was cut off, or the repo man came in the middle of the night to take our car away. In middle school I often looked out the window at daybreak to see if our car was still in the driveway.

We moved out of the house with so many memories on North Ridge Road and moved into a smaller house a few miles away. There was no swimming pool and no big backyard. My three sisters had all moved on to start their lives, and my mom and I were alone.

It was around that time, when I was thirteen, on one of my rare weekend visits to his house, that my father gave me my first camera. It was a Nikon FG, which had been given to him by a client. The gift happened by chance: I saw it, I asked about it, and he casually handed it over. I was fascinated by the science of the camera, the way light and the shutter could freeze a moment in time. I taught myself the basics from an old “how to photograph in black-and-white” manual with an Ansel Adams picture of Yosemite National Park on the cover. With rolls of black-and-white film, long exposures, and no tripod, I sat on the roof and tried to shoot the moon. I was too shy to turn my camera on people, so I photographed flowers, cemeteries, peopleless landscapes. One day a friend of my mother’s, a professional photographer, invited me to her darkroom and taught me how to develop and print film. I watched with wonder as the still lifes of tulips and tombstones twinkled onto the page. It was like magic.

Bruce and Phillip.

I photographed obsessively, continuing when I went off to the University of Wisconsin−Madison, where I majored in international relations. Still, I never dreamed of making photography a career. I thought photographers were flaky, trust-fund kids without ambition, and I didn’t want to be one of those people.

Then I spent a year abroad, studying economics and political science at the University of Bologna. Free from the academic and social demands of Wisconsin, I embraced street photography. Between lectures I photographed Bologna’s arches and ancient nooks with my Nikon. During holiday breaks, I teamed up with new, instantly intimate friends, the kind who typified a college year abroad, and went backpacking around Europe, photographing the ruddy cheeks of Prague and the nude thermal baths of Budapest, the coast of Spain and the crowded streets of Sicily. I soaked up the architecture and the art I had read about my entire life, went to museums and photo exhibitions. I saw a Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective, from when he first began photographing until his death, and for hours I sat and studied his composition and use of light. I was inspired to photograph more.