Jellied Eels and Zeppelins (12 page)

Ethel’s nephews at the peace tea

Jews and Views

‘I always thought what an awful thing it was how Hitler treated those poor Jews - it was wicked and they were the nicest people you could meet. They were lovely people. All those that I ever came across treated you fairly and were very generous. They ran a lot of businesses down our High Street.

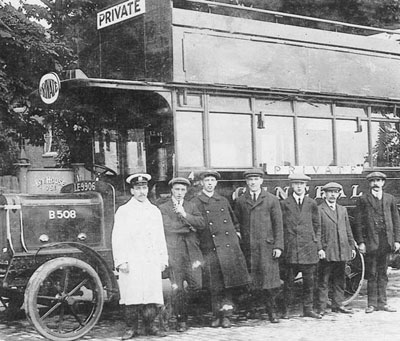

Before the Second World War, my Dad’s middle brother, Fred, used to work for the General Bus Company in Hoe Street - he used to drive the buses. When he was made redundant, he was out of work for some time and he had two boys. He couldn’t get any work, so his wife turned him out and he went to London and strolled around for months and months - my Dad never knew where he was.

Well, what happened, he was going down Petticoat Lane and ‘e never ‘ad a penny in his pocket and it was pouring with rain. He was watching a Jew organise boots and shoes on his stall. He had been standing on the corner all the morning and I suppose he was tired and had got nowhere to sleep. At lunchtime, the Jew called over to him ‘Hello mate! Could you look after my stall for me? I’ll trust yer. I’ll be back in an hour.’ So of course, Uncle Fred looked after the stall and, when the stallholder came back, he gave him some money and said ‘Here you are mate. Go and get yourself a decent meal and then come back to help me,’ which Uncle Fred did.

Uncle Fred (2nd from right) standing in front of an old general bus

And that man took ‘im home, fed ‘im, clothed ‘im, found ‘im a flat and found ‘im some furniture. Uncle Fred worked for that man and lived in that flat right up until he died.

The King and Queen in the Second World War were pretty good. She was always around people when they lost their homes; and the family decided to stay in London despite the bombs. I thought she was a lovely queen. About the best one we’ve ever ‘ad, though the Queen Elizabeth we have now has done very well. Her mother thought a lot of George VI. He didn’t seem to do a lot, but she used to support him, ‘cos he was a nervous type and used to stutter a lot. Wonderful woman, she was. She done well in her lifetime.

Regarding the abdication of Edward VIII, I thought the way he carried on with Wallis Simpson was awful. I mean - he knew what she was like. She’d already been married twice. And he abdicated because of her. He did what he thought was right, because he thought such a lot of her. But, if she thought she was going to be Queen, she was unlucky. I didn’t have any sympathies with her.

I think that going through what we did during the Second World War, probably did make me a bit shell-shocked to a certain extent. I mean, we lost thousands and thousands of people and they never told us how many thousands were lost in and around London. All those who were lost in bombed houses and were never recovered - thousands of people. (

According to records, there were 301 fatalities and 2,833 people injured in Walthamstow during World War II. In London, 29,890 people lost their lives. Many more of course had their homes and possessions destroyed.

)

But I think that my experiences during the war have made me a better person, ‘cos it makes you realise what can happen and not to take anything for granted. And you had to make do with what you could get and make do and mend. We always tried to get a decent dinner, no matter what.’

1945-2003

Twenty

Pinks, Pails, Bricks and Nails

Ethel had reached her mid 30’s by the time the war ended. She and Joe remained childless throughout their married life. Though Ethel would have loved children, Joe did not want any:

‘His mother warned me that he didn’t want children, but I told her ‘Oh, I expect he’ll have one with me, ‘cos I love ‘em!’ In his latter years, he would say ‘Oh, I wish I had a son to help me,’ but I said ‘Well, that’s your fault!’ My friend’s breakdown after losing her baby shortly after birth during the Second World War - that’s what turned my chap off from wanting children, I’m sure of that.’

Instead, the couple directed their energies into trying to obtain building permission for their land in Doddinghurst, which Joe had earlier partly inherited from his parents:

‘Joe’s Dad had been pensioned off in the 1920’s - he had been a stoker for the electricity company - so he used his money to buy the land in Doddinghurst. It wasn’t quite enough, so Joe would travel by motor bike once a month to Billericay to pay off the rest out of his own money.

Joe’s Dad would come to Doddinghurst now and again to escape for the weekend, and he would stay in the shed on the land. It used to cost him a shilling to travel by coach from Leytonstone to Brentwood. He would grow flowers on his plot - lovely pinks, which smelt like cloves - and would tie bunches of them onto a broomstick and sell them to the passengers on the coach on the way home to recuperate his bus fare.

Ethel Elvin on Doddinghurst land. Winter 1940

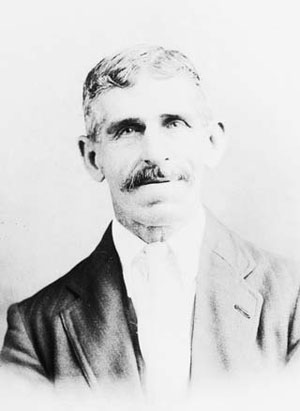

Joe’s father

Joe started up his own business after the war. He’d had a dispute with Ensign about a camera lens, so Joe said ‘Thanks very much, I’m leaving.’

He’d been doing some private repair work for Wallace Heaton in Bond Street, London, and also for Dolland and Aitchinson and Newcombes. He had a chat with another chap called Harry, who worked there, and the pair of them started up on their own. E.W. Repairs began in the back bedroom of our little flat in Walthamstow. Then we heard about an empty shop in Leytonstone from Joe’s brother, so we put all the shelves in for storage and they set up in there. We hadn’t yet started work on our house in Doddinghurst.

I’d learnt some typing at evening classes, so I got a photography magazine, took down all the names and addresses of companies and sent out some letters. They got a lot of work. I did all the typing and mailing for them and all their accounts once a month, sitting up until the early hours. And I never got paid a penny - Joe said that I should do it for love!

Every Saturday, after Wallace Heaton had telephoned me with a list of cameras, I would take the repaired items to Bond Street in a carrier bag. Although we had insurance for the cameras just in case they got stolen, I thought that the cameras would be more conspicuous if I’d taken them in a box.

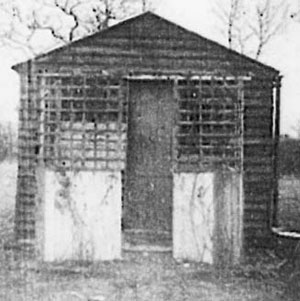

The hut in Doddinghurst, where Ethel and Joe lived while building their house

It took us five years to get planning permission for our house. I used to do all the writing and everything and I got on to the House of Commons and got the water laid on. Because of the war, building was very restricted. We finally obtained permission in 1950 and it took us about another ten years to complete the house, because we kept running out of money. They said that we could start building once we lived down here and had got permission to put on the water. By then we’d exchanged our rented flat in Roberts Road with a lady, who sold us her house in Higham Hill Road. We sold that for a profit and never had no mortgage. The money from that helped to fund some of the building of our house. Then we had to wait until we had a bit more money to finish it.

Mum and Dad bought the bungalow next door and we lived in that for a few months until they moved in. We stored our furniture and then we lived in a hut on the land for two years while we built the first two rooms. We lived in those until we finished the rest of the house.

Joe would work on the house during the day and on the cameras at night, sitting in the shed. When the building was completed, he gave up his camera work.

Living in the hut was absolutely freezing during the winter months. We had no running water to start with (

although the couple had earlier received permission to put in a water main, they were unable to do so until their property had been built

), so we used to have to carry it back from the large well up the lane in two pails swinging from a yoke across our shoulders. Then Joe managed to dig our own well, which is 32 feet deep. The water in that well has only ever dried up once. That was in the drought of 1976.

One Sunday afternoon, the church bells were ringing when Timmy, the cat, frightened one of our chickens. It flew down the well and we had to pull it out with the bucket. We changed the words of the nursery rhyme ‘Ding Dong Bell’ to ‘Ding dong bell, chicken’s down the well; who put him in? A cat named Tim!’

We eventually had the water laid on to the property on 24th June 1954. But we had a Jap engine generator for the electricity.

In the shed, we had a little kitchenette at the back and a little put-you-up bed and then a little stove with a chimney sticking out over the brook. We used to take every drop of water out of the well and boil it all up for a bath. We had a screen that we’d put around us and my chap would sit in the armchair while I had my bath, then we used to pull the screen back, tip the water out in the brook and do it all over again. We both had a bath once a week.

We did a good job building this house - just the two of us with our own hands, though someone did help for a while on the porch. The house has never moved in any way whatsoever. When we’d done the structure, I sat in the front room before we had any windows in, with a little iron block and straightened all the bent nails out, ‘cos we couldn’t afford any new ones - it took me hours. Dad had showed me how to paper a room when I was 17, but I never told Joe in case he got me to paper all the walls too! Joe made a wooden block and we made all the bricks with sifted ash and cement. And my husband was a wonderful plasterer. There were papers for the brickwork, the woodwork, the roof and every part of the building that you finished had to be checked. I had a pile of papers.