Language Arts (41 page)

Authors: Stephanie Kallos

“Dana is at Children's Hospital,” she continued, “and I'm sure he'd love to see you, before . . .” She started to cry again.

Before he dies,

Charles thought.

She stood, removed her glasses, pressed her palms against her eyesâCharles saw then that, though tiny, she had the long-boned, elegant fingers of a much taller person. Dana had inherited his hands from her.

“You have been such a wonderful friend, Charles,” she said. “All this year.”

“Here you are, Mrs. McGucken,” one of the office ladies said, sliding a small sack across the counter.

“Thank you,” she said, with the slightest hint of coldness. Then she looked down and stroked the side of Charles's face; her hands had the feel of warm silk. “Goodbye, Charles.” She briefly cupped his chin, smiled, and was gone.

Even after she passed through the office door and out of view, Charles could somehow still see her, a shimmering remnant of embodied sorrow.

“Can I help you, Charles?” the school secretary asked.

“Charles?” the nurse said, emerging from the Quiet Room. “Are you all right?”

He took off running: out the door, across the playground, up Meridian to 145th, across the freeway bridge, right on 15th, down the hill, and into the sanctuary, where the pews of St. Matthew's were empty.

He stood in the foyer, catching his breath. Now that he was there, he wasn't sure what to do.

Light a candle? People sometimes did that when they came to church.

Pray? He'd only ever said prayers in his room at bedtime or in church on Sunday. It had never occurred to him that the need for prayer could strike at any time. Would God show up at this unaccustomed hour, and for a solitary ten-year-old child? It seemed unlikely. Still, assuming it couldn't hurt, he whispered the Lord's Prayer and then,

Please God, please don't let Dana McGucken di

e.

He waited.

Perhaps the keyâas with handwriting practiceâwas repetition.

Please God, please don't let Dana McGucken die, please God, please don't let Dana McGucken die, please God, please don't let Dana McGucken die, please God . . .

After a while, the words seemed to gain density but lose potency, overfilling the space, crowding God out. Was there no other way?

In the back of the sanctuary was a notebook, an ordinary three-ring binder filled with lined paper. Charles had seen his mother write something inside it once, one Sunday morning when she didn't have the flu. He opened it.

There were all kinds of prayers in there, all kinds of handwriting . . .

Please God, look after my family, especially my father, who is suffering so much . . .

Please God, teach me to be a better mother to my children . . .

Please God, help my husband stop drinking . . .

Please God, watch over and protect my son . . .

Please God, heal my daughter . . .

Please God . . .

Please . . .

Maybe

writing

his prayer would make it more likely to be heard and answered, so he picked up the pen.

But something was wrong. He could not make his hand obey.

Again and again he tried to write his prayer for Dana; again and again, he failed.

â¢â¦â¢

Hours later, when the St. Matthew's priest began to prepare for evening Mass, he discovered a boy with a tearstained face fast asleep on the floor in the back of the sanctuary. He was clutching the book of prayer intentions.

Gently, carefully, the priest extracted the binder from the boy's grasp.

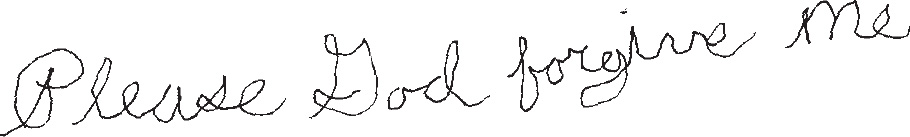

Inside, he found page after page of writing, a collapsed mess, a chaos of scrawled, angular, graceless lines, the same words over and over again, just barely legible:

When Mrs. McGucken answered the door, Charles couldn't bring himself to linger on her face; instead, his eyes immediately went to a large window on the wall opposite. It had been fitted with a system of floor-to-ceiling glass shelves that were entirely given over to dozens of small pots of variously colored flowers.

“Charles,” she said, “Charles Marlow. Thank you so much for coming.”

The flowers did not obscure what little light came into the roomâCharles determined it to be north-facingâbut rather filtered it in a lovely way, the backlit petals and velvety leaves glowing, small snatches of color that gave the effect of intricate stained glass.

“I've made coffee, but I also have hot water for tea if you'd prefer,” she said.

“Coffee would be perfect,” Charles said.

“Please, sit down.”

There were three rooms from what Charles could tell: this oneâserving as a combination living/kitchen/eating areaâa bathroom, and (presumably) a bedroom behind a partial wall. Charles couldn't help it; he found himself looking for evidence of Dana, but there was none. The bookcase held only books. With the exception of two large colorful framed art prints, the walls were bare.

“Do you take cream and sugar?” she asked.

“Black would be fine.”

Foss Home was on Greenwood Avenue in North Seattle; it was Lutheran-run, as were many assisted-living facilities, something Charles had learned when he moved his mother back to Seattle from Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, after the death of her second husband, a sweet, uncomplicated, retired Jewish grocer named Leo with whom she'd been very happy. Garrett Marlow experienced neither a second marriage nor a happy ending; he died at forty-eight, two years after the divorce, in a car accident.

“Here you are, Charles.”

“Thank you,” he said. “I cannot stop staring at those flowers.”

“Oh, yes,” Mrs. McGucken said. “My violets . . . they do keep me busy . . .”

Charles followed her over to the window and was treated to an impromptu lecture on the joys of

Saintpaulia ionantha.

Mrs. McGucken identified each distinct plant variety and spoke about their soil and light requirements, emphasizing that although African violets had a reputation for being horticultural prima donnas, it was completely undeserved; they were, in fact,

easy

to growâcertainly less high-maintenance than

orchids.

They were also long-lived (some of her specimens were decades old), and, perhaps best of all, their diminutive size made them perfect for small, dimly lit dwellings such as this.

She was obviously an expert, but Charles had the sense that the subject of flowers wasn't a source of pride for Mrs. McGucken so much as a way of initiating a conversation with someone she hadn't seen for fifty years. It had taken all his courage to come. Possibly, inviting him had taken all of hers.

“You've converted me,” Charles said as she concluded her lecture, eliciting from Mrs. McGucken the most delightful and surprising response: a low-pitched, throaty chuckle.

“I so enjoyed that article in the newspaper,” she said, leading Charles to the sofa and settling herself in a nearby chair.

They went on to chat about all the expected, safe topics. At Mrs. McGucken's urging, Charles talked about his long history as a City Prana teacher, his students, this year's impressive slate of senior-project advisees. Mrs. McGucken filled in the details of what sounded like a very busy life, especially for someone who had to be in her eighties: her volunteering obligations at the nearby elementary school and the public library, her active membership in a society of fellow African violet enthusiasts.

About forty-five minutes into their visit, she got up to pour them each another cup of coffee and then said, “Come.”

Charles followed her around the partial wall; on the other side, as he'd expected, was Mrs. McGucken's bedroom. What he hadn't expected were the photographs; in this private area of her tiny apartment, the walls were covered with them.

“I don't like to talk about him with everyone,” she said by way of explanation, “so I keep these out of sight. Please, look.”

Charles immediately recognized Dana in baby pictures, as a toddler, and of course at elementary-school age, but thenâ

it couldn't be

âthere were pictures of Dana as an adolescent, a teenager, a young man.

“What is it, Charles? Are you all right?”

“These pictures,” he said, pointing. “Is this . . . ?”

“Yes, that's Dana. He must be, oh, maybe twelve or thirteen in that one.”

“But I thought . . . I thought . . .”

“Charles. Sit down, please. You've gone quite pale. Let me get you something.”

Charles sank onto the bed, staring. It

was

Dana, without question: older, grown far past the age Charles had continued to imagine him for almost fifty years, but still, the same face, the same radiance, the same white suit in gradually larger sizes.

“Here,” Mrs. McGucken said, returning with a glass of water.

“I thought . . . ,” Charles began again, but his mouth was parched; he had to take a drink before he was able to go on. “After what happened on the playground . . . when I saw you in the office that day and you told me he was in the hospital . . . I just thought . . .”

“You thought he'd died? Oh, no, Charles, I'm so sorry.” She placed one of her hands over his. “No. No, dear, Dana recovered from those injuries. He had a severe infection, and it was touch-and-go for a while, but . . . I thought you knew. I called your mother to tell her, in case you were worried.”

“You told my mother?”

“Yes, Iâ”

“You told my mother that Dana was all right.”

“Yes. I'm sorry, Charles. I'm really so very sorry that you didn't know. I kept Dana at home for a while after what happened, but then a school opened up on Shaw Island, a school for special children run by an order of Benedictine nuns. Dana lived there until he was eighteenâthose were very good years for him; here's a picture of him thereâand then he moved back in with me.”

In the photo, Dana looked to be about sixteen. He was sitting at a picnic table next to a nun. She was writing; he was watching. In the far distance was an expansive view of undulating pastures dotted with grazing sheep; in the midground, a plain wooden structure, the schoolhouse, perhaps; on the porch, another nun was helping a young child hold a watering can over a window box filled with flowers.

Charles looked up and began surveying the photos again. It was then that he noticed: there was a certain point after which Dana did not advance in age.

“What happened to him?” he asked.

“He died in 1980, at home. He was twenty-seven years old. The diagnosis was sudden unexplained death in epilepsy. It's not uncommon for children like Dana, who have a history of seizures, to go that way. He died in his sleep, very peacefully, from what I could tell. I didn't hear him cry out that night, and I always did, I always heard him. When I went to rouse him in the morning, as usual, he was gone.”

“I'm so sorry.”

“Oh, don't be. Really. Brief as Dana's life was, it was very rich. He was loved; he had friends.” She gave Charles's hand a gentle pressure. “And as far as what happened at Nellie Goodhue, he seemed to completely recover. It didn't change him in the least. But then, as you might remember, Dana had a great gift for . . . Oh, how can I say this? For

happiness,

you know? He was so utterly himself, so completely at home in his own body and spirit. He was a kind of angel, I think. An angel on earth. At least, he was in my life.”

She reached up and rubbed the tears from her eyes, temporarily displacing those large, black-rimmed eyeglasses Charles remembered so clearly.

“Here,” she said. “I have something for you.” She opened a bureau drawer and brought out a framed photograph: their fourth-grade class picture. “That's yours to keep. I had a copy made. I thought you might like it.”

An objective observer would give the photograph no special weight except as documentary evidence of 1960s fashion and haircuts. But to Charles, the photo was revelatory:

It wasn't him who occupied the choice position in that photograph, the place that, in the 1960s, was always given to the teacher's pet. Nor was it the brilliant and myopic Astrida Pukis. The person standing next to Brax the Ax and holding her hand was Dana McGucken.

Here too was a window into a possibility that Charles had never considered: in her way, Mrs. Braxton loved Dana.

“I've gone on and on about my family,” Mrs. McGucken said after they returned to the living room. “So rude of me not to ask about yours. Did you marry?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Children?”

There was a story he could tell, about his son and daughter, but instead he nodded and said, “Two. One boy, one girl.”

They talked a while longer, until it became clear that Mrs. McGucken was tiring.

But Charles was tiring too, he realized; there was a strange, weighted feeling in his body, not exactly unpleasant, as if he were a boat that had been filled with water but was now emptying.