Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion (11 page)

Read Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion Online

Authors: Susan Green,Randee Dawn

BOOK: Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion

2.34Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Producer David DeClerque, who works at the New Jersey soundstage, says this about

SVU

’s cross-country relations: “We ship, hopefully, wonderful footage to the West Coast and keep our fingers crossed that they’re happy with it.”

SVU

’s cross-country relations: “We ship, hopefully, wonderful footage to the West Coast and keep our fingers crossed that they’re happy with it.”

He was a New York location manager for features, TV pilots, and movies-of-the week before the Mother Ship appeared on his radar. “I wanted to get into the production managing field,” DeClerque says. “They gave me the opportunity a few times. . . . But there didn’t seem to be a full-time position. In the middle of (

Law & Order

’s) season six, I landed a pilot with

Dellaventura

(CBS, 1997).”

Law & Order

’s) season six, I landed a pilot with

Dellaventura

(CBS, 1997).”

Three years later, friends from

L&O

recommended him to Dick Wolf for the spin-off. “I felt these guys know how to make television shows,” DeClerque says. “They taught me how to do episodic TV.”

L&O

recommended him to Dick Wolf for the spin-off. “I felt these guys know how to make television shows,” DeClerque says. “They taught me how to do episodic TV.”

His

SVU

counterpart is unit production manager and producer Gail Barringer, who began as a production accountant on the show in 1999. “Dave and I alternate (responsibility for) episodes,” she explains. “We both oversee operation of the facility, the crew, and the needs of actors. We report directly to studio executives. We’re in charge of budgets and amortization. We make deals for crew, equipment, purchase orders. We oversee studio policies and procedures.”

SVU

counterpart is unit production manager and producer Gail Barringer, who began as a production accountant on the show in 1999. “Dave and I alternate (responsibility for) episodes,” she explains. “We both oversee operation of the facility, the crew, and the needs of actors. We report directly to studio executives. We’re in charge of budgets and amortization. We make deals for crew, equipment, purchase orders. We oversee studio policies and procedures.”

Gail Barringer

Better yet, “I’ll ask them if we can afford to blow up a car.”

Kaboom. Barringer hesitates when asked about the cost per episode. “Well, we’re given a template that the studio allows us to tweak,” she says. “On ‘Lunacy’ (season ten), the special effects budget is over the norm. That happens with stunts, using the Hudson River, a lot of blood. We have no wiggle room this year.”

According to Barringer,

SVU

has approximately twenty-five vehicles, ten to fifteen trucks or trailers. She adds, “Our fleet includes some hybrids. We’ve had to double our fuel budget lately (due to rising fuel costs). We always want to shoot in New York City, even though it’s more expensive than working on our stage. We just happen to be in a facility that costs less than it would in Manhattan.”

SVU

has approximately twenty-five vehicles, ten to fifteen trucks or trailers. She adds, “Our fleet includes some hybrids. We’ve had to double our fuel budget lately (due to rising fuel costs). We always want to shoot in New York City, even though it’s more expensive than working on our stage. We just happen to be in a facility that costs less than it would in Manhattan.”

When the inevitable glitches occur, she may be forced to get tough. “On ‘Doubt’ (season six), which Ted Kotcheff directed, there was a truck in the shot that wouldn’t start,” Barringer recalls. “It was at night and we had a long delay, went really late. It’s the worst feeling to keep looking at your watch. We want it all to be perfect, but your watch just screams at you. There are times when I look at Ted or (episode director) Peter Leto and say, ‘This is your last take. I’m sorry.’”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

TEARS AND LAUGHTER

T

here’s no doubt

SVU

’s tales of human depravity can be disturbing for writers, producers, actors, and crew members. They’ve all searched for ways to coexist with scripts about exceedingly loathsome situations.

here’s no doubt

SVU

’s tales of human depravity can be disturbing for writers, producers, actors, and crew members. They’ve all searched for ways to coexist with scripts about exceedingly loathsome situations.

“It’s tough,” says former co-executive producer Patrick Harbinson. “That’s why I tended to do more of the issue stories. My own shield against depression is to tell a story with social relevance. But sometimes at the start of a new year I’d think: ‘God, not another sex crime.’”

And another and another and another.

“It absolutely does get to you,” acknowledges George Pattison, the director of photography. “You build up a callus, but any human being would be affected.”

Tamara Tunie’s

SVU

medical examiner is awash in body parts and some of the show’s most graphic dialogue. “I think certainly my awareness of the heinous things that one human being can do to another has become keener,” she acknowledges. “But we know it’s pretend while we’re doing it, and when the camera’s not rolling, it’s very much a light feel on the set. It doesn’t get too maudlin or heavy. So there’s a certain part of me that remains able to detach myself when I’m not in it. But at the same time, I’m still affected emotionally, by the reality of humanity against humanity.”

SVU

medical examiner is awash in body parts and some of the show’s most graphic dialogue. “I think certainly my awareness of the heinous things that one human being can do to another has become keener,” she acknowledges. “But we know it’s pretend while we’re doing it, and when the camera’s not rolling, it’s very much a light feel on the set. It doesn’t get too maudlin or heavy. So there’s a certain part of me that remains able to detach myself when I’m not in it. But at the same time, I’m still affected emotionally, by the reality of humanity against humanity.”

With real-world experience, co-executive producer Amanda Green may have a more profound vantage point than do others at

SVU

. “I spent four years working in a maximum-security federal prison, in outpatient settings with all sorts of victim populations, and in domestic violence shelters. . . . Working with HIV positive victims in 1989 when AIDS was a death sentence, I learned that these people were going to die, and were going to die awful, undignified, painful deaths. You have to learn to separate yourself.”

SVU

. “I spent four years working in a maximum-security federal prison, in outpatient settings with all sorts of victim populations, and in domestic violence shelters. . . . Working with HIV positive victims in 1989 when AIDS was a death sentence, I learned that these people were going to die, and were going to die awful, undignified, painful deaths. You have to learn to separate yourself.”

Executive producer Ted Kotcheff knows that nothing presented on

SVU

could ever be as horrific as what cops witness every day in real life, evident in a field trip before the show began. “I went to an actual Manhattan

SVU

and sat there all day long,” he recalls. “Richard Belzer came, as well. We saw some terrible stuff. Two Hispanic women were weeping and a girl of about five or six had a bandaged hand. Her father had been frying bacon as the child was dancing around. He told her to shut up, then burned off all her fingers on the hot stove. How can detectives stand hearing such things?”

SVU

could ever be as horrific as what cops witness every day in real life, evident in a field trip before the show began. “I went to an actual Manhattan

SVU

and sat there all day long,” he recalls. “Richard Belzer came, as well. We saw some terrible stuff. Two Hispanic women were weeping and a girl of about five or six had a bandaged hand. Her father had been frying bacon as the child was dancing around. He told her to shut up, then burned off all her fingers on the hot stove. How can detectives stand hearing such things?”

Some cannot. “The police told us no one can bear the abuse of children,” Kotcheff says. “The job span there is two years. They get out. They can’t take it.”

He cites a second incident that has remained with him (and is the subject of season one’s “Nocturne” episode). “A piano teacher in Harlem had been giving free lessons but for ten years molested kids and videotaped them. . . . Detectives had to watch hours and hours of footage and testify in court. The next day, one guy quit and requested to be transferred back to drug crimes.”

The fictitious

SVU

detectives have been able to keep going for a decade, but not without scarred souls. Green sees it as something of a cause.

SVU

detectives have been able to keep going for a decade, but not without scarred souls. Green sees it as something of a cause.

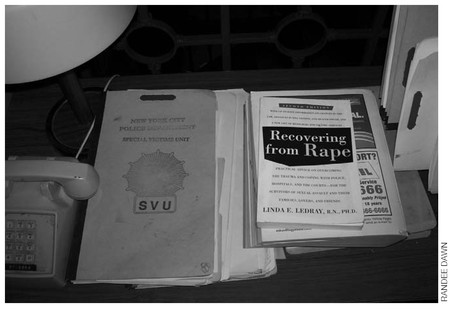

Props from the

SVU

set

SVU

set

“People watch our show and they take the information we present and they act on it,” she suggests.

Years ago, at an event honoring the series, Green met a man who recounted a true story. A young woman had walked into his office to report a rape two weeks after the fact. His reaction: “My face fell, because I knew all the evidence, forensics, the DNA, was all lost.”

When he started to explain to the victim why it would be tough to find the perp without that evidence, she held up a bag that had all her clothes in it from the night of the attack. Nothing had been washed.

“He asked how she knew to do that and she said, ‘I saw it on

SVU

,’” Green explains.

SVU

,’” Green explains.

One of her fellow co-executive producers, Jonathan Greene, discovered much the same path for addressing the human toll of sex crimes. “Everything evolves,” he suggests. “As you learn to do something, you learn how to do it better and better . . . And it was a question of learning how far we could take this. I remember there were a lot of times we’d say, ‘Are we going to be able to come up with enough stories for each season?’ And as it turned out, it wasn’t a matter of finding the stories, because they’re out there, but the question is how can you tell these stories in such a way that they will somehow make a difference?”

One answer has been the fact that Mariska Hargitay (Det. Olivia Benson) started a charitable organization for victims of sex crimes. “Often, she will send the writers emails she will get from victims that say

SVU

helped them realize this or change that,” Greene explains. “It’s one thing to have a great job like this, writing on a show that you not only care about but believe in, where it’s not just a paycheck.”

SVU

helped them realize this or change that,” Greene explains. “It’s one thing to have a great job like this, writing on a show that you not only care about but believe in, where it’s not just a paycheck.”

The same sense of higher purpose apparently is important to actor Richard Belzer. “We’ve all been affected in one way or the other, and have befriended people who do what we do. . . . I’m amazed at some of the victims I’ve met, who maintain their humanity,” he says. “So it’s very moving. It’s not like I’m just doing some stupid cop show.”

Dann Florek (

SVU

’s Capt. Don Cragen) suspects each person working on

SVU

has found a different way to deal with its most wrenching themes. “First of all, you know it’s not real, but it’s based on what is real. . . . Even though you know it’s fake, you’re looking at pictures of a lot of hurt people, and some of them are hurt children. And sometimes those just pop into my head at night. (Or) I’ll see a kid on the street who looks like a kid who was in makeup to look hurt.”

SVU

’s Capt. Don Cragen) suspects each person working on

SVU

has found a different way to deal with its most wrenching themes. “First of all, you know it’s not real, but it’s based on what is real. . . . Even though you know it’s fake, you’re looking at pictures of a lot of hurt people, and some of them are hurt children. And sometimes those just pop into my head at night. (Or) I’ll see a kid on the street who looks like a kid who was in makeup to look hurt.”

Director Peter Leto mugs with a special guest star on the set of season ten’s “Wildlife.”

That burden is lessened for him when he meets people who watch the show with their children “because they feel these are lessons to be learned,” Florek says. “(Episodes) can serve as cautionary terms. The best way I can describe the show is: We shine a light in a very dark place. And I think that’s good. I know we’re entertainment, but we can enlighten.”

Dawn DeNoon found a recipe for staying sane when working on a bleak story with her former writing partner, Lisa Marie Petersen.

“(We) used to do the sitcom version along with it,” says DeNoon, a co-executive producer. “We didn’t write it down, but we’d do the sitcom. We’d say the wacky version, which is hard to do with sex crimes. . . . It’s like what the cops do in real life, their gallows humor. Even in real life they do a lot more than we’re allowed on (

SVU

), because it looks so bad. But there’s no way to deal with it otherwise. If you didn’t find some humor in it, you’d eat a gun.”

SVU

), because it looks so bad. But there’s no way to deal with it otherwise. If you didn’t find some humor in it, you’d eat a gun.”

Comic relief on the written page has been a coping mechanism for DeNoon, as well. She gives an example of patter the detectives would use to lighten the heavy load before a court appearance: “‘Oh, I have to go testify in this weenie-wagger trial.’ They weren’t the hard core cases; they were the sillier cases. You couldn’t do that for a whole episode.”

On the set, wisecracking has been raised to an art form.

One example: On location at a Manhattan park for a scene in “Lunacy” (season ten), episode director Peter Leto describes NBC’s attempt to become more eco-friendly as a “green effort.” Actor Ice-T (Det. Odafin Tutuola) chimes in with: “No trees were harmed in the making of this episode.”

Any personnel experiencing emotional harm from the wretched crimes depicted on

SVU

hopefully can continue to find solace in off-camera levity. “We’re blessed here,” suggests first assistant director Howard McMaster. “It’s extremely rare to have a show without at least four assholes. But this core group of actors likes to cut up and have a good time.”

SVU

hopefully can continue to find solace in off-camera levity. “We’re blessed here,” suggests first assistant director Howard McMaster. “It’s extremely rare to have a show without at least four assholes. But this core group of actors likes to cut up and have a good time.”

Other books

The Serpent of Eridor by Alison Gardiner

The Set Up by Kim Karr

Star Wars: Jedi Prince 2: The Lost City of the Jedi by Paul Davids, Hollace Davids

Druids Sword by Sara Douglass

Dark Road to Darjeeling by Deanna Raybourn

Cain's Darkness by Jenika Snow

Valentine from a Soldier by Makenna Jameison

First Visions by Heather Topham Wood

Rise of the Defender by Le Veque, Kathryn

Festival of Fear by Graham Masterton