Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion (7 page)

Read Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion Online

Authors: Susan Green,Randee Dawn

BOOK: Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion

2.2Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Baer’s reign apparently began to make life on the set, well,

bear

able. “When Neal came, it was an energy shift for the show and everything changed. We owned it, we were inspired, we cared,” Hargitay suggests. “We all had the same vision. Neal brought amazing writers and all of a sudden we got excited. He’s a great leader and accessible. I can get that man on the phone twenty-four hours a day.”

bear

able. “When Neal came, it was an energy shift for the show and everything changed. We owned it, we were inspired, we cared,” Hargitay suggests. “We all had the same vision. Neal brought amazing writers and all of a sudden we got excited. He’s a great leader and accessible. I can get that man on the phone twenty-four hours a day.”

She is comforted by the fact that “Neal has the excitement (level) of a seven-year-old. There’s this beautiful collaboration. Everything started to gel, and then everyone was more invested. It’s so fun to come to work. It all just takes time. It takes time.”

Like Baer, Kotcheff appreciates Hargitay and her fellow thespians. “In my fifty-seven years as a director, some of that on live television, this is the nicest cast I’ve ever been with,” he says. “No vanity, no egos, no bad behavior. They all come to work with energy and enthusiasm and great expectations.”

Such energy and enthusiasm can’t be all that easy to rally. “After these actors spend fourteen hours here,” Kotcheff points out, “they have to go home and memorize six pages of dialogue!”

CHAPTER FOUR

THE GRIND

I

n 2000, the

Law & Order

patriarch explained how he expected his business to function. “I hire obsessive people, people who literally work sixty to seventy hours a week for months on end and who have fine-tuned detectors for what’s good and what’s bad,” Wolf said in an interview with a quarterly magazine published by the Producers Guild of America.

n 2000, the

Law & Order

patriarch explained how he expected his business to function. “I hire obsessive people, people who literally work sixty to seventy hours a week for months on end and who have fine-tuned detectors for what’s good and what’s bad,” Wolf said in an interview with a quarterly magazine published by the Producers Guild of America.

Jonathan Greene, a co-executive producer who has been slogging through

SVU

workdays since season two, observes that there really is no typical daily structure: “It depends on how much time I have for an episode. I’ve had as many as six months and I’ve had as little as two weeks from beginning to end. When I’m researching, it’s talking to people on the phone, it’s reading a book.”

SVU

workdays since season two, observes that there really is no typical daily structure: “It depends on how much time I have for an episode. I’ve had as many as six months and I’ve had as little as two weeks from beginning to end. When I’m researching, it’s talking to people on the phone, it’s reading a book.”

Each with an office, writers are largely left on their own in L.A., though always aware of the looming deadline. While writing the script, schedules become more rigorous. “I’ll generally get up and be in the office as early as five in the morning, no later than six if I can get myself out of bed,” Greene says. “I do my best work in the mornings when I’m fresh. I have this rule: I never hand in work at night until I have time to check it in the morning.”

Jonathan Greene

Despite ubiquitous computers in the Studio City headquarters, many writers find it useful to put their thoughts down on whiteboards before creating “beat sheets” (on which the distinct rhythms of a story are charted) or more advanced drafts.

“There are some people who can write a script without a beat sheet, but I find the more detailed and thought-out our beat sheet is—the outline, if you will—the easier it is to write the script,” Greene suggests. “Because you’ve taken care of all of the thinking. You still have to (invent) great dialogue, but you’ve taken the hard part, which is the story, out of the picture.”

The going isn’t always smooth, of course. “You get to shape it as you go along and, even when you have the best of intentions, you can write yourself into a corner,” he says. “Then, the fun part is, ‘OK, how do I get out of the corner?’ That gets the juices flowing.”

Juice or no juice, writing tends to be a solitary profession. And

SVU

more or less eschews the collective effort—called a “writers’ room,” in which everyone hashes out script ideas—that’s favored by many other TV shows.

SVU

more or less eschews the collective effort—called a “writers’ room,” in which everyone hashes out script ideas—that’s favored by many other TV shows.

Judith McCreary prefers it that way. “In the Dick Wolf camp, you sink or swim on your own versus being in a room with other writers, putting all the beats up on a board as a group. That makes for lazy writing.”

Tara Butters, employed at

SVU

from seasons three through seven along with writing partner Michele Fazekas, says that lack of a writers’ room proved to be liberating: “As a result, there was no sense of competitiveness. We were working on our own, so it was like writing your own mini-feature.”

SVU

from seasons three through seven along with writing partner Michele Fazekas, says that lack of a writers’ room proved to be liberating: “As a result, there was no sense of competitiveness. We were working on our own, so it was like writing your own mini-feature.”

As seen by a newcomer, Mick Betancourt (who joined

SVU

in season nine after working on several other shows), a writers’ room is not always such a terrific idea. “I would have a meeting maybe once a week, which sometimes we do here, just to see where everybody’s at, and have writers write—that’s what they do best,” he says. “If writers had tremendous personalities they wouldn’t like the isolated experience of writing. (Put) five hermits in a room to socialize for fourteen hours?”

SVU

in season nine after working on several other shows), a writers’ room is not always such a terrific idea. “I would have a meeting maybe once a week, which sometimes we do here, just to see where everybody’s at, and have writers write—that’s what they do best,” he says. “If writers had tremendous personalities they wouldn’t like the isolated experience of writing. (Put) five hermits in a room to socialize for fourteen hours?”

This more independent process at

SVU

initially can seem strange. Daniel Truly, who started on the show in time for season ten, had to readjust to the notion of flying solo.

SVU

initially can seem strange. Daniel Truly, who started on the show in time for season ten, had to readjust to the notion of flying solo.

“In some ways it’s slightly lonelier, because you don’t spend the first two hours every day sitting around telling what you did over the weekend,” Truly says. “You can still do all that, but you get a lot of time to do research, which you need for your episodes, and to work over the stories.”

Apart from his nostalgia for shooting the breeze with other writers, he appreciates

SVU

’s literary ambiance. “My experience has been you pitch an idea to Neal (Baer). He says, ‘I like it.’ You then pitch story beats to him as you go along and he says, ‘Go write an outline.’ You write an outline. He does notes (on it). You write a script. He gives you notes. . . . Neal and Amanda (Green) are always available, so if you need another writer to run stuff by, they’re all over the place.”

SVU

’s literary ambiance. “My experience has been you pitch an idea to Neal (Baer). He says, ‘I like it.’ You then pitch story beats to him as you go along and he says, ‘Go write an outline.’ You write an outline. He does notes (on it). You write a script. He gives you notes. . . . Neal and Amanda (Green) are always available, so if you need another writer to run stuff by, they’re all over the place.”

When former co-producer Paul Grellong started at

SVU

in 2005, he discovered that “they have a team of incredibly bright writers who are patient with new people.”

SVU

in 2005, he discovered that “they have a team of incredibly bright writers who are patient with new people.”

The more seasoned staff watches out for the new kids on the block. “Amanda Green did that for me,” Grellong says. “Neal and Amanda told me some of the areas they were interested in exploring. I wanted to write a script that was of the moment. That’s one thing the show is really good at: of the moment.”

Green relishes that mentoring role. “I supervise all the junior writers, so we have a process where I work with them to develop their ideas,” she says. “I’m sort of the intermediate step. A lot of what I do all day is working with younger writers, helping them find a way to tell the story they want to tell within the format of the show, within our conventions.”

Those conventions can be turned on their heads every now and then. What starts out as a sex-crime investigation may veer into very different territory, with an overarching issue—racism, homophobia, greed, government corruption, for instance—as the final denouement.

When working on her own projects, Green becomes something of a bookworm. “(If) I’m working on an episode about manic depression, I’m going to read memoirs and news articles about it. I have a full-time researcher whose job is to find me, say, the voices of manic depression. Whether it’s watching documentaries or reading books or whatever. Reading, reading, reading.”

Judith McCreary likes the Internet. “I’m always Googling,” she notes. “For example, I ran across a story about women who were raped more than once by the same guy and that made me wonder if his biological clock was ticking (“Confrontation” season eight) . . . I troll Lexis-Nexis (a subscription service that provides legal, governmental, and high-tech information sources). Or I look at

McKinney’s Consolidated Laws of New York Annotated

to understand the statutes. We don’t really do ripped-from-the headlines. That’s more the Mother Ship.”

McKinney’s Consolidated Laws of New York Annotated

to understand the statutes. We don’t really do ripped-from-the headlines. That’s more the Mother Ship.”

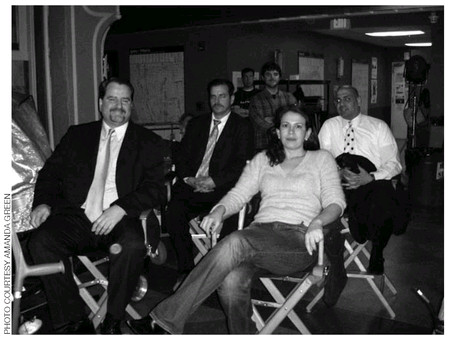

Executive producer Amanda Green on the set of season eight’s “Underbelly” with members of the NYPD.

Longtime

L&O

writer and Baer’s former

ER

colleague Robert Nathan (now with

Criminal Intent

), was on hand for the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons of

SVU

. He found the process there quite different from that of the Mother Ship: “One’s a sonnet, the other’s free verse.

Law & Order

is structurally more formal. After eighteen years, it holds to its roots: solve a crime, then see if the legal system can do its job.

SVU

is more fluid. It can be a quiet meditation one week and a suspense movie the next. You never quite know what you’ll get, which is one of the reasons the show remains so vibrant.”

L&O

writer and Baer’s former

ER

colleague Robert Nathan (now with

Criminal Intent

), was on hand for the fifth, sixth, and seventh seasons of

SVU

. He found the process there quite different from that of the Mother Ship: “One’s a sonnet, the other’s free verse.

Law & Order

is structurally more formal. After eighteen years, it holds to its roots: solve a crime, then see if the legal system can do its job.

SVU

is more fluid. It can be a quiet meditation one week and a suspense movie the next. You never quite know what you’ll get, which is one of the reasons the show remains so vibrant.”

Grellong, who came to

SVU

by way of theater, observes that

SVU

“leaves no stone unturned. Accuracy is really, really crucial. One of my favorite things about working there was that every week they turn out a forty-two-minute mystery set in a new world populated by unique characters.”

SVU

by way of theater, observes that

SVU

“leaves no stone unturned. Accuracy is really, really crucial. One of my favorite things about working there was that every week they turn out a forty-two-minute mystery set in a new world populated by unique characters.”

To make sure those mysteries are good, nobody at

SVU

is busier than showrunner Neal Baer. “I’m working on fourteen episodes right now, in various stages,” he explains, before enumerating several upcoming season ten titles. “In the last two days, I looked at ‘Lunacy,’ took notes with Arthur (Forney, an executive producer), worked on a re-edit of ‘Trials’ and a third rewrite of ‘Confession.’ Dan Truly will pitch me a script tomorrow. I’m reading Jonathan Greene’s episode about HIV, ‘Deniers.’ I’m communicating with (Casting Director) Jonathan Strauss about the parts we’ll offer for that episode.”

SVU

is busier than showrunner Neal Baer. “I’m working on fourteen episodes right now, in various stages,” he explains, before enumerating several upcoming season ten titles. “In the last two days, I looked at ‘Lunacy,’ took notes with Arthur (Forney, an executive producer), worked on a re-edit of ‘Trials’ and a third rewrite of ‘Confession.’ Dan Truly will pitch me a script tomorrow. I’m reading Jonathan Greene’s episode about HIV, ‘Deniers.’ I’m communicating with (Casting Director) Jonathan Strauss about the parts we’ll offer for that episode.”

In addition, Baer is “always asking the script supervisor what the timing is on a show. I’m looking at cuts. Maybe asking people to re-shoot things I don’t like. My researcher constantly emails me interesting articles.”

Plus, he’s involved with the publicity end of things otherwise expertly handled by Pam Golum and, until her retirement at the end of 2008 Audrey Davis of The Lippin Group, a bicoastal public relations firm that’s been with Wolf Films since 1994.

“I have my hand in everything,” surmises Baer. “I essentially rewrite every show but don’t always get credit because I feel that’s my responsibility as executive producer.”

In the communications business, the color red historically symbolizes editorial oversight, but not at

SVU

. “Every writer gets notes in purple ink,” he says of the script suggestions given to his team. “I have a big box of purple Pilot V-Ball pens. I got the idea from a neurosurgeon who wrote that way.”

SVU

. “Every writer gets notes in purple ink,” he says of the script suggestions given to his team. “I have a big box of purple Pilot V-Ball pens. I got the idea from a neurosurgeon who wrote that way.”

TV showrunning may not be brain surgery, but Neal Baer’s hands-on approach probably comes closer than most. He’s got a management style that seems to suit McCreary, at least. “Neal allows us a considerable amount of freedom to write what we feel most passionate about. I like to go to a place where the characters get irritated with each other. I like to explore aggressive tension between Fin and Stabler. . . . It gives us something to play with. Dick says verisimilitude is important. These things don’t resolve themselves. Let’s just let it stay there.”

The

SVU

endeavor was “a learning curve,” notes Michele Fazekas. “Having just one storyline is a huge challenge. Everything has to make sense and lead to the next thing. Doing a script is like boot camp. You have to be logical all the way through. Every scene had to be integral to the plot. That made me a better writer.”

SVU

endeavor was “a learning curve,” notes Michele Fazekas. “Having just one storyline is a huge challenge. Everything has to make sense and lead to the next thing. Doing a script is like boot camp. You have to be logical all the way through. Every scene had to be integral to the plot. That made me a better writer.”

Tara Butters, Fazekas’ writing partner, points out that the show has no specific formula, compared with the Mother Ship’s cops in the first half and courts in the second.

“Neal told us, ‘We don’t have to do it that way,” Fazekas says.

“Sometimes we’d start with meeting the killer in the teaser, or never meet him until the last scene,” Butters adds. “It’s a blessing and a curse as a writer. So much freedom can be daunting.”

Other books

For Desire Alone by Jess Michaels

Tales From A Broad by Fran Lebowitz

In Great Waters by Kit Whitfield

Ellis Peters - George Felse 03 - Flight Of A Witch by Ellis Peters

Little Knife by Leigh Bardugo

Drinking With Men : A Memoir (9781101603123) by Schaap, Rosie

Sounds of Murder by Patricia Rockwell

Longing by Mary Balogh

Luc: A Spy Thriller by Greg Coppin

Groomless - Part 2 by Sierra Rose