Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion (9 page)

Read Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion Online

Authors: Susan Green,Randee Dawn

BOOK: Law & Order: Special Victims Unit: The Unofficial Companion

6.4Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

For California-based producer Judith McCreary, the eye of the beholder is what counts and Manhattan exteriors just aren’t up her alley. “When I returned to New York for ‘Venom’ (season seven), it was my first time back there in, like, two years,” she recalls. “But it was really cold that winter and we were downtown, at 60 Centre Street, which is some sort of wind tunnel. I refused to go out and tried to change the script so we could shoot indoors. I didn’t get my way.”

Her New York nightmare was only getting started. “As I recall, the snow came; a horrible blizzard that dumped inches of snow and brought the city to a standstill,” McCreary says. “And imagine my concern when some pedestrians that weekend actually lost their lives by walking on grates in the sidewalk and getting electrocuted from exposed wires because the salt had eaten away their protective coating!”

Neither rain nor snow will keep Adlesic from her appointed rounds, which begin every six or seven days by “getting a new script and starting to break it down immediately,” she says of the “prep” phase. “I sit in on Uncle Ted’s Story Hour (a session with Kotcheff and other key staffers) and tell them my ideas.”

Adlesic and her team need to find roughly ten to twenty locations per episode. “We also have ‘bottle shows’ (shot primarily on the soundstage) that conserve money, because we have to pay for locations,” she points out. “But 30 to 40 percent of

SVU

is shot on ‘practicals’ (locations).”

SVU

is shot on ‘practicals’ (locations).”

On the set of season ten’s “Lunacy,” Battery Park City, New York

In terms of scouting, “I’m part of the assistant director’s team, with about five people,” Adlesic says. “We’re the cornerstone of the production.”

To pave the way, Adlesic asks writers to give her a heads-up “if they plan any challenging locations—like the subway—so I can hit the ground running. The Fire Department’s training academy does have a platform with modern trains.”

DeClerque works with Adlesic in this process. “The producer, episode director, production designer, location manager, first and second directors, we become joined at the hip,” he says. “We try to find hub locations—the Museum of Natural Science, for instance—and build a full day of shooting around that. Can’t find a doughnut shop the script calls for? Is it possible the guy could be in a bodega instead?”

And then there are those endless details, such as the distances an episode can travel without running up the cost. “I’m always mindful that the Screen Actors Guild rules specify only eight miles from the city for actors and the crew’s trade union (IATSE 52) says they can’t go beyond twenty-two miles. Otherwise, we pay penalties,” Adlesic says.

To secure a site, Adlesic has other hoops through which to jump. “I have a sense of what’s fair and within budget,” she contends. “Most people will negotiate. We draw up a legal document, get insurance, coordinate the crew. It’s remarkable how smooth that can be. But it’s always deliver, deliver, deliver. There’s not a lot of room for error. I have to be conscientious in every detail.”

She knows chaos is lurking around every corner. “It’s sort of like asking me to control the weather,” Adlesic says. “It’s the real world, with noises, airplanes, never-ending surprises. The New York City Mayor’s Office (of Film, Theatre & Broadcasting) has a list of certain hot-spots, neighborhoods in which we can’t film. We need to be very strategic: no hot-spot, no nearby construction going on, good parking. We try to make our impact as minimal as possible. We refer to this as ‘letting it live.’ That keeps the public happy.”

And when all else fails, “we can change at a moment’s notice,” she vows. “I have a sort of sixth sense about pulling out quickly if a negotiation seems headed to a dead end. But we can’t walk around with a crystal ball and imagine every scenario.”

CHAPTER EIGHT

WHAT WASN’T THERE BEFORE

E

very now and then Dean Taucher,

SVU

’s production designer since early in season one, has an interesting dilemma when called upon to make the Big Apple look worm-ridden. Or, as he puts it, “a taste of the 1970s when the city was collapsing.”

very now and then Dean Taucher,

SVU

’s production designer since early in season one, has an interesting dilemma when called upon to make the Big Apple look worm-ridden. Or, as he puts it, “a taste of the 1970s when the city was collapsing.”

Locations in today’s cleaner, more tourism-friendly metropolis may not yield the sort of mean streets a crime show requires. “We needed junk-filled empty lots,” Taucher says. “Can’t find them anymore. So we have to make it look like South Bronx of the 1980s. Sometimes we need grit and darkness and scariness to capture a mood. I come from New York. I’m familiar with urban decay, so I found that very appealing.”

His résumé indicates a propensity for crafting sets suitable for wrongdoers and the public servants who pursue them. While working as a visual consultant on

Miami Vice

(NBC, 1984-89), Taucher got to know that show’s then-head writer Dick Wolf. This relationship opened the door to various production designer jobs, on such programs as

H.E.L.P.

(ABC, 1990) and

New York Undercover

(Fox, 1994-98).

Miami Vice

(NBC, 1984-89), Taucher got to know that show’s then-head writer Dick Wolf. This relationship opened the door to various production designer jobs, on such programs as

H.E.L.P.

(ABC, 1990) and

New York Undercover

(Fox, 1994-98).

After a short stint with the non-Wolf series

Dellaventura

(CBS, 1997), several commercials, and a few TV movies, Taucher enabled mobsters on

The Sopranos

. Though he was only with the beloved HBO drama during its first season, his magic touch remained thereafter. “A lot of those permanent sets were my creations: the back-room of the strip club, the pork store, much of Tony’s house.”

Dellaventura

(CBS, 1997), several commercials, and a few TV movies, Taucher enabled mobsters on

The Sopranos

. Though he was only with the beloved HBO drama during its first season, his magic touch remained thereafter. “A lot of those permanent sets were my creations: the back-room of the strip club, the pork store, much of Tony’s house.”

Bada bing, bada boom. Taucher was tasked with giving

SVU

’s characters a range of equally true-to-life destinations. “It all has to feel real,” he says. “If not, that takes people out of the story.”

SVU

’s characters a range of equally true-to-life destinations. “It all has to feel real,” he says. “If not, that takes people out of the story.”

To achieve that goal, he collaborates with the art department, the set decorators, the props people, the carpenters, the grips, the scenic team—“probably twenty-five of them each day but that number can double or more,” Taucher points out.

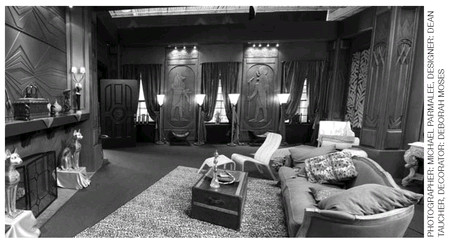

The hotel set from season ten’s “Lunacy,” pre-filming

The “Gots Money” set from season ten’s “Wildlife.”

The collective endeavor to lend authenticity to fiction doesn’t come cheaply. An extensive cave was essential for “Alternate,” a season nine episode with guest star and subsequent

SVU

Emmy-winner Cynthia Nixon. “But there are no caves in Manhattan,” Taucher says. “So we built one in our adjacent warehouse out of Styrofoam.”

SVU

Emmy-winner Cynthia Nixon. “But there are no caves in Manhattan,” Taucher says. “So we built one in our adjacent warehouse out of Styrofoam.”

Unit production manager Gail Barringer notes that this indoor cave cost $50,000, and “would have been maybe twice that if we’d used one somewhere outside.”

CHAPTER NINE

LEADING THE WAY

E

arly on, while

SVU’

s identity still seemed rather malleable, executive producer Ted Kotcheff was impressed by the innovative approach of a guest director: “In season one, Leslie Linka Glatter came (for ‘A Single Life’). She had been a dancer and that was the way she staged scenes. She made a big impact on how we do the show.”

arly on, while

SVU’

s identity still seemed rather malleable, executive producer Ted Kotcheff was impressed by the innovative approach of a guest director: “In season one, Leslie Linka Glatter came (for ‘A Single Life’). She had been a dancer and that was the way she staged scenes. She made a big impact on how we do the show.”

Her style involved graceful circling and swooping movements of the camera, as well as choreographing everyday “bits of business,” as actors call it, that frame the primary activity on screen. These ideas were enshrined by the time Peter Leto began taking the helm in season six. He had gone through quite a learning curve over the years, in fact, from key assistant director to first assistant director to production manager/co-producer.

“I was asked if I had any interest in directing,” Leto says. “But I was quite happy producing. I was helping novice directors who came in.”

Peter Leto

He wanted one more year as a producer before his directorial debut and apparent epiphany on “Goliath” (season six). “As clichéd as this sounds, a light went on in my head, in a dormant creative part of my brain,” Leto says. “I never knew I had such an ability to visualize what’s on the page. I got on-the-job training. My mentor is Ted Kotcheff—he’s the greatest film school I could ever have applied to.”

Showrunner Neal Baer also points out that “we have a movie director who makes actors very comfortable and it’s one reason the big stars like to come on. They feel, ‘Omigod, Ted Kotcheff!’”

Recently, Leto has been one of the people whose job mushroomed as

SVU

began to winnow down its freelance stable to provide more creative continuity. Although there are a few newbies each year, Leto remains among the few go-to guys. “When we started, I had maybe fifteen different directors a season,” Kotcheff explains. “Now, Peter does eight episodes, David Platt does eight, and we bring in only about six others.”

SVU

began to winnow down its freelance stable to provide more creative continuity. Although there are a few newbies each year, Leto remains among the few go-to guys. “When we started, I had maybe fifteen different directors a season,” Kotcheff explains. “Now, Peter does eight episodes, David Platt does eight, and we bring in only about six others.”

Baer is happy about the new arrangement: “It’s very smooth, with Peter Leto and David Platt directing most of the episodes. We found that bringing in itinerant directors made it difficult to always get the fluid style of camera movement I love.”

Platt went from boom operator to sound mixer on the original

Law & Order

, before he began periodically directing episodes during the Mother Ship’s sixth season. His contribution to

SVU

was kept at a minimum until season five.

Law & Order

, before he began periodically directing episodes during the Mother Ship’s sixth season. His contribution to

SVU

was kept at a minimum until season five.

Three years later, Platt began to seem indispensable. In season nine, he was promoted to the rank of producer and continued to fashion a variety of episodes. “I can do anything they throw at me,” he says. “There are certain writers I like to work with or maybe it has to do with a particular actor. Sometimes it’s just luck of the draw.”

Co-executive producer Arthur W. Forney, another in-demand director, says “Neal Baer and Ted Kotcheff decide who directs and in what order. They tell us a month before, while the script is still being written. In a TV series, you get what comes your way.”

Other books

Whipped by York, Sabrina

Maps by Nuruddin Farah

Perv (Filth #1) by Dakota Gray

A Virgin River Christmas by Robyn Carr

Diva Las Vegas by Eileen Davidson

Desperate Measures by Kate Wilhelm

Where Rainbows End by Cecelia Ahern

The Last Kind Words Saloon: A Novel by Larry McMurtry

The Jaguar by A.T. Grant

The Wolf in Her Heart by Sydney Falk