Life in a Medieval Village (26 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

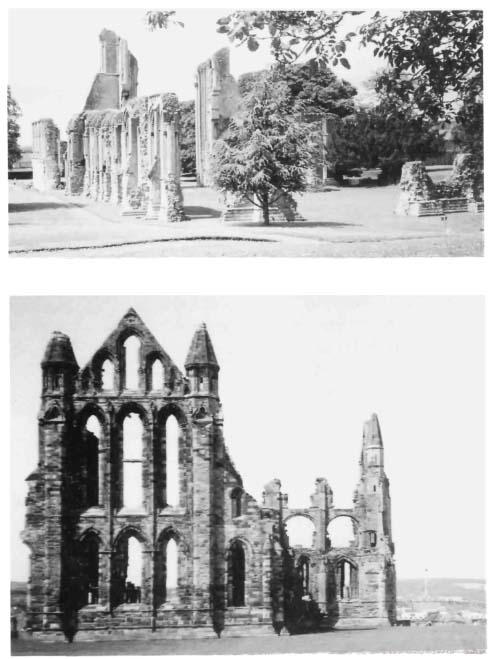

Relics of the Dissolution: ruins of Glastonbury Abbey (above) and Whitby Abbey. Of Ramsey Abbey, nothing medieval survives.

survived, some even gaining new population and character as numbers of craftsmen quit the cities, in part to escape guild regulation, and took their weaving, dyeing, tanning, and other skills to the now freer village environment. Some villages be

came primarily industrial. The village of Birmingham in the sixteenth century became a burgeoning town of 1,500, specializing in tanning and clothmaking.

34

At the same time cereal crop agriculture made belated progress. Yields improved, if slowly, in the seventeenth century, reaching a general average in England of seven to one.

35

Famine became largely a threat of the past. “Starvation…cannot be shown to have been an omnipresent menace to the poor in Stuart times,” says Peter Laslett.

36

In 1610 a Herefordshire husbandman named Rowland Vaughan solved the problem of meadow and hay shortage that had vexed medieval lord and villager by devising an irrigation technique.

37

This and other improvements in agricultural technology made possible the servicing of a rapidly expanding market for English produce in Britain, on the Continent, and in English colonies overseas. The market gave scope for the ambitious, the industrious, the competent, and the fortunate, creating new, deeper divisions of rich and poor among the villagers. Individual enterprise moved to the center of the economic stage, as those who could afford it took advantage of the land market to buy up and consolidate holdings, forming compact plots that could be enclosed by fences or hedges and set free from communal regulation. At the other end of the scale, the number of landless laborers multiplied. In some places the old open field arrangements, with their cooperative plowing, common grazing, and bylaws, hung on amid a changing world. In 1545 the hallmote of Newton Longville, Buckinghamshire, ordained “that no one shall pasture his beasts in the sown fields except on his own lands from the Feast of Pentecost next-to-come until the rye and wheat have been taken away under penalty of four pence…”

38

But the future of individualism was already assured. “The undermining of the common fields, the declining effectiveness of the village’s internal government, and the development of a distinct group of wealthy tenants [spelled the] triumph of individualism over the interests of the community,” in the words of Christopher Dyer.

39

Among the last guardians of the old communal tradition were

the English colonists who settled in New England, laid out their villages with churchyard and green (but no manor house), divided their fields into strips apportioned in accordance with wealth, plowed them cooperatively with large ox teams, and in their town meetings elected officials and enacted bylaws on cropping, pasturing, and fencing.

40

But in land-rich North America the open field village was out of place, and it soon became apparent that the American continent was destined for exploitation by the individual homestead farm. (It may be worth noting, however, that even technology-oriented American agriculture proved resistant to radical change; until the introduction of the tractor, one to two acres was considered an ample day’s work for two men and a plow team.)

The village of Elton survived famine, Black Death, the Dissolution, and the enclosure movement. It even gained an architectural ornament with the building of Elton Hall, an imposing structure surrounded by a moat, begun by Sir Richard Sapcote about 1470 and expanded in the following centuries along with many other new peasant houses and old manor houses that reflected the general prosperity. Richard Cromwell, a nephew by marriage of Henry VIII’s minister Thomas Cromwell, acquired Ramsey Abbey and became landlord of the dependent manors. Elton, however, went to another proprietor, through whom it gained a little guidebook distinction. The king bestowed it on his latest queen, Katherine Howard, as part of her jointure, the property settlement made on noble wives. On Katherine’s execution for adultery Henry took back the jointure and presently bestowed Elton in 1546 on his last wife, Katherine Parr, under whose regime Elton Hall was given extensive repairs. On her death in 1548 Elton reverted to the crown, now held by the infant Edward VI, from whom it passed to Queen Elizabeth and James I, who disposed of it to Sir James Fullerton and Francis Maxwell, from whom it passed through still other hands to Sir Thomas Cotton, who held what must have been one of the last

views of frankpledge in the manor court in 1633. Sir Thomas’s daughter Frances and her husband Sir Thomas Proby inherited Elton; from them it passed to a collateral branch, raised to the peerage as earls of Carysfort, and in 1909 went to a nephew who took the name of Proby, and whose descendants remain in residence in Elton Hall.

41

Enclosures, slow to penetrate Huntingdonshire, finally replaced the old arable strips and furlongs with rectangular hedged fields; one drives down a long straight road to arrive in a village whose irregular lanes and closes still carry a hint of the Middle Ages.

Though it had many ancestors in the form of hamlets, encampments, and other tiny, temporary, or semipermanent settlements, and though its modern descendants range from market towns to metropolitan suburbs, the open field village of the Middle Ages was a distinctive community, something new under the sun and not repeated since. Its intricate combination of social, economic, and legal arrangements, invented over a long period of time to meet a succession of pressing needs, imparted to its completed form an image, a personality, and a character. The traces of its open fields that aerial photographs reveal, with their faded parallel furrows clustered in plots oddly angled to each other, contain elements of both discipline and freedom.

Simultaneously haphazard and systematic, the medieval village is unthinkable without its lord. So much of its endless round of toil went to cultivate his crops, while its rents, court fines, and all the other charges with the curious archaic names went to supply his personal wants and the needs of his monastic or baronial household. Yet at the same time the village enjoyed a high degree of autonomy, regulating its own cultivation, settling its own quarrels, and living its life with little interference.

The legal division of the villagers into “free” and “unfree” had genuine meaning, but went much less deep than the words imply. The unfree villeins had to work for the lord and pay many

fees that the free tenants escaped, yet the division into prosperous and poor was more meaningful. Looking at the men of the Middle Ages, Marc Bloch asked, “In social life, is there any more elusive notion than the free will of a small man?”

42

Village life for men and women alike was busy, strenuous, unrelenting, much of it lived outdoors, with an element of danger that especially threatened children. Diet was poor, dress simple, housing primitive, sanitary arrangements derisory. Yet there were love, sex, courtship, and marriage, holidays, games and sports, and plenty of ale. Neighbors quarreled and fought, sued and countersued, suspected and slandered, but also knew each other thoroughly and depended on each other, to help with the plowing and harvesting, to act as pledges, to bear witness, to respond when danger threatened.

The most arresting characteristic of the medieval open field village is certainly its system of cooperation: cultivation in concert of individually held land, and pasturing in common of individually owned animals. It was a system that suited an age of low productivity and scarcity of markets, and one that hardly fostered the spirit of innovation. The lords were content to leave things as they were, the villeins had little power to change them. When change came, it came largely from outside, from the pressure of the market and the enterprise of new landlords. Yet change builds on an existing structure. The open field village helped create the populous—and in comparison with the past, prosperous—Europe of the high Middle Ages, the Europe from which so much of the modern world emerged.

In the shift toward that world, many villagers lost their homes, many of their villages disappeared. Argument, protest, and violence accompanied change, which only historical perspective makes clearly inevitable.

Was something larger lost? A sense of community, of closeness, of mutual solidarity? Perhaps it was, but the clearest message about the people of Elton and other villages of the late thirteenth century that their records give us seems to be that they were people much like ourselves. Not brutes or dolts, but men and women, living out their lives in a more difficult world,

one underequipped with technology, devoid of science, nearly devoid of medicine, and saddled with an exploitative social system. Sometimes they protested, sometimes they even rose in rebellion, mostly they adapted to circumstance. In making their system work, they helped lay the foundation of the future.

PROLOGUE: ELTON

1.

Chronicon abbatiae Rameseiensis,

ed. by W. Duncan Macray, London, 1886, p. 135.

2.

Maurice Beresford and John G. Hurst, eds.,

Deserted Medieval Villages,

London, 1971; Maurice Beresford,

The

Lost

Villages of the Middle Ages,

London, 1954; John G. Hurst, “The Changing Medieval Village,” in J. A. Raftis, ed.,

Pathways to Medieval Peasants,

Toronto, 1981; Trevor Rowley and John Wood,

Deserted Villages,

Aylesbury, England, 1982.

1.

THE VILLAGE EMERGES

1.

Edward Miller and John Hatcher,

Medieval England: Rural Society and Economic Change, 1086-1348,

London, 1978, pp. 85-87.

2.

Rowley and Wood,

Deserted Villages,

pp. 6-8.

3.

Jean Chapelot and Robert Fossier,

The Village and House in the Middle Ages,

trans. by Henry Cleere, Berkeley, 1985, p. 327.

4.

P. J. Fowler, “Later Prehistory,” in H. P. R. Finberg, gen. ed.,

The

Agrarian

History of England and Wales,

vol. 1, pt. 1,

Prehistory,

ed. by Stuart Piggott, Cambridge, 1981, pp. 157-158.

5.

Butser Ancient Farm Project Publications:

The Celtic Experience; Celtic Fields; Evolution of Wheat; Bees and Honey;

Quern Stones; Hoes,

Ards, and Yokes; Natural Dyes.

6.

Tacitus,

De Vita Iulii Agricola and De Germania,

ed. by Alfred Gudeman, Boston, 1928, pp. 36-37, 40-41.

7.

Chapelot and Fossier, Village

and House,

pp. 27-30.

8.

S. Applebaum, “Roman Britain,” in H. P. R. Finberg, ed.,

The Agrarian History of England and Wales,

vol. 1, pt. 2, A.D.

43-1042,

Cambridge, 1972, p. 117.

9.

Ibid., pp. 73-82.

10.

Ibid., pp. 186, 208.

11.

Chapelot and Fossier,

Village and House,

pp. 61, 100-103.

12.

Ibid., p. 26.

13.

Ibid., p. 15.

14.

Ibid., pp. 144-150.

15.

Joan Thirsk, “The Common Fields” and “The Origin of the Common Fields,” and J. Z. Titow, “Medieval England and the Open-Field System,” in Peasants,

Knights, and Heretics: Studies in Medieval English Social History,

ed. by R. H. Hilton, Cambridge, 1981, pp. 10-56; Bruce Campbell, “Commonfield Origins—the Regional Dimension,” in Trevor Rowley, ed., Origins

of Open-Field Agriculture,

London, 1981, p. 127; Trevor Rowley, “Medieval Field Systems,” in Leonard Cantor, ed.,

The English Medieval Landscape,

Philadelphia, 1982; H. L. Gray,

English Field Systems,

Cambridge, Mass., 1915; C. S. and C. S. Orwin,

The Open Fields,

Oxford, 1954.

16.

Joseph and Frances Gies,

Life

in

a Medieval Castle,

New York, 1974, p. 148.

17.

George C. Homans,

English Villagers

in

the Thirteenth Century,

New York, 1975, pp. 12-28.

18.

Grenville Astill and Annie Grant, eds.,

The Countryside of Medieval England,

Oxford, 1988, pp. 88, 94.

19.

Georges Duby, Rural Economy and Country

Life in the Medieval West,

Columbia, S.C., 1968, pp. 109-111.

20.

Joan Thirsk, “Farming Techniques,” in Agrarian History

of England and Wales,

vol. 4, 1500-1640, ed. by Joan Thirsk, Cambridge, 1967, p. 164.

21.

R. H. Hilton,

The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism,

London, 1984, pp. 15-16.

22.

W. G. Hoskins,

The Midland Peasant: The Economic and Social History of a Leicestershire

Village, London, 1957, p. 79; Homans,

English Villagers,

p. 368.

2.

THE ENGLISH VILLAGE: ELTON

1.

For Huntingdonshire: Peter Bigmore,

The Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire Landscape,

London, 1979. For England in general: H. C. Darby, A

New Historical Geography of England Before 1600,

Cambridge, 1976; Cantor, ed.,

The English Medieval Landscape;

W. G. Hoskins,

The Making of the English Landscape,

London, 1955.