Listening In (26 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

MEETING WITH DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., SEPTEMBER 19, 1963

The euphoria of the March on Washington did not last long, as conditions continued to deteriorate in Birmingham. On Sunday, September 15, the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan. The bomb killed four girls and wounded twenty-two others. Anger seethed through many of the leaders of the movement as they came to the Oval Office to vent their frustration and demand justice.

AMBASSADOR ADLAI STEVENSON, THE U.S. DELEGATE TO THE UNITED NATIONS, SHAKES HANDS WITH MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., PRESIDENT OF THE SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE, AT THE WHITE HOUSE ON DECEMBER 17, 1962. THE MEETING OCCURRED AS PRESIDENT KENNEDY MET WITH MEMBERS OF THE AMERICAN NEGRO LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE ON AFRICA

MLK:

We come today representing Birmingham in general, and more specifically some two hundred business and professional, religious, labor leaders who assembled the day after the bombing to discuss the implications and to discuss the seriousness of the whole crisis that we face there in Birmingham. And we come to you today because we feel that the Birmingham situation is so serious that it threatens not only the life and stability of Birmingham and Alabama, but of our whole nation. The image of our nation is involved, and the destiny of our nation is involved. We feel that Birmingham has reached a state of civil disorder.

Now, there are many things that you could say that would justify our coming to this conclusion. I’m sure you are aware of the fact that more bombings of churches and homes have taken place in Birmingham than any city in the United States, and not a one of these bombings over the last fifteen to twenty years has been solved. In fact, some twenty-eight have taken place in the last eight to ten years and all of these bombings remain unsolved. There is still a great problem of police brutality, and all of this came out in tragic dimensions Sunday when the bombing took place and four young girls were killed instantly, and then later in the day, two more. I think both were boys, the other two who were killed.

Now, the real problem that we face is this. The Negro community is about to reach a breaking point. There is a great deal of frustration and despair and confusion in the Negro community, and there is a feeling of being alone and not being protected. If you walk the street, you aren’t safe. If you stay at home, you are not safe, there is a danger of a bomb. If you’re in church now, it isn’t safe. So that the Negro feels that everywhere he goes, if he remains stationary, he’s in danger of some physical violence.

Now, this presents a real problem for those of us who find ourselves in leadership positions, because we are preaching at every moment the philosophy and the method of nonviolence. And I think that I can say without fear of successful contradiction, that we have been consistent in standing up for nonviolence at every point, and even with Sunday’s and Monday’s developments, we continue to be firm on this point. But more and more, we are facing a problem of our people saying, “What’s the use?” and we find it a little more difficult to get over nonviolence [to them].

And I am convinced that if something is not done to give the Negro a new sense of hope and a sense of protection, there is a danger that we will face, and that will lead to the worst race rioting we’ve ever seen in this country. I think it’s just at that point. I don’t think it will happen if we can do something to save the situation, but I do think—and I voiced the sentiment in the evening as well with those that we met with the other day—that something dramatic must be done at this time to give the Negro in Birmingham and Alabama a new sense of hope and a good sense of protection.

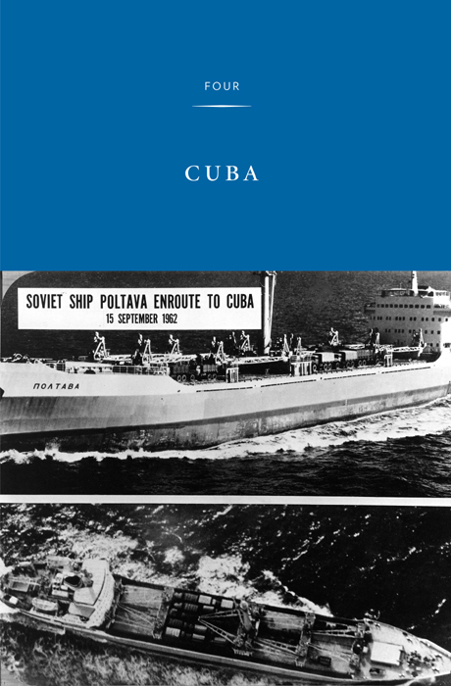

SURVEILLANCE PHOTOGRAPHS OF SOVIET SHIP

POLTAVA

EN ROUTE TO CUBA, SEPTEMBER 15, 1962

T

he Cuban Missile Crisis was, in the words of British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, a “strange and still scarcely explicable affair.” Macmillan added that it represented the greatest period of strain in his many decades of public service, including World War II. It is generally agreed by historians that the crisis, which extended from October 16 to October 28, 1962, represented the high water mark of a Cold War that lasted nearly half a century between the United States and the Soviet Union. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was more specific and said that these two weeks saw “what many of us felt then, and what since has been generally agreed, was the greatest danger of a catastrophic war since the advent of the nuclear age.” In Robert Kennedy’s opinion, it threatened nothing less than “the end of mankind.” Scientists had previously estimated that an initial exchange of nuclear missiles would rain death upon seventy million people in both the Soviet Union and the United States. Fortunately, that theory remained a hypothesis only.

It began quietly enough, with overhead surveillance photographs that indicated new construction in Cuba. As the evidence was studied, and gradually ascertained to prove new missile installations built by Soviet technicians, it was clear that all of the underlying assumptions of the Cold War had changed. Robert Kennedy records that his brother called him on the morning of October 16, simply telling him that there was “great trouble.”

That trouble was political in many ways. President Kennedy had to both conciliate and stand up to the Soviet Union, in the right measure; he had to win over the court of world opinion; and he had to guide forward a measured American response from a government that did not entirely speak with one voice. The Joint Chiefs of Staff demanded immediate retaliation of a kind that almost certainly would have led to a thermonuclear apocalypse. As they encountered resistance from the President, one of their more outspoken leaders, Air Force General Curtis LeMay, accused Kennedy of “appeasement,” a word with a rich legacy, tracing back to Neville Chamberlain’s futile accommodation of Adolf Hitler in 1938. Few historians had studied that episode more closely than Kennedy himself.

But Kennedy had on his side the fact that the Soviet Union had baldly lied about its intentions. It also became clear, not long into the crisis, that most of the world stood with him. A complex diplomacy ensued, involving official communiqués, back-door messages, speeches to the nation, confrontations in the United Nations, and a crucial decision to accept certain offers and to reject others as if they never existed. As the tapes reveal, the President was also supported by a superb leadership team that functioned effectively as a unit, going with little sleep and working incessantly to improve his options from the unthinkable to the unpalatable, and ultimately to the acceptable. The resulting decision not to go to war was greeted with euphoria around the world and brought many dividends, including a calming of international tensions, and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

The Cuban Missile Crisis remains noteworthy for another reason—it shows off the taping system to its finest advantage. We will never know all of the reasons that President Kennedy installed his tapes, but if he was worried about the poor advice he was receiving on military matters, the tapes bear that theory out, and bear witness to this day. They, too, performed well—they rolled through the crisis, and the result is a historic record of enormous importance for any student of the presidency and how it functions in a time of near-cataclysm.

MEETING WITH MILITARY ADVISORS, OCTOBER 16, 1962

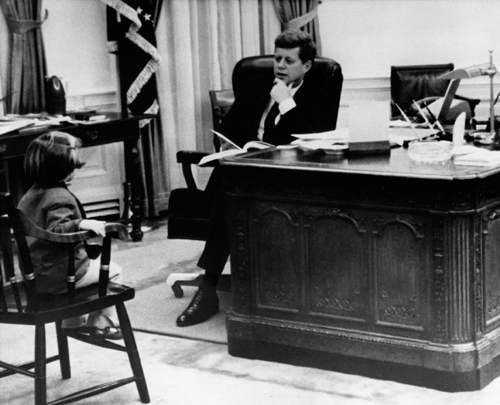

This meeting, the first in response to the crisis, begins with a brief conversation between a four-year-old Caroline Kennedy and her father, as the meeting was getting under way.