Mac Hacks (2 page)

. Before You Hack

Hacking is fun and productive, but it can also introduce an element of

danger (perhaps that’s part of the fun). You want to minimize that danger,

and the best way to minimize the bad stuff that can happen is to back up

your data and know what to do when something goes wrong. This is why this

chapter is here. You’ll discover some basic hacking techniques but, before

you try them, you’ll learn how to protect your precious data. If something

does go wrong, you’ll have the tools to fix the problem very quickly. The

interesting world of hacking awaits!

. Create a Great Backup

Even if you never plan to perform a single hack in this book, you’ll

still want a reliable backup. This hack explains different methods you can

use to back up your Mac so you can be confident that you’ll be able to

recover quickly when things go wrong.

If

you’re ever asked what the most important part of a computer

is (and that’s a question companies sometimes ask employment seekers), you

could do much worse than saying, “A good backup.” Why not, say, the CPU or

graphics card instead? Because a good backup is where all your work, toil,

pictures, movies, and other accumulated data is preserved for that

inevitable moment when everything stops working. With a good backup, you

don’t start over, you simply restore.

Without

a good

backup, well, good luck getting that loved one to put on a prom outfit 5

years later.

The point is that some things can’t be re-created (and even the ones

that

can

be re-created might take an obscene amount

of time and effort and, likely, still not be as good as the original). So

your goal should be to both minimize downtime and minimize lost data—and a

good backup helps you achieve both these goals.

The phrase “a good backup” gets tossed around a lot, but it’s

rarely ever defined. What is a good backup? That depends on what data

you don’t care about and what data you couldn’t stand to lose. For our

purposes, “a good backup” is one that saves your precious data and gives

you peace of mind. To find the backup method that’s right for you, we’ll

look at several different options for backing up your computer.

While

backing up is a great idea if you store any critical or

nonreplicable information on your computer, there’s a chance that the

amount of data that’s stored exclusively on your computer and nowhere

else is very small.

For example, if you’re a big-time photo sharer, all your pics

might be on Flickr. Or you might be a huge fan of iTunes Match, store

all your documents in iCloud, and have purchased all your apps via the

App Store. If this more or less describes you, you might not even want

to hassle with a backup because you’re generally using backups all the

time. To put a finer point on it, if your Mac were to get wiped out,

all your data would still exist in the cloud somewhere. Conversely, if

the cloud were to go dark, everything’s on your Mac. Your penchant for

accessing your data everywhere has saved you the hassle of backing

up!

The

most user-friendly way to back up your Mac is Time

Machine (

Figure 1-1

), which

is built into OS X and is incredibly easy to use. The idea behind Time

Machine is simple: you hook a drive up to your Mac and Time Machine

copies the drive. Once the drive is copied, Time Machine incrementally

copies any changes you make (file by file). If you lose a file or

something goes wrong, you can step backwards in time to the good old

days when everything was how you wanted it or just retrieve the file

that’s missing.

Time Machine backups are good enough for most people, but if

you’re going to be hacking around on your Mac and trying stuff you

wouldn’t normally try, you’ll likely want something a little beefier.

Creating a backup you can boot from (which you can’t do with Time

Machine) is a nice place to start. The next section explains how to

create one.

right side of the screen to scroll back in time and retrieve the data

you’re missing, or restore your Mac to how it was on a specific

date.

Unless you tell it otherwise, Time Machine backs your Mac up

every hour. You might find that to be too often or—if you’re working

on important stuff—not often enough. Fortunately, with a text editor

and a little determination, you can change that interval. Navigate

to:

your hard/System/Library/LaunchDaemons/com.apple.backupd-auto.plist

drive

Copy that file, and then open it with a text editor. The file

isn’t long so you won’t have any problem finding the line that

reads:

3600 is the number of seconds betwixt backups, so increase or

decrease that number until the interval seems ideal to you. Replace

the original file with the edited version you just created, and Time

Machine will back up according to your

schedule!

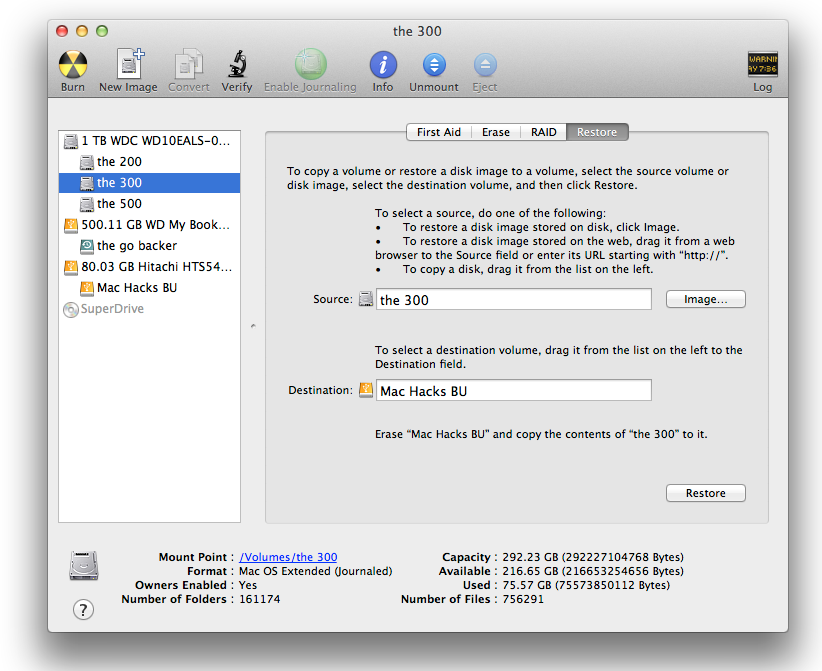

Your

Mac comes with a nice utility for duplicating drives.

It’s called Disk Utility and you’ll find it, as you’d expect, in the

Utilities folder (

Applications/Utilities/Disk

Utility

). That takes care of the software you’ll need, but

you’ll also need some media to store your backup on. In a perfect world,

you’d have a massive amount of super speedy storage. But since this

media is for backup purposes, cost considerations can be more critical

than high speed, so whatever you’re comfortable with will do. Just make

sure the drive/flash stick/ssd/partition you use is the same size or

larger than the disk you want to backup.

Attach your backup media to your Mac in the manner required by the

media. (I usually just jam the connector blindly into the back of my

machine until it fits, but you might want to use more care.) Next launch

Disk Utility. Once Disk Utility is up and running, you can get to the

business of duplicating your drive. Click the Restore tab and then drag

the disk you want to copy from the sidebar into the Source field. You

can guess what’s next: drag the disk that you want the back up to into

the Destination field (

Figure 1-2

).

to the partition Mac Hacks BU. OS X treats separate partitions as

different disks even though they can be on the same physical drive.

This illustration shows three physical drives and five

partitions.

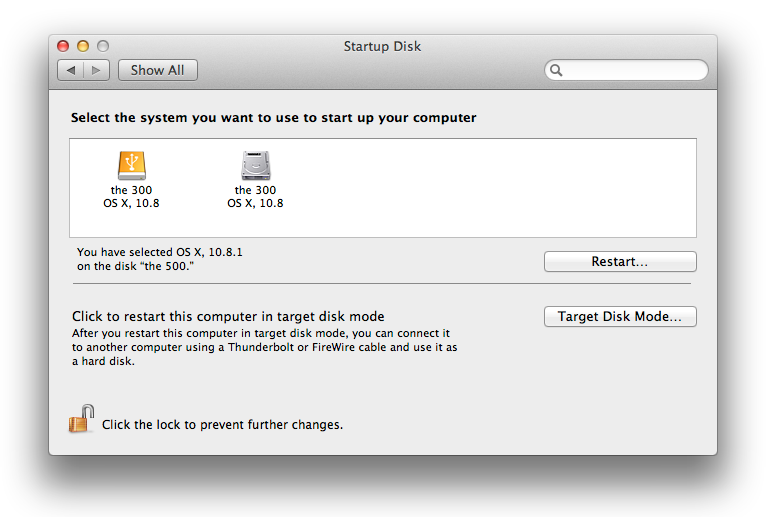

Click Restore and OS X displays a message asking if you’re

sure

you want to replace the contents of the

targeted drive. You’re careful and you’ve thought this out, so click

Erase. Once you do that, you’ll be asked for your password.

Type

in your password and Disk Utility will go about the

business of copying the data to the destination drive. Unlike Time

Machine, which copies drives file by file, Disk Utility works by copying

drives block by block, which yields an exact copy of the drive and keeps

it bootable. (If you use a copy method that copies file by file, the

result won’t be bootable unless you take some extra steps.) When the

process is finished you’ll have a new drive with all your old data that

you can use to boot your Mac if things go horribly awry. But before you

start sloshing cola on your old drive, take a quick trip to System

Preferences and choose Startup Disk. If the backup process went

smoothly, you’ll see an option to use the drive you just cloned as a

startup disk. As shown in

Figure 1-3

, the name of your

newest drive has been changed to match the name of the drive you just

cloned.

backup disk is bootable. Note that there are now two drives named “the

300.” You can tell them apart by their different icons: the one on the

left (the backup) is a USB drive, and the one on the right (the

original) is a hard drive.

. Create a Bootable Flash Drive

Your

installation of OS X has recovery tools built into it. But

because those tools are stored on your hard drive, they won’t do you any

good if the thing wreaking havoc with your Mac

is

the

drive. This hack explains how to make a cheap startup disk using a USB

stick and a free Apple-supplied

program.

In the olden times, back when you had to install new versions of OS

X from a DVD, you always had an emergency startup disk. Snow Leopard

acting wonky? Cram that DVD into your iMac’s superdrive, press Option-O

when it starts, and boot from the install disk. It was a slow process but

at least it got your Mac going again.

OS X Lion

and Mountain Lion are different. Since they don’t have

physical install disks, the emergency boot option is installed on your

drive when you install Lion or Mountain Lion. This is called the recovery

partition and it’s a tiny slice of the media you use to boot from. This

slice holds a bunch of nifty tools for you to use in an emergency (for a

more thorough discussion of the emergency boot partition, see

[Hack #7]

). The unfortunate thing is that none

of those will do you any good if something is wrong with the drive.

What you really need is a way to create a bootable disk. Happily,

Apple offers a program to do exactly that, it just isn’t all that well

known and—truth be told—once you’re interested enough to learn about it on

your own, it might be too late to solve your

problem.

How

do you get your own slice of USB-startup-disk heaven?

Point

your Mac to

the support page for OS X

Recovery

and click the download link on the upper right side of

the page. It’s a small file (1.1 MB) so the download will be quick. (If

the link listed here doesn’t work for you, a web search forOS X Recovery Disk Assistantwill find the program).

Recovery Disk Assistant arrives as a

.dmg

file.

As you’d expect, double-clicking this file will expand and give you access

to the program. You can move it to your Applications folder, but you’ll

likely want different versions of a recovery disk for all your different

Macs, so save the app to each of your Macs.

Macs

If you have multiple Macs, your inclination might be to make one

Recovery USB stick, place it behind glass with a hammer attached by a

chain, and use it in the event of an emergency with any of your Macs.

That plan

seems

solid, but it might not

work.

The general rule is that if you’ve upgraded your Mac to Lion or

Mountain, and created the recovery disk on that machine, it will work on

any other Mac you’ve upgraded in the same manner. So if you’ve got an

iMac and a MacBook Pro that both shipped with Snow Leopard and you’ve

upgraded both of them to Mountain Lion, the recovery disk you created on

one machine will work on both of them. But if the iMac has been upgraded

to Mountain Lion and the MacBook is still using Lion, the recovery disk

won’t

work on both computers. Things get weirder if

you have a Mac that came with Lion or Mountain Lion preinstalled. For

such machines, only recovery disks made on the same machine you’re using

them for will work. Want to use a USB recovery stick with your 2012

Retina MacBook Pro? You’d better make sure you made it on that

machine.

The easiest solution? Just make one recovery disk for each

computer, on each computer. Mark which one is which and hope you never

need them.

Grab a blank USB drive that’s at least 650 MB in size that has no

important data on it (Recovery Disk Assistant erases all the data as it

creates the disk). Now is a great time to rename the USB disk to something

easily recognizable. (To rename the disk, plug it into your Mac and, when

the disk’s icon appears onscreen, click the icon and then click its name;

then type the new name. This isn’t a long-term commitment: once the

process is done, you won’t see the disk at all, so don’t fret over the

name.)

So your drive is plugged in, devoid of necessary data, and named

something you can spot easily. Great—the hard work is done. Launch

Recovery Disk Assistant (

Figure 1-4

) and let your Mac do

the hard work! You’ll be asked for your password and then Recovery Disk

Assistant will take a few minutes to actually write the disk.

choice carefully as the selected disk will be erased.

Once everything is in place, Recovery Disk Assistant will tell you

that the process is finished and you’ll have a disk you can use to start

your Mac when things go wrong. Since the disk is a copy (more or less) of

the recovery partition built into your hard drive, it’ll give you access

to all the same tools you’d have if you booted from the recovery disk

(Disk Utility, Terminal, etc.).

There’s a downside to this method, however: from now on, when you

insert the disk into your Mac’s USB slot, nothing shows up onscreen.

That’s because that disk is dedicated

only

to booting

your Mac and helping you recover—you can’t use it for anything else.

(There is a workaround that will make your Mac display the disk: shut

down, plug in the disk, and then hold down the Option key while you start

up.) For that reason, you probably want to boldly label the disk with the

name of the machine you created it on.

Honestly, the whole process is kind of cumbersome—creating specific

disks for specific Macs (but only sometimes)—but in an emergency the disks

can be real lifesavers.