Meatonomics (28 page)

Authors: David Robinson Simon

Taxing authorities around the world have successfully used Pigovian taxes in a variety of ways. Most notable, perhaps, are programs that use tobacco taxes to reduce cigarette smoking and increase tax revenues. In the United States, we tax cigarettes at the federal, state, and—in some cases—city level. This combination is highest in New York City, where a pack of cigarettes carries taxes of $5.85 and sells for $11 or more. Amazingly, this hefty tax still falls far short of the total externalized costs of cigarettes. Recovering that entire figure

would require imposing taxes of $10.47 per pack (according to the latest estimate by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), or nearly three times the average pre-tax price of a pack of cigarettes.

8

Nevertheless, cigarette taxes do work. Studies show that depending on the affected consumer group's age, income level, and extent of addiction, a 10 percent cigarette tax lowers smoking by 4 to 14 percent.

9

Moreover, cigarette taxes lead to huge revenue boosts. In Texas, for example, a 2007 cigarette tax hike of $1 per pack increased state tax revenues in the first year by more than $1 billion—while lowering cigarette sales in the state by 21 percent.

10

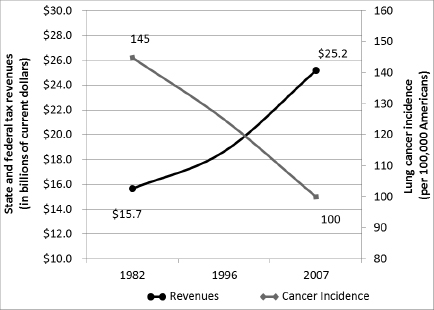

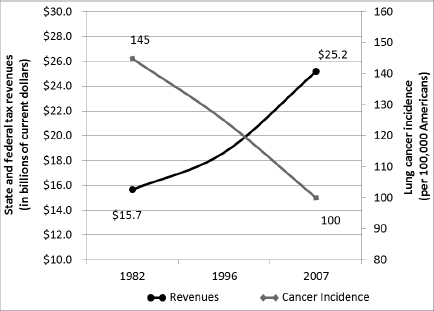

Consider the huge gains that cigarette taxes have yielded for both personal health and government revenue since the early eighties, when state and federal governments began aggressively increasing these levies. From 1982 to 2007, inflation-adjusted prices of cigarettes nearly tripled as a result of increases in state and federal tobacco taxes.

11

During the same period, moving virtually in lockstep with the tax increases, US per capita cigarette consumption dropped more than 50 percent and the incidence of lung cancer among Americans fell 30 percent.

12

The tax increases paid a double dividend as well: despite the significant decline in consumption, combined state and federal tobacco tax revenues grew during the period from $15.7 billion to $25.2 billion (in inflation-adjusted dollars).

13

Table 10.1

shows the direct, negative correlation between cigarette prices and consumption, and

table 10.2

shows the double dividend: an increase in tax revenues and simultaneous decrease in lung cancer incidence.

Taxes aren't the sole reason for Americans' declining consumption of cigarettes. For decades, government agencies and nonprofits have engaged in regulatory and public relations campaigns against tobacco use. These have yielded stricter labeling laws, restrictions on cigarette advertising, and billboard, radio, and TV ads that warn of smoking's dangers. But data from other countries, where cigarette taxes have been overwhelmingly successful even in the absence of American-style regulatory and public relations efforts, show that taxes are the most important part of any antismoking campaign. In Mexico, new tobacco taxes imposed between 1981 and 2007 led to cigarette prices

tripling and consumption dropping by half.

14

In France, a 27 percent tax increase between 2003 and 2004 caused consumption to fall 7 percent.

15

And in Japan, a 2010 tax increase led to the steepest year-over-year consumption drop (2.2 percent) ever seen in that country.

16

These results from around the world show that even without help from public relations, taxes unquestionably work to reduce consumption.

TABLE 10.1

US Cigarette Prices and Consumption, 1982–2007

TABLE 10.2

US Cigarette Tax Revenues and Lung Cancer Incidence, 1982–2007

Just as it has for cigarettes, a tax on animal foods would pay a double dividend by simultaneously boosting revenues and lowering consumption (and related social problems). Recall that the weighted average elasticity rate (that number that ties demand to price) for all animal foods is about 0.65.

17

A 3 percent tax on animal foods, for example, would reduce consumption by about 2 percent and generate about $7.4 billion in revenue.

18

Of course, because we've seen that animal foods generate external costs worth nearly double their retail prices, a 3 percent tax in this category is unlikely to do much. The average cigarette tax in the United States is a hefty 72 percent.

19

Accordingly, in light of the slightly smaller ratio of external costs generated by animal foods, I propose a

50 percent federal excise tax

on all domestic retail sales of meat, fish, eggs, and dairy.

20

For simplicity, I refer to this across-the-board tax on animal foods as the Meat Tax.

The way the tax would work is simple. Every food item intended for human consumption that contains any animal product as an ingredient or component would be subject to a 50 percent tax imposed at the retail point of sale. For example, including the tax, a $10 store-bought steak would cost $15, a $4 Big Mac would cost $6, and a $2 Baskin-Robbins ice cream cone would cost $3. Goods containing only negligible amounts of animal foods, like cookies containing egg, or bread containing whey (a milk by-product), are nonetheless taxed at the usual Meat Tax rate. Why? Two reasons. First, trying to set thresholds for the tax's applicability would be both costly to administer and impractical to enforce. Second, any ingredient that is negligible can, by definition, easily be replaced or eliminated, which means producers who want to avoid the tax can easily change their foods' composition. The fact that, for example, many brands of bread and cookies contain no animal products shows how easy it is to make such items without animal foods. In fact, one of the tax's benefits is that it would encourage producers to reformulate the composition of such hybrid goods. As the proverb goes, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” Plus, beyond healthier

new edible combinations, the revised goods would impose lower external costs on society.

“I shall never use profanity,” said Mark Twain, “except in discussing house rent and taxes.” Like Twain, many will find it hard to swallow a new tax, especially one applied to common dietary staples. That's why there's another feature meant to soften the blow.

In conjunction with the Meat Tax, each American taxpaying individual or family would get an annual tax credit averaging about $560 (the precise amounts range from $410 for single filers to $750 for married joint filers).

21

This would cost the US Treasury $78 billion, admittedly a nontrivial figure.

22

But the revenue and cost savings resulting from the Meat Tax will not only offset this cost but will also provide a comfortable cushion above it. Thus, after accounting for the reduced demand that it causes, the tax and other changes would yield an annual cash surplus of more than $32 billion.

23

Why a tax credit? For one thing, the amount of the credit will offset the extra tax burden on each taxpaying individual or family (after adjusting for lower consumption), so that Americans' ability to eat will not be diminished. Further, the spending-related stimulus will help offset the lower spending caused by other parts of the plan. Finally, it's the quid pro quo, the benefit to individuals, that will motivate voters and lawmakers to support the overall plan.

Wouldn't a tax credit be useless to people who pay no income taxes—a group which recent estimates put at nearly half the US population? Actually, even those who pay no taxes can turn a tax credit into cash by simply filing a tax return. That's why some filers get tax refunds based on items like the Child Tax Credit and the Lifetime Learning Tax Credit even though they have no taxable income and pay no taxes. The fact that those with lower incomes are disproportionately more likely to pay no taxes

does not

mean the poor will be less able than others to take advantage of the proposed tax credit. To the contrary, there's evidence the poor are generally well-informed about tax credits and other benefits to which they may be entitled.

24

The USDA, as we've seen, is riddled with built-in conflicts that make it almost impossible to discern its purpose or message. Many critics, including lawmakers like former US Senator Peter Fitzgerald (R-IL), have proposed reorganizing the agency to eliminate some of these inherent contradictions. The USDA should keep its original, Lincoln-era purpose of helping farmers and other rural Americans. But the duties of regulating animal food labels and inspecting meat and dairy plants, which frequently require the agency to act in a way opposed to its clients' interests, must be revamped. The FDA already performs these functions for most other foods and is the logical choice to take over these tasks.

The USDA should also completely exit the business of promoting animal foods and leave that to the trade organizations. There is simply no reason for the US government to encourage the heaviest people on Earth to eat more fat-rich food. Checkoff programs for animal foods should be discontinued so costs are no longer routinely passed on to consumers for messages that many consider insidious and inappropriate. Some people argue that food is a necessity and this warrants government reminders to eat. Clothing is also a necessity, but Americans manage to dress ourselves without bureaucrats reminding us to buy and wear garments. We don't have—or need—a taxpayer-funded Department of Clothing to help Gap and Benetton sell their products. Because we've seen checkoffs drive about $4.6 billion in annual sales of animal foods, or 1.8 percent of the industry's total annual sales of $251 billion, we can expect that eliminating these programs would reduce consumption by about 1.8 percent.

25

Finally, both the USDA's food stamp program, and the agency's authority to make nutrition recommendations, should be turned over to the Department of Health and Human Services. For decades, animal food producers have sought—usually with great success—to influence these programs in order to sell more goods. Removing the functions of nutrition assistance and guidance from the agency tasked with helping meat and dairy farmers sell more product would end the worst conflicts of interest that plague the USDA.

We're not done with the USDA. With annual spending on farm and nutrition programs of $209 billion, mostly funded by taxpayers, the agency is the primary vehicle through which federal farm subsidies flow.

26

It's also the best place to look for ways to reduce and refocus government largesse.

Not all welfare programs lack merit. The USDA's $115 billion Food and Nutrition Service, for example, helps farmers by boosting sales of crops and animal foods. It also helps one in seven Americans by providing school lunches and food stamps for low-income children and adults. There's no reason to eliminate these food assistance programs, but like alcohol and tobacco, animal foods should be excluded as ineligible for purchase. This change would shift demand in the low-income demographic—which is particularly at risk for obesity and diabetes—to healthier, lower-fat protein sources. It would also cut indirect support to animal food producers by $36.8 billion and reduce US sales of animal foods by $24.8 billion.

27

The other proposed support change would better align the USDA's spending programs with its own nutritional recommendation that we eat less animal foods. Five USDA programs spend nearly $30 billion yearly supporting US farmers with loans, research, crop insurance, marketing assistance, and help exporting their products.

28

By eliminating the portion of this total spent supporting animal agriculture (i.e., subsidies to growers of livestock and feed crops), we can cut $18.2 billion from the subsidy pool.

29

The reduced demand for meat and dairy caused by a Meat Tax would automatically drive further cuts in subsidies to the animal food industry. For example, state and federal irrigation subsidies pay farmers $15.7 billion yearly to water feed crops. As a result of the decline in consumption, roughly $5 billion of this total is likely to migrate away from supporting animal foods.

30

In total, as we'll see, the Meat Tax and other proposed changes would cut US consumption of animal foods by nearly half, save roughly $184 billion dollars in externalized costs, create a $32 billion cash surplus, shift tens of billions of dollars in support payments to healthier foods, and provide enormous other social benefits.