Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (47 page)

Read Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East Online

Authors: David Stahel

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Modern, #20th Century, #World War II

In Guderian's

panzer group, figures for the number of combat-ready tanks in his divisions vary rather widely, although all denote a striking rate of attrition which was eroding force strengths to critical levels. Even the most optimistic assessment recorded on 7 July in the war diary of the panzer group classed the tanks in the

18th and

3rd Panzer Divisions as being at just 35 per cent combat readiness. The

4th and

17th Panzer Divisions were said to be at 60 per cent combat readiness, while the 10th

Panzer Division was strongest at 80 per cent.

32

Yet, as an example of the difference in figures, the quartermaster's war diary for the panzer group claimed on the same day that the 18th Panzer Division was at only 25 per cent strength and the 17th Panzer Division at 50 per cent.

33

Two days earlier (5 July) the war diary of the XXXXVII Panzer Corps, to which both divisions belonged, claimed the 18th Panzer Division was

at 30 per cent

strength and the 17th Panzer Division at 33 per cent of its starting

total.

34

Obviously there was some confusion regarding the precise figures, possibly stemming from definitions of what constituted ‘combat ready’, but what remains clear is the toll the first two weeks of operations took on the German panzers. Without question the bad roads and dust accounted for most of the high fallout, though reports show that the use of captured Soviet low octane fuel stocks proved highly destructive to German engines and accounted for a further noteworthy share of losses.

35

Although a sizeable percentage of

Army Group Centre's panzer fleet was out of commission by the time they reached the great rivers, the majority of these were not irreparably damaged and therefore not ‘total losses’. The process of undertaking repairs, however, was complicated by the inadequate supply of spare parts and the insufficient resources of field maintenance companies.

Facilities for major overhauls in the field were practically non-existent because they had not been necessary for past blitzkrieg campaigns in Poland, France and the Balkans. In each of these cases a victorious end to hostilities was rapidly achieved, allowing for the trouble-free return of tanks to German factories for major overhauls and rebuilding. In the Soviet Union such measures were impractical, not only because the Red Army remained unbeaten in the field, but because the railways still lagged far behind the advanced panzer groups.

36

The panzer troops were discovering what would soon become the scourge of the whole German army in the east – that their support basis was thoroughly inadequate, and that maintaining effective force levels required desperate ingenuity and improvisation.

In addition to the high fallout of tanks for technical reasons, combat losses or ‘total losses’ represented, according to Guderian's panzer group on 7 July, 10 per cent of his whole panzer fleet.

37

While this is a low figure in comparison with the number of Soviet tanks already destroyed, seen in the light of the small German domestic production and the excessive operational demands placed by Barbarossa on the panzer groups, even low combat losses pushed the remote chance of a blitzkrieg victory further from realisation. In the summer of 1941, the tank represented a

finite resource to the army's striking power, which was steadily eroded in the early weeks of the campaign. This erosion crippled the central instrument required for achieving the strategic plan. Accordingly, even minor Soviet victories over the German panzer arm, like the destruction of 22 German tanks in an ambush north of

Zhlobin on 6 July,

38

assume disproportionate significance for depleting Germany's powerful, but very limited, mechanised weapons. Referring to the previous ambush one German officer noted on 7 July: ‘Our panzers have heavy losses. One company has just one tank which is still serviceable.’

39

It was not only the loss of tanks in the panzer divisions that was impairing their performance. On 6 July the 18th

Panzer Division was deemed ‘no longer fully combat ready’ because of numerous losses in men and material during the two-week uninterrupted march.

40

Three days later the divisional war diary observed: ‘The troops make an exasperated impression. They are missing rest and the high officer losses are noticeable. Combat strength greatly constricted. Weapons in need of

overhauling.’

41

Perhaps the most insightful comment came from the divisional commander,

Major-General Walther Nehring, who even at this early stage cautioned: ‘This situation and its consequences will become unbearable in the future, if we do not want to be destroyed by winning.’

42

Another observer commenting on the men in the

12th Panzer Division stated: ‘Not one of them dared to express a doubt or his own opinion about the war in which they were all involved, even though day after day the corpses of their fellow soldiers – bullet-riddled and torn by shrapnel – became more numerous.’

43

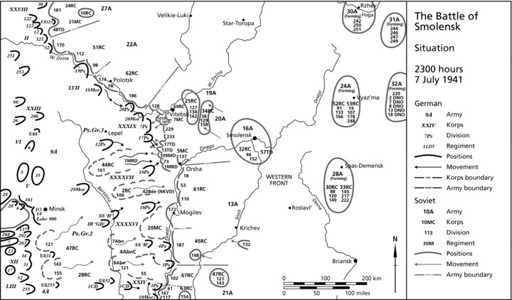

Map 4

Map 4

Dispositions of Army Group Centre 7 July 1941: David M. Glantz,

Atlas of the Battle of Smolensk 7 July– 10 September 1941

As Bock's forces were still moving up to the great rivers, the Soviet High Command (

Stavka

) insisted

Timoshenko launch an offensive with his

20th Army towards

Lepel (see

Map 4

). Spearheading the advance were to be the newly arrived

5th and

7th Mechanised Corps fielding about 1,420 tanks between them, but lacking vital infantry support, anti-aircraft guns and air cover.

44

The counter-stroke was launched on 6 July and initially gained some success with the

7th Panzer Division being pushed out of

Senno,

45

but the cumulative effects of poor concentration, inadequate support and the 7th Panzer Division's skilled anti-tank defence, quickly halted the drive. Successive Soviet counter-attacks failed to break the German lines and effectively decimated the two mechanised corps.

46

On 8 July the Germans re-took Senno with ‘few panzer losses, but heavy losses in the dead and wounded’.

47

The

Lepel counter-attack was clearly a wasteful failure for the Red Army, but its significance should also be seen in the extent to which the battle impacted on the German command, who simply didn't realise Timoshenko possessed the strength for anything so audacious.

48

Before the attack on 6 July

Bock acknowledged that his forces were too widely scattered and that ‘now “a fist has to be made” somewhere’.

49

Yet, on the following day, in the wake of widespread Soviet attacks west of the Dnepr, Bock's plan to redeploy

Vietinghoff's

XXXXVI Corps northwards, to create a powerful ‘fist’ in the centre of the front together with

Lemelsen's

XXXXVII and

Schmidt's

XXXIX Panzer Corps, was judged by Bock to be ‘no longer feasible’.

50

As a result, the Field Marshal resolved to continue the attack on a broad front, which, in spite of his intentions to regroup his forces once the western bank of the

Dnepr was fully secured, never materialised. The dangerous consequence of continuing east on a broad front would become evident in the long drive beyond the Dnepr.

While

Timoshenko expended his available strength in attempting to force the Germans back in the centre of his front, his forces along the

Dvina were left dangerously thin. Holding the long front against Hoth's panzer group was Western Front's

22nd Army which had been unable to eliminate

Kuntzen's small bridgehead at

Disna and was now about to face a concerted attack by Schmidt's XXXIX Panzer Corps at

Ulla. Unlike Guderian's broad advance, Hoth now stripped

Kuntzen's LVII Panzer Corps of the

12th Panzer Division and the 18th Motorised Division (leaving him only the

19th Panzer Division at Disna) and directed them to follow Schmidt's attack, in order to exploit the breakthrough.

51

On 7 July the 20th

Panzer Division supported by the 20th Motorised Division

successfully forced a crossing at

Ulla and then proceeded east to

Vitebsk, which was taken on 9 July.

Hoth's

success effectively broke Timoshenko's left flank and rendered the Soviet defensive position anchored on the

Dvina hopeless. With Soviet forces outmanoeuvred and the operational freedom to exploit the breakthrough, Hoth seemed set for another deep penetration of Soviet lines. Yet the immediate operational opportunities and the seriousness of Western Front's strategic position disguised the fatigue of Hoth's armoured group, which was rapidly exhausting itself and struggling to remain mobile. On 8 July the panzer group's war diary stated that its battles over the past few days had resulted in ‘substantial losses in men and material, including panzers’. Consequently it noted: ‘The resulting losses in officers, panzers and vehicles had to be taken into account, although the mobile divisions would desperately miss them in a further push towards Moscow.’

52

The gravity of the problem was clearly detailed in a report compiled by the panzer group and sent to 4th Panzer Army and Bock's army group command on 8 July. The

document began by pointing out that the daily radio transmissions could not adequately convey to higher command many of the underlying problems slowing down operations and causing difficulties. The report therefore listed eight points of fundamental concern to the panzer group, for which it concluded: ‘The danger therefore exists that in the future, mobile units will be expected to perform duties which they cannot fulfil.’

53

Point one discussed the unsuitability of civilian vehicles, captured French buses and motorcycles (which made up the great majority of 3rd Panzer Group's wheeled transport) for service in the east. They were not robust enough for the roads and conditions, resulting in high fallout rates and constant traffic-jams. The section ended: ‘The fluid advance suffers.’

Point

two referred to the extensive problems brought about by the poor roads which were so sandy and marshy that ‘a march tempo of maximum 10 km per hour is attainable. Every time estimate is questionable.’ The report cited an example where on one stretch 17 hours were needed to drive 110 kilometres. Further delays were caused by having to almost always strengthen bridges over the streams and tributaries that dotted the landscape. It was also stated that overtaking and two-way traffic were ‘often only possible with great difficulty’.

The third point emphasised the problem of conducting operations on a solitary road with troops stretched out in a long column. This limited the breadth of the advance and the capability of getting specialised units, such as engineers or anti-aircraft guns, to the front quickly.

The fourth point stated: ‘The troops, in particular the drivers, are very tired after 14 days of advance.’ The report continued that the bad roads had cost the army its planned rest period and, as a result, a sufficient respite could not be

granted.

Point five highlighted the difference in quality between the motorised and panzer divisions with experience in past campaigns, and those newly formed in the spring of 1941. The new divisions were said to have less experience in the movement of large columns and also less ‘driving skill’. The example of the new 18th Motorised Division was cited that, the report stated, was being expected to perform duties even the experienced units would have great difficulty conducting.

The sixth point noted the panzer group's relatively high losses among officers, particularly among the more experienced and eager officers. A more hesitant approach to the conduct of operations was therefore sometimes evident.

The seventh point referred to the menacing activity of the Soviet air force, which was causing sporadic halts to the advance through the revival of aerial attacks.

The

eighth and final point concerned the nature of opposition the 3rd Panzer Group was meeting from Soviet soldiers. The report stated:

The Russian fights tough and fiercely, attacks continually, is very skilled in defence and on the Dvina is apparently well commanded. Resistance in the countryside constantly resurges. Often the Russian waits, well camouflaged and only when the distance is short does he then open fire.

54