Resident Readiness General Surgery (49 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Abigail K. Tarbox, MD and

Mamta Swaroop, MD, FACS

A healthy 30-year-old female undergoes an uneventful, elective ventral hernia repair under general anesthesia. She goes to the surgical floor, where she receives a hydromorphone PCA for pain control and is kept NPO until return of bowel function. She does well until postoperative day 2, when she develops nausea and vomiting. Her nurse calls you asking what to do. You evaluate the patient. When you arrive at her bedside, you find her sitting up in bed leaning over an emesis bin. She tells you she has been vomiting intermittently for the past 2 hours. Her incision looks benign and her abdomen is not distended. She has infrequent bowel sounds.

1.

What is the best medication to give her to help with her symptoms?

2.

Is this patient’s nausea and vomiting likely due to the lingering effects of anesthesia?

3.

Does this patient need an NG tube?

POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Answers

1.

There are 3 types of afferent nerve inputs that ultimately result in vomiting—input from the vestibular complex, input from the viscera, and input from the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the base of the fourth ventricle. Numerous neurotransmitters are involved in these pathways, although dopamine and serotonin are the most clinically relevant. This is because visceral stimulation and stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone are the most likely causes of nausea in postsurgical patients, both of which are mediated by these 2 neurotransmitters. This helps to explain why the most frequently used anti-emetics following surgery target dopamine and serotonin.

Metoclopramide (Reglan) and promethazine (Phenergan) are the most common dopamine antagonists. Promethazine is especially useful as it is available in both suppository and intravenous forms. Unfortunately, this entire class of medications may cause significant side effects, including orthostatic hypotension and excessive sedation. They can also cause extrapyramidal effects and are therefore strictly contraindicated in patients with Parkinson disease. In addition, promethazine can cause venous sclerosis at the site of administration, while metoclopramide has promotility effects and should not be given to patients with either confirmed or suspected bowel obstruction.

Due to their better side effect profiles, serotonin antagonists have become the primary treatment for a variety of causes of nausea. While side effects of serotonin antagonists are rare, they include headache, diarrhea, hypersensitivity reactions, and QT prolongation. The most common drug in this class is ondansetron (Zofran), which would be an appropriate first-line medical treatment for the case presented.

2.

Nausea and vomiting are not uncommon in the postoperative period. Nausea and vomiting in the first 24 hours after surgery is defined as “early” postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and is usually directly related to the effects of anesthesia. Early PONV occurs in 20% to 30% of patients, is more common in females, and is the number 1 reason for unexpected hospital admission following ambulatory surgery. Early PONV can often be prevented with appropriate chemoprophylaxis in people at high risk for PONV, and if it does develop, it usually resolves with antiemetic treatment alone.

When nausea and vomiting occur more than 24 hours after surgery, it is unlikely to be caused by the lingering effects of anesthesia. Frequent causes are medications (eg, opiates), electrolyte abnormalities (eg, hypokalemia), constipation (often also due to opiates), delayed return of bowel function (aka ileus), and mechanical bowel obstruction (ie, from an anastomotic stricture). However, more serious causes such as infection, acute myocardial infarction, and CNS disturbances can also cause nausea and vomiting and must be ruled out. Always think, “what could kill this patient?” and then rule out the most morbid diagnosis on the differential first. As with most situations, a careful history and physical exam will often guide you to the etiology. In your history, you should ask about the timing of the nausea and vomiting and relationship to meals or medications. Ask about the character of the emesis—if it is bilious, it indicates that duodenal contents have refluxed back through the pylorus and into the stomach. You will also want to know if the patient has passed flatus or had a bowel movement, if there is associated pain, and how many times the patient has vomited.

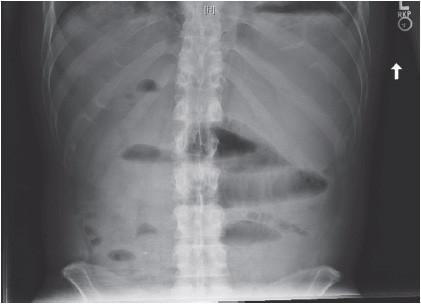

Next, assess the patient’s vital signs and then examine the patient. Abdominal distension is frequently present in ileus and small bowel obstruction. Hypoactive or absent bowel sounds are characteristic of ileus on auscultation of the abdomen, whereas hyperactive bowel sounds are more likely in obstruction. Abdominal plain films will show global dilation of small and large bowel in the case of an ileus (see

Figure 38-1

). An obstruction, on the other hand, will have proximally dilated loops of bowel, with distal decompression and paucity of air in the colon or rectum (see

Figure 38-2

).

Figure 38-1.

Postoperative ileus: radiograph from a patient with postoperative ileus shows gastric distention, distended small bowel loops, and air and stool throughout the colon.

Figure 38-2.

Upright radiograph of a small bowel obstruction shows dilated small bowel and multiple air–fluid levels.

3.

Treatment of PONV depends on the etiology. If you suspect an obstruction or ileus, if the patient has persistent vomiting no matter the cause, or if the patient is at high risk of aspiration, then you should strongly consider placing an NG tube. While uncomfortable and not without its own risks, an NG tube will reduce the chance of aspiration. If you are on the fence about whether

or not an NGT is indicated, a plain film can be particularly helpful—dilated loops of bowel or a dilated stomach indicate that the patient is likely to continue vomiting. In that case, an NG tube would be of benefit. If you feel the patient would benefit from an NG tube, you should alert your senior resident prior to performing this routine but still invasive procedure.

If the symptoms always follow the administration of narcotics, try to minimize their usage and, when appropriate, use alternative pain relievers such as NSAIDs or Tylenol. Standing Tylenol (per rectum if necessary) is effective at reducing the total amount of opiates required, even if it can’t replace them entirely. Antiemetics such as ondansetron can also be given concurrently with narcotics to prophylax against nausea.

While elucidating the diagnosis, a single dose of an antiemetic is often effective to help make the patient more comfortable. Make the patient NPO and remember to restart intravenous fluids or adjust the rate, if still infusing. If you haven’t already checked the electrolytes that day, you should do so and then correct any abnormalities.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

The first-line antiemetic is ondansetron given its superior side effect profile. Second-line agents are metoclopramide and promethazine, although they should not be used in patients with Parkinson disease.

Early PONV is usually due to the lingering effects of anesthesia and can safely be treated with medications alone.

Strongly consider nasogastric tube decompression in patients with persistent vomiting, small bowel obstruction, a large gastric bubble, or those at increased risk for aspiration.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Which antiemetic is a poor choice in a patient with a small bowel obstruction?

A. Ondansetron (Zofran)

B. Metoclopramide (Reglan)

C. Promethazine (Phenergan)

2.

Which is the greatest risk factor for development of

early

PONV in patients undergoing surgery?

A. Long operative time

B. Older age

C. Female gender

3.

Your patient is a frail 80-year-old male who is postoperative day 3 from a small bowel resection. You started him on clear liquids this morning, but in the past hour he has vomited twice. On exam he is distended. What is your next step?

A. Get a KUB.

B. Place an NG tube.

C. Call your senior.

Answers

1.

B

. Metoclopramide (Reglan) is also a promotility agent that should be avoided in bowel obstruction—pushing against the obstruction only worsens the problem.