Resolute (13 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

THIS FRONT PAGE OF THE

Illustrated London News

depicts Franklin and thirteen of his men. All were aboard the

Erebus

, except Crozier. Left right by row: Lieut. Couch (mate), Lieut. Fairholme, C. H. Osmer (Purser), Lieut. Des Voeux (mate), Capt. Crozier (Terror), Capt. Sir John Franklin, Cmdr. Fitzjames, Lieut. Gore, S. Stanley (Surgeon), Lieut. H.T.D. Le Vesconte, Lieut. R. O. Sergeant (mate), James Reid (ice-master), H. D. S. Goodsir (assistant-surgeon).

As

THE DAY

of Franklin's departure drew near, the names Franklin,

Erebus

, and

Terror

echoed throughout England. Surely this was the search that would bring the long-awaited glorious result. (The air of confidence that surrounded Franklin was partially due to the fact that in 1839 two Hudson's Bay Company explorers had completed an expedition that many believed had already charted the way to the Northwest Passage; see note, page 263). The toasts of all London, Sir John and Lady Franklin were honored at dozens of social events. The newspapers seemed to write of nothing else but the impending voyage. “There appears to be but one wish amongst the whole of the inhabitants of this country,” exclaimed the normally staid London

Times

, “that the enterprise in which the officers and crew are about to be engaged may be attended with success.” In another article, the

Times

stated reasons for its obvious optimism: “The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty,” it proclaimed, “have, in every respect, provided most liberally for the comforts of the officers and men of an expedition which may, with the facilities of the screw-propeller, and other advantages of modern science, be attended with great results.” One observer, awed by the acclaim the expedition was receiving even before leaving the dock put it simply: “One would fancy,” he stated in wonderment, “England celebrating Franklin's return rather that his departure.”

He was right. It was indeed a celebration, one that continued to grow right up to the point of departure and included exultations from the most respected officialsâincluding the president of the Geographical Society. “I have the fullest confidence,” stated Roderick Murchison, “that everything will be done for the promotion of science, and for the honor of the British name and navy, that human efforts can accomplish. The name of Franklin alone is, indeed, a national guarantee.” Lady Franklin had done her job well.

On May 19, 1845, more than ten thousand people crammed the docks to see the expedition off and wish it good fortune. Just before boarding, the officers and crew had taken the last opportunity to send their letters to loved ones. Twenty-four-year old James Walter Fairholme, who had been promoted to the rank of lieutenant two years before being assigned to the

Erebus

, had made a point of describing the feelings for Franklin he had already developed: “He has such experience and judgment,” he wrote, “that we all look on his decisions with the greatest respect. I have never felt that the Captain was so much my companion with anyone I have sailed with before.”

It appeared to be a good sign, and perhaps an even better one took place just as the ships left the dock. “Just as they were setting sail,” Franklin's daughter, Eleanor, wrote that “a dove settled on one of the masts, and remained there for some time. Every one was pleased with the good omen.” It was certainly that. But, at the same time, no one throughout the entire expedition's preparation or departure seemed to have attached any significance to the names of the two vessels charged with carrying Franklin to glory:

Erebus

âthe word for the dark region below the earth where the dead must pass to reach Hades, and

Terror

, meaning intense, overpowering fear.

CHAPTER 7.

CHAPTER 7.Vanished

“Expectation darkened into anxietyâanxiety into dread.”

â

Dollar Magazine

I

N

1912,

NORWEGIAN EXPLORER ROALD AMUNDSEN

, who a year earlier had led the first group to reach the South Pole, reflected upon all of the nineteenth-century Arctic explorers who had gone before him. “Few people of the present day,” he wrote, “are capable of appreciating this heroic deed, this brilliant proof of human courage and energy. These men sailed into the heart of the pack, which all previous explorers had regarded as certain death ⦠These men were heroesâheroes in the highest sense.”

The men of the

Erebus

and the

Terror

may or may not have regarded themselves in such heroic terms, but as they cleared the harbor, the cheers of the well-wishers still resounding in their ears, they were, almost to a man, aware that the hopes of all England sailed with them and that theirs was a mission of destiny. “Never, no never shall I forget the emotions called forth by the deafening cheering,” Charles Osmer, the

Erebus's

purser would write. “The suffocating sob of delight mingled with the fearful anticipation of dreary void ⦠could not but impress on every mind the importance and magnitude of the voyage we have entered upon. There is something so thrilling in the true British cheer.”

>

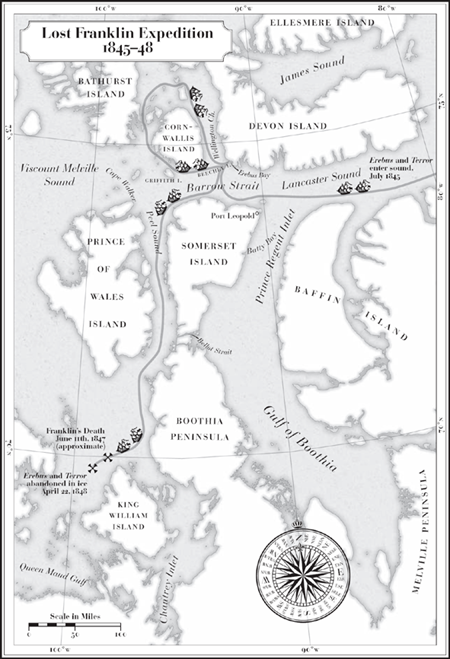

THIS MAP, BASED ON

John Franklin's directive and Inuit testimony gathered in the years following his disappearance, shows the route that the

Erebus

and the

Terror

were assumed to have takenâthrough Lancaster Sound, around Cornwallis Island, through Barrow Strait to the area north and west of King William Island.

The orders that Franklin carried with himâthe last that Barrow would ever issue to a passage-seekerâwere, like all the instructions given to those previously sent out, clear and optimistic. Franklin was to sail to Greenland, proceed on to Baffin Bay, and once having crossed it, move through Lancaster Sound to Barrow Strait. At the Strait's westernmost end he was to steer southâhe would now be in uncharted territoryâfollowing any open waters he could find until he reached the North American mainland. He was then to proceed west along the coastline that Franklin himself had mapped on his Canadian expeditions until he entered Bering Strait, which would lead him to the Pacificâand victory.

To Barrow, his orders were more than instructions. Given how much of the Arctic had already been explored and the capabilities of Franklin's two ships, they were nothing less than a road map that he simply had to follow. He did, however, provide a contingency plan. If, after passing through Barrow Strait, Franklin found his way south blocked by ice or unknown land, he was to seek an alternative route north that Barrow still felt might lead to the Open Polar Sea. It would be these alternative instructions that would play a larger role in the events of the better part of the next fifteen years than anyone could ever have imagined.

By the end of July, Franklin was right on target. He had been able to follow his orders to the letter. Having reached Baffin Bay, he was waiting for conditions to clear before crossing the bay and heading for Lancaster Sound. While waiting, the

Erebus

and the

Terror

were unexpectedly joined by two whaleships, the

Prince of Wales

and the

Enterprise

, and Franklin and his officers were invited to come aboard the

Prince of Wales

for a visit. “Both ships' crews are well, and in remarkable spirits, expecting to finish the operation in good time,” the captain of the

Prince of Wales

noted in his log. “They are made fast to an iceberg with a temporary observatory fixed upon it.” The

Enterprise's

skipper made his own notations, commenting on the fact that Franklin had told him that he had provisions enough for five years and, if he had to, could “make them spin out for seven years.”

AS ANXIETY OVER FRANKLIN

and his men began to grow, publications throughout Great Britain and in the United States began to express their concern. Boston's

Dollar Magazine

adorned the cover of one of its issues with this illustration titled

The Whalers' Last View of Franklins Ships.

The accompanying story emphasized Lady Franklin's early pleadings that a rescue effort be launched.

It was a welcome encounter, and before leaving the whaleship, Franklin reciprocated by asking the two captains to join him on the

Erebus

the next evening. But in the morning, conditions suddenly improved and the

Erebus

and

Terror

weighed anchor. They would never be seen again.

Two years elapsed, years in which Franklin was expected to return any day in triumph. Given the difficulty in communicating over such a long distance from such a remote region, there was no real concernâyet. But by the end of 1847, there was still no news. Public concern began to grow. Where was he? Where were the two greatest ships on the planet? The following spring the first official mention of a rescue mission was made in the House of Commons. Not surprisingly, it was instigated by Jane Franklin. Increasingly, the newspapers and other journals joined in commenting on the national mood. As

Dollar Magazine

proclaimed, “Expectation darkened into anxietyâanxiety into dread.”

By this time the Lords had, to a large degree, turned over affairs dealing with northern exploration to the Arctic Council, an exclusive fraternity of naval officers whose deeds had already made them legendary, men whose names now appeared on capes and straits and other waterways throughout the Arctic. More than anyone else, they could imagine what Franklin, if he was still alive, had to be going through. Each of themâEdward Parry, George Back, John Clark Ross, John Richardson, Frederick Beecheyâhad risked his life to help England triumph in the Arctic. There was no question in their minds: Franklin had to be found. Everything possible had to be done to find him.

The one thing the Admiralty had done was to offer rewardsâ£20,000 to anyone who “might render efficient assistance in saving the lives of Sir John Franklin and his squadron,” and £10,000 for anyone who simply found his ships. But it was not enough. Simply by having disappeared, Franklin had risen in status from hero to godlike figure. Something had to be done; the public and English national pride demanded it.

One man was more than willing to do something. It was John Ross, now nearly seventy years old. From the beginning, he had been the one critic of the Franklin venture. Why, he had asked, was the expedition so large? Repeatedly he had pointed out that in his 1829-33 voyage he had brought only twenty-three men, and they were barely able to sustain themselves. Why, he wanted to know, was Franklin taking such huge vessels? Admittedly they were technological wonders, but as far as Ross was concerned they drew far too much water for Arctic conditions.

In 1845, Ross had supposedly promised Franklin that if the

Erebus

and the

Terror

went missing in the ice, he would return to the Arctic to lead the search-and-rescue mission. Ross was now ready to keep his promise. But the Council turned him down. He was too old, they told him. Instead, plans for a three-pronged rescue effortwere adopted. First, an overland expedition would be mounted to the Canadian northwest. Its mission would be to try to find Franklin by following the MacKenzie River north to the Arctic coast before proceeding eastward along the rim of Wollaston Land and Victoria Land. Franklin's friend and two-time Arctic companion John Richardson was chosen to lead the expedition, a decision applauded by Jane Franklin. She was now spending all of her working hours lobbying for rescue efforts. When Richardson's selection had been announced, she had actually volunteered to join the search, an offer that Richardson diplomatically declined. In one of the many letters she wrote to her husband and placed in the hands of search parties, she explained, “It would have been a less trial to me to come after youâ¦but I thought it my duty and my interest to remainâ¦yet if I thought you to be ill, nothing should have stopped me.” Like every other letter she would dispatch, it was brought back unopened.