Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (31 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

At the end of November, the two SAS squadrons met up with Stirling at Bir Zelten, a new desert base farther west: from there, Paddy Mayne’s men then set out to harass the retreating German forces around Sirte, inflicting further mayhem and taking remarkably few casualties.

But B Squadron, marauding to the west around Tripoli, suffered badly in the December raids. The squadron was operating in a more densely populated area, where many of the local Arabs were distinctly unfriendly and much more likely to tip off the enemy. The Germans, alert to the threat of raids, were now actively hunting down the SAS. In his diary, Rommel noted that his troops were “combing through the district hoping to stumble on a Tommy.” By the end of December, B Squadron had lost more than a dozen men, and three of its six officers had been captured or killed. Reg Seekings narrowly escaped after his unit ran into an enemy patrol. With characteristic bluntness, he put the high casualty rate down to inexperience on the part of B Squadron, whose men had not been “trained up to the proper standards.” But there was another, rather less obvious reason for the series of reverses suffered by B Squadron: an English fascist spy who went by the name of Captain John Richards.

Jim Almonds had run into Richards in the POW camp at Benghazi, and immediately spotted him as a stool pigeon, one of the oldest and nastiest species of spy. The word derives from the practice of tying a single pigeon to a stool in order to lure others: the stool pigeon (also known as a stooge) is a decoy, an informer who infiltrates a group by appearing to be the same as them, while secretly collecting information for the enemy. The prisoners captured in the desert war offered considerable scope for espionage of this sort: a spy introduced among prisoners of war, appearing to be a fellow captive, could extract vital information simply by eavesdropping, asking apparently innocuous questions, and gaining the trust of his compatriots.

For months, Lieutenant Colonel Mario Revetria, the chief of Italian military intelligence in North Africa, had been trying to find out more about the mysterious British raiders who emerged from the desert, often hundreds of miles behind the front lines, to attack airfields and ambush convoys. Rumors abounded about this unit, but there was very little in the way of hard intelligence. Revetria was a canny and experienced intelligence officer who knew that the only way to combat such a force was to discover its secrets. He needed to know who led the SAS, its size, training, and tactics; he needed an informant, an expert stool pigeon. And in Captain John Richards, he found one—a weapon that was far more effective in combating the SAS than any number of soldiers with guns.

Richards’s real name was Theodore John William Schurch: an accountant by trade, a private in the British Army, and a committed fascist. Born in London in 1918 to an English mother and Swiss father who worked as a night porter at the Savoy, Schurch left school at sixteen but possessed what was later described as “innate intelligence and natural shrewdness.” He also had an acute persecution complex. “Ever since I can remember I have been looked at askance on account of my foreign name,” he later said, by way of exculpation. “The result was that my mind became warped and distorted at an early age.” Working as a junior accountant for Lancegaye Safety Glass in Wembley, he met Irene Page, the company’s twenty-three-year-old telephone operator, a young woman with a “large well formed bust” and extreme right-wing views. Every Saturday, she dressed in fascist uniform—black shirt, gray flannel skirt, tie, and beret—to meet up with fellow right-wing fanatics. Irene introduced Schurch to a network of suburban English fascists. Although initially he had been chiefly interested in Irene Page’s bust, he was instantly attracted to the ideology of fascism. At one of the meetings he met Oswald Mosley, the leader of the British Union of Fascists. At another clandestine party gathering in Willesden, he was introduced to an Italian Blackshirt named Bianchi, owner of a Cardiff export firm, who spoke perfect English. Bianchi told Schurch that the Italian fascists had their own secret service, and suggested that he might make an ideal recruit.

The idea of becoming a secret agent took root. In 1936, at the behest of Bianchi, he enlisted in the Royal Army Service Corps and trained as an army driver; a year later, again at the suggestion of his fascist friends, he volunteered for deployment to Palestine. There he began to pass military information to a man named Homis, the Arab owner of the General Motors concession in Palestine, who wore gold rings and a thin dark mustache. In return, Schurch was paid in cash—small amounts at first, but gradually more. As a driver at staff headquarters, he was in a position to glean all sorts of information of interest to both the Arab intelligence service and its Nazi allies: troop deployments, matériel shipments, and the travel plans of senior officers. “In my small way I was helping the fascist movement,” he later said. He was also developing a “taste for expensive pleasure.” Schurch’s wartime comrades remember him as an easygoing character who liked to gossip and always seemed to have plenty of money. In 1941, Schurch’s unit was deployed to Egypt. At the urging of Homis, he requested a frontline posting with the intention of crossing over to the Italian side at the first opportunity. He was finally sent to Tobruk; two days after his arrival the port fell to the Germans, and he was captured along with hundreds of other British soldiers. In the prisoner-of-war camp at Benghazi, he asked to see an officer of Italian military intelligence. The Italians made inquiries, and a few days later Schurch was brought before Colonel Mario Revetria. The Italian intelligence chief swiftly realized that the talkative little man chain-smoking in his tent might prove exceptionally useful, and took him to dinner in the officers’ mess.

On September 13, Schurch was dressed in the uniform of a captain, supposedly in the Inter-Services Liaison Department, and sent back to Benghazi, where a large number of newly captured POWs were being held after the failed Tobruk and Benghazi raids in the preceding days. Schurch was an ugly man, with “a shrunken face and crooked, protruding teeth,” but with his hair slicked back and his blond mustache neatly trimmed he could easily pass for an officer. In the confusion following the abortive raids, none of the prisoners—with the exception of Jim Almonds—paused to wonder whether the friendly Captain John Richards was really who he said he was. Schurch returned to Revetria with intriguing information: some of the POWs were members of “a special unit of the LRDG, later known as the SAS.”

Revetria was “very much interested in the SAS,” and Schurch was ordered to return to the POW camp and gather “all information respecting this kind of unit.” The SAS had perfected the art of slipping behind the front line by driving around it; Schurch found he could slip back through British-held territory simply by being British and wearing an officer’s uniform. Pretending to be an escaped prisoner of war, he crossed the lines at Alamein, gathered information for Revetria on Allied lines of communication, and then returned; he remained behind after Benghazi fell to the British, mixed with the town’s new occupiers, and then once again crossed over to the Axis side. A delighted Revetria rewarded him with money, wine, the best Italian cigarettes, and his own villa.

With the Battle of Alamein, the advance of the Eighth Army, and the series of raids by the SAS, Captain John Richards was deployed once more, to infiltrate and extract information from the captured men of B Squadron. “During this time 2 or 3 patrols of the Special Air Service were captured,” Schurch later explained. “Colonel Revetria made it my responsibility to get information from all prisoners of the SAS. I mixed with three officers and also other ranks of these captured patrols, and from information received in this manner, we found where other patrols were located, and also their strength. From the information received we were able to capture two other patrols, and acquired information as to the operations of other patrols in that area in the near future.” The SAS had demonstrated that it could defend itself militarily in the harshest conditions; the greatest threat to the unit, however, had come from a spy who looked and behaved like an English officer.

—

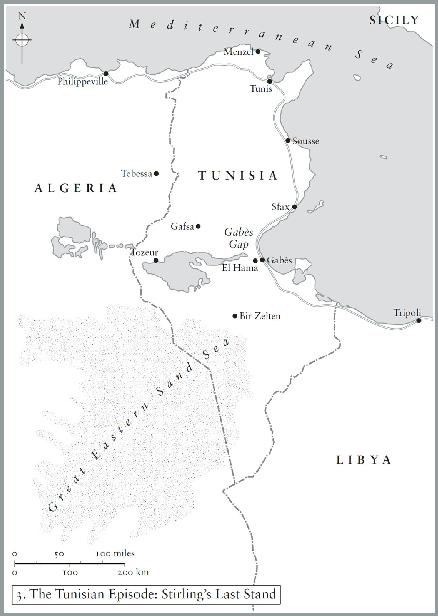

The final chapter of the desert war was about to open, and Stirling was determined to write himself into it, with a bold act of devilry that would demonstrate the prowess of his force once and for all, guarantee the future of the regiment, and ensure a major role for the SAS in the next phase of the war in Europe. He proposed to lead his forces west to harry the Germans and disrupt their communication lines as they retreated into Tunisia, while simultaneously gathering intelligence that might reveal whether Rommel intended to make a stand on the Mareth Line, the string of fortifications built originally by France to defend Tunisia against attacks from Libya. The elegant Lieutenant Harry Poat would lead one group to attack targets west of Tripoli—at the specific request of Montgomery, who was determined to prevent the retreating Germans from organizing an orderly destruction of the port—the French SAS would raid between Gabès and Sfax on the Tunisian coast, and Mayne would operate around the Mareth Line. But, for himself, Stirling had an even more dramatic goal in mind: he would drive northwest, pass

through

the retreating German lines, and then link up with the advancing First Army. In between the two Allied armies lay largely uncharted desert, a huge force of Axis troops, and an enormous, impassable salt marsh. Stirling told Pleydell that he intended to drive “straight across to the south of the fighting zone from one front to the other,” adding that “the journey would give him a good idea of the nature of the country for future operations.” It might establish the possibility of maneuvering an armored division behind the retreating Germans.

The mission might yield important intelligence. But it was also a stunt, a calculated feat of military theater: the opportunity to become the first unit of desert rats to greet approaching American forces was, Stirling later admitted, “irresistible.” Success might lead to further expansion of the regiment, perhaps to brigade status; in Stirling’s imagination the SAS might even swell to three separate regiments, operating in the eastern Mediterranean, Italy, and Nazi-occupied Europe.

Pleydell observed Stirling with a doctor’s eye, and did not like what he saw. The SAS commander “was not looking too fit,” he reflected. Stirling’s desert sores had become so badly infected that he had been hospitalized in Cairo for several days. His migraines had returned, exacerbated by solar conjunctivitis, an eye infection caused by a combination of flying sand and blazing sun. Stirling had taken to wearing sunglasses to protect his eyes, which gave him an oddly gangsterish appearance. Pleydell’s efforts to persuade Stirling to bathe his eyes were politely ignored. He seemed dangerously thin, worn down by his multiplying responsibilities, not least the creation of another, parallel SAS regiment.

For months, Stirling had been lobbying for a second SAS regiment to complement the first. At the end of 1942, approval was finally granted, and 2SAS came into being, under the command of David’s brother Bill Stirling, a lieutenant colonel in the Scots Guards and former commando who shared his brother’s vision for the unit. Bill Stirling had been in command of 62 Commando, also known as the Small Scale Raiding Force, formed to carry out raids in the English Channel. Late in 1942, after being sent to Algeria, 62 Commando was disbanded, and Bill began lobbying Allied Forces HQ for permission to raise a second SAS regiment. The second regiment was attached to the First Army in Algeria, and began recruiting and training at a new base in Philippeville, in northwest Algeria. What had begun as a single, small, semi-private army had spawned an ever-expanding family of special forces, including additional French troops, a unit of tough Greek fighters known as the Greek Sacred Squadron (after the Sacred Band of Thebes), and the Special Boat Squadron. The SAS idea was bearing more fruit than one man could easily carry. Stirling had always been a peculiar mixture of parts: a born organizer who disliked administration, a man of action with limited physical stamina, an officer of vaulting ambition who now saw his creation expanding in ways he had not anticipated and could not fully control. His determination to get back to the desert may have reflected, in part, a desire to escape the responsibilities mounting up on his desk.

To reach the First Army, Stirling’s party would have to skirt the Great Eastern Sand Sea, stretching out from Algeria into Tunisia, and then pass though the Gabès Gap, a natural bottleneck between the Mediterranean and the vast and impenetrable salt marshes to the west. All traffic heading for the coast had to pass through the gap, which was still in German hands and only five miles wide at its narrowest point. Additional jeeps would be brought along simply to carry fuel, and then abandoned en route.

At sunrise on January 16, 1943, Stirling’s column of five jeeps and fourteen men set off from Bir Zelten, preceded by a French unit under Augustin Jordan. Stirling’s force included the navigator Mike Sadler, Johnny Cooper, and a thirty-one-year-old French sergeant, Freddie Taxis, who spoke Arabic. There was a strong possibility of encountering hostile local tribesmen, and an interpreter might prove essential.