Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (109 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

During swallowing, the nasal and oral parts are separated by the soft palate and the

uvula

.

The laryngopharynx

The laryngeal part of the pharynx extends from the oropharynx above and continues as the oesophagus below, i.e. from the level of the 3rd to the 6th cervical vertebrae.

Structure

The walls of the pharynx contain several types of tissue.

Mucous membrane lining

The mucosa varies slightly in the different regions. In the nasopharynx it is continuous with the lining of the nose and consists of ciliated columnar epithelium; in the oropharynx and laryngopharynx it is formed by tougher stratified squamous epithelium, which is continuous with the lining of the mouth and oesophagus. This lining protects underlying tissues from the abrasive action of foodstuffs passing through during swallowing.

Submucosa

The layer of tissue below the epithelium (the submucosa) is rich in mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (

MALT, p. 133

), involved in protection against infection. Tonsils are masses of MALT that bulge through the epithelium. Some glandular tissue is also found here.

Smooth muscle

The pharyngeal muscles help to keep the pharynx permanently open so that breathing is not interfered with. Sometimes in sleep, and particularly if sedative drugs or alcohol have been taken, the tone of these muscles is reduced and the opening through the pharynx can become partially or totally obstructed. This contributes to snoring and periodic wakenings, which disturb sleep.

Constrictor muscles are responsible for constricting the pharynx during swallowing, pushing food and fluid into the oesophagus.

Blood and nerve supply

Blood is supplied to the pharynx by several branches of the facial artery. The venous return is into the facial and internal jugular veins.

The nerve supply is from the pharyngeal plexus, formed by parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves. Parasympathetic supply is by the

vagus

and

glossopharyngeal

nerves. Sympathetic supply is by nerves from the

superior cervical ganglia

(

p. 168

).

Functions

Passageway for air and food

The pharynx is involved in both the respiratory and the digestive systems: air passes through the nasal and oral sections, and food through the oral and laryngeal sections.

Warming and humidifying

By the same methods as in the nose, the air is further warmed and moistened as it passes through the pharynx.

Taste

There are olfactory nerve endings of the sense of taste in the epithelium of the oral and pharyngeal parts.

Hearing

The auditory tube, extending from the nasopharynx to each middle ear, allows air to enter the middle ear. Satisfactory hearing depends on the presence of air at atmospheric pressure on each side of the

tympanic membrane

(eardrum,

p. 187

).

Protection

The lymphatic tissue of the pharyngeal and laryngeal tonsils produces antibodies in response to antigens, e.g. bacteria (

Ch. 15

). The tonsils are larger in children and tend to atrophy in adults.

Speech

The pharynx functions in speech; by acting as a resonating chamber for sound ascending from the larynx, it helps (together with the sinuses) to give the voice its individual characteristics.

Larynx

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

describe the structure and function of the larynx

outline the physiology of speech generation.

Position

The larynx or ‘voice box’ links the laryngopharynx and the trachea. It lies at the level of the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae. Until puberty there is little difference in the size of the larynx between the sexes. Thereafter, it grows larger in the male, which explains the prominence of the ‘Adam’s apple’ and the generally deeper voice.

Structures associated with the larynx

Superiorly

– the hyoid bone and the root of the tongue

Inferiorly

– it is continuous with the trachea

Anteriorly

– the muscles attached to the hyoid bone and the muscles of the neck

Posteriorly

– the laryngopharynx and 3rd to 6th cervical vertebrae

Laterally

– the lobes of the thyroid gland.

Structure

Cartilages

The larynx is composed of several irregularly shaped cartilages attached to each other by ligaments and membranes. The main cartilages are:

|

| |

| • 1 epiglottis. | elastic fibrocartilage |

The thyroid cartilage

(

Figs 10.5

and

10.6

). This is the most prominent of the laryngeal cartilages. Made of hyaline cartilage, it lies to the front of the neck. Its anterior wall projects into the soft tissues of the front of the throat, forming the

laryngeal prominence

or Adam’s apple, which is easily felt and often visible in adult males. The anterior wall is partially divided by the

thyroid notch

. The cartilage is incomplete posteriorly, and is bound with ligaments to the hyoid bone above and the cricoid cartilage below.

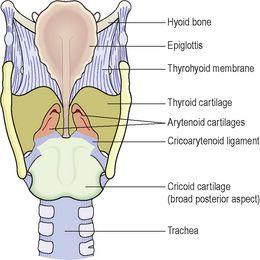

Figure 10.5

Larynx

– viewed from behind.

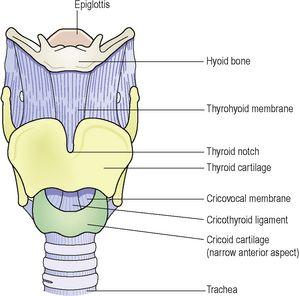

Figure 10.6

Larynx

– viewed from the front.

The upper part of the thyroid cartilage is lined with stratified squamous epithelium like the larynx, and the lower part with ciliated columnar epithelium like the trachea. There are many muscles attached to its outer surface.

The thyroid cartilage forms most of the anterior and lateral walls of the larynx.

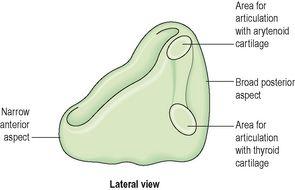

The cricoid cartilage (

Fig. 10.7

)

This lies below the thyroid cartilage and is also composed of hyaline cartilage. It is shaped like a signet ring, completely encircling the larynx with the narrow part anteriorly and the broad part posteriorly. The broad posterior part articulates with the arytenoid cartilages and with the thyroid cartilage. It is lined with ciliated columnar epithelium and there are muscles and ligaments attached to its outer surface (

Fig. 10.7

). The lower border of the cricoid cartilage marks the end of the upper respiratory tract.