Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (148 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

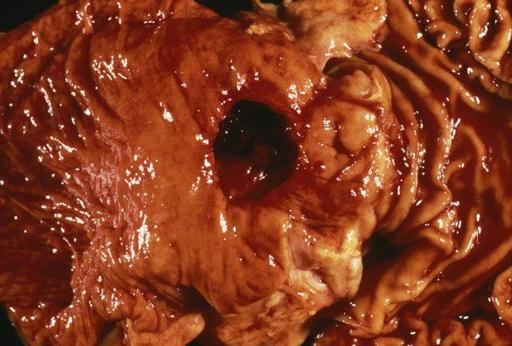

Figure 12.46

Oesophageal varices.

Inflammatory and infectious conditions

Acute oesophagitis

This arises after caustic materials are swallowed and also if immunocompromised people acquire severe fungal infections, typically candidiasis (

p. 311

), or viral infections, e.g.

Herpes simplex

.

Dysphagia

(difficulty in swallowing) is usually present. Following severe injury, healing causes fibrosis, and there is a risk of oesophageal stricture developing later, as the fibrous tissue shrinks.

Reflux oesophagitis

This condition, the commonest cause of indigestion (or ‘heartburn’), is caused by persistent regurgitation of acidic gastric juice into the oesophagus, causing irritation, inflammation and painful ulceration. Haemorrhage occurs when blood vessels are eroded. Persistent reflux leads to chronic inflammation and if damage is extensive, secondary healing with fibrosis occurs. Shrinkage of mature fibrous tissue may cause stricture of the oesophagus. This condition sometimes gives rise to Barrett’s oesophagus (see below). Reflux of gastric contents is associated with:

•

increase in the intra-abdominal pressure, e.g. in pregnancy, constipation and obesity

•

high acid content of gastric juice

•

low levels of secretion of the hormone gastrin, leading to reduced sphincter action at the lower end of the oesophagus

•

the presence of hiatus hernia (

p. 321

).

Barrett’s oesophagus

This condition develops after long-standing reflux oesophagitis. Columnar cells resembling those found in the stomach replace the squamous epithelium of the lower oesophagus and this is a premalignant state carrying an increased risk of subsequent malignancy.

Achalasia

This problem tends to occur in young adults. Peristalsis of the lower oesophagus is impaired and the lower oesophageal sphincter fails to relax during swallowing, causing dysphagia, regurgitation of gastric contents and aspiration pneumonia. The oesophagus becomes dilated and the muscle layer hypertrophies. Autonomic nerve supply to the oesophageal muscle is abnormal, but the cause is not known.

Tumours of the oesophagus

Benign tumours are rare, accounting for only 5% of oesophageal tumours.

Malignant tumours

These occur more often in males than females. They are most common in the lower oesophagus but can arise at any level. Both types of tumour, described below, tend to begin as an ulcer that spreads round the circumference causing a stricture that results in dysphagia. By the time of diagnosis, local spread has usually occurred and the prognosis is very poor.

Squamous carcinoma

usually affects the middle third and is associated with some dietary deficiencies, regular consumption of very hot food, tannic acid (in tea and sorghum) and possibly viruses. The worldwide incidence varies considerably. In developed countries, long-term alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking are also implicated.

Adenocarcinoma

develops from Barrett’s oesophagus (see above).

Congenital abnormalities

The most common congenital abnormalities of the oesophagus are:

•

oesophageal atresia

, in which the lumen is narrow or blocked

•

tracheo-oesophageal fistula

, in which there is an opening (fistula) between the oesophagus and the trachea through which milk or regurgitated gastric contents are aspirated.

One or both abnormalities may be present. The causes are unknown.

Diseases of the stomach

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

compare the main features of chronic and acute gastritis

discuss the pathophysiology of peptic ulcer disease

describe the main tumours of the stomach and their consequences

define the term congenital pyloric stenosis.

Gastritis

Inflammation of the stomach can be an acute or chronic condition.

Acute gastritis

This is usually a response to irritant drugs or alcohol. The drugs most commonly implicated are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including aspirin, even at low doses, although many others may also be involved. Other causes include the initial response to

Helicobacter pylori

infection (see below) and severe physiological stress, e.g. in extensive burns and multiple organ failure.

There are varying degrees of severity. Mild cases can be asymptomatic or may present with nausea and vomiting associated with inflammatory changes of the gastric mucosa. Erosions can also occur, which are characterised by tissue loss affecting the superficial layers of the gastric mucosa. In more serious cases, there are multiple erosions, which may result in life-threatening haemorrhage causing

haematemesis

(vomiting of frank blood or black ‘coffee grounds’ when there has been time for digestion of blood to occur) and

melaena

(passing black tarry faeces), especially in elderly people.

The outcome depends on the extent of the damage. In many cases recovery is uneventful after the cause is removed. Where there has been extensive tissue damage, healing is by fibrosis causing reduced elasticity and peristalsis.

Chronic gastritis

Chronic gastritis is a milder longer-lasting condition. It is usually associated with

Helicobacter pylori

but is sometimes due to autoimmune disease or chemical injury. It is more common in later life.

Helicobacter

-associated gastritis

The microbe

Helicobacter pylori

can survive in the gastric mucosa and is commonly associated with gastric conditions, especially chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.

Autoimmune chronic gastritis

This is a progressive disease. Destructive inflammatory changes that begin on the surface of the mucous membrane may extend to affect its whole thickness, including the gastric glands. When this stage is reached, secretion of hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor are markedly reduced. The antigens are the gastric parietal cells and the intrinsic factor they secrete. When these cells are destroyed as a result of this abnormal autoimmune condition, the inflammation subsides. The initial causes of the autoimmunity are not known but there is a familial predisposition and an association with thyroid disorders. Secondary consequences include:

•

pernicious anaemia due to lack of intrinsic factor (

p. 67

)

•

increased risk of cancer of the stomach.

Peptic ulceration

Ulceration involves the full thickness of the gastrointestinal mucosa (

Fig. 12.47

). It is caused by disruption of the normal balance between the corrosive effect of gastric juice and the protective effect of mucus on the gastric epithelial cells. It may be viewed as an extension of the gastric erosions found in acute gastritis. The most common sites for ulcers are the stomach and the first few centimetres of the duodenum. More rarely they occur in the oesophagus and round the anastomosis of the stomach and small intestine, following gastrectomy. The underlying causes are not known but, if gastric mucosal protection is impaired, the epithelium can be exposed to gastric acid causing the initial cell damage that leads to ulceration. The main protective mechanisms are: a good blood supply, adequate mucus secretion and efficient epithelial cell replacement.