Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (72 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

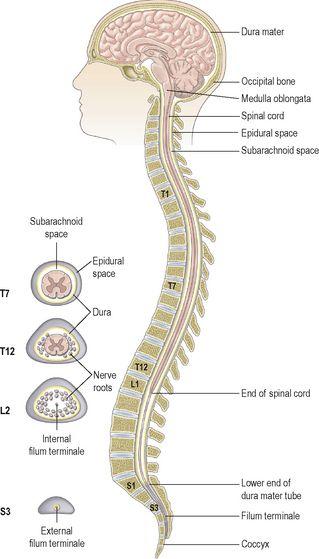

Figure 7.26

The meninges covering the spinal cord

. Each cut away to show the underlying layers.

Figure 7.27

Section of the vertebral canal showing the epidural space.

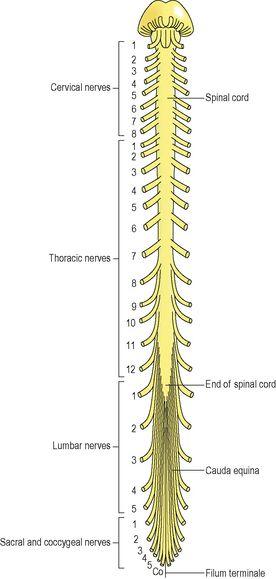

Except for the cranial nerves, the spinal cord is the nervous tissue link between the brain and the rest of the body (

Fig. 7.28

). Nerves conveying impulses from the brain to the various organs and tissues descend through the spinal cord. At the appropriate level they leave the cord and pass to the structure they supply. Similarly, sensory nerves from organs and tissues enter and pass upwards in the spinal cord to the brain.

Figure 7.28

The spinal cord and spinal nerves.

Some activities of the spinal cord are independent of the brain and are controlled at the level of the spinal cord by

spinal reflexes

. To facilitate these, there are extensive neurone connections between sensory and motor neurones at the same or different levels in the cord.

The spinal cord is incompletely divided into two equal parts, anteriorly by a short, shallow

median fissure

and posteriorly by a deep narrow septum, the

posterior median septum

.

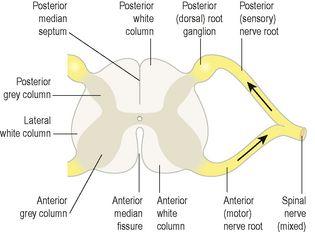

A cross-section of the spinal cord shows that it is composed of grey matter in the centre surrounded by white matter supported by neuroglia.

Figure 7.29

shows the parts of the spinal cord and the nerve roots on one side. The other side is the same.

Figure 7.29

A section of the spinal cord showing nerve roots on one side.

Grey matter

The arrangement of grey matter in the spinal cord resembles the shape of the letter H, having

two posterior

,

two anterior

and

two lateral columns

. The area of grey matter lying transversely is the

transverse commissure

and it is pierced by the central canal, an extension from the fourth ventricle, containing cerebrospinal fluid. The nerve cell bodies may be:

•

sensory neurones

, which receive impulses from the periphery of the body

•

lower motor neurones

, which transmit impulses to the skeletal muscles

•

connector neurones

, also known as interneurones linking sensory and motor neurones, at the same or different levels, which form spinal reflex arcs.

At each point where nerve impulses are transmitted from one neurone to another, there is a synapse (

p. 141

).

Posterior columns of grey matter

These are composed of cell bodies that are stimulated by sensory impulses from the periphery of the body. The nerve fibres of these cells contribute to the formation of the white matter of the cord and transmit the sensory impulses upwards to the brain.

Anterior columns of grey matter

These are composed of the cell bodies of the lower motor neurones that are stimulated by the upper motor neurones or the connector neurones linking the anterior and posterior columns to form reflex arcs.

The

posterior root

(

spinal

)

ganglia

are formed by the cell bodies of the sensory nerves.

White matter

The white matter of the spinal cord is arranged in three

columns

or

tracts

; anterior, posterior and lateral. These tracts are formed by sensory nerve fibres ascending to the brain, motor nerve fibres descending from the brain and fibres of connector neurones.

Tracts are often named according to their points of origin and destination, e.g. spinothalamic, corticospinal.

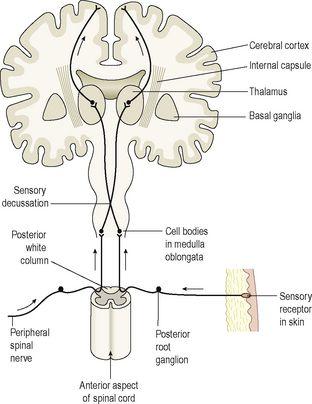

Sensory nerve tracts in the spinal cord

Neurones that transmit impulses towards the brain are called sensory (afferent, ascending). There are two main sources of sensation transmitted to the brain via the spinal cord.

1.

The skin

. Sensory receptors (nerve endings) in the skin, called

cutaneous receptors

, are stimulated by pain, heat, cold and touch, including pressure. Nerve impulses generated are conducted by three neurones to the sensory area in the

opposite hemisphere of the cerebrum

where the sensation and its location are perceived (

Fig. 7.30

). Crossing to the other side, or decussation, occurs either at the level of entry into the cord or in the medulla.

2.

The tendons, muscles and joints

. Sensory receptors are specialised nerve endings in these structures, called

proprioceptors

, and they are stimulated by stretch. Together with impulses from the eyes and the ears they are associated with the maintenance of balance and posture and with perception of the position of the body in space. These nerve impulses have two destinations:

–

by a three-neurone system, the impulses reach the sensory area of the opposite hemisphere of the cerebrum

–

by a two-neurone system, the nerve impulses reach the cerebellar hemisphere on the same side.

Figure 7.30

A sensory nerve pathway from the skin to the cerebrum.

Table 7.1

summarises the main sensory pathways.

Table 7.1

Sensory nerve impulses: origins, routes, destinations

| Receptor | Route | Destination |

|---|---|---|

| Pain, touch, temperature | Neurone 1 – to spinal cord by posterior root Neurone 2 – decussation on entering spinal cord then in anterolateral spinothalamic tract to thalamus Neurone 3 – | to parietal lobe of cerebrum |

| Touch, proprioceptors | Neurone 1 – to medulla in posterior spinothalamic tract Neurone 2 – decussation in medulla, transmission to thalamus Neurone 3 – | to parietal lobe of cerebrum |

| Proprioceptors | Neurone 1 – to spinal cord Neurone 2 – | no decussation, to cerebellum in posterior spinocerebellar tract |

Motor nerve tracts in the spinal cord

Neurones that transmit nerve impulses away from the brain are motor (efferent or descending) neurones. Motor neurone stimulation results in:

•

contraction of skeletal (voluntary) muscle

•

contraction of smooth (involuntary) muscle, cardiac muscle and the secretion by glands controlled by nerves of the autonomic nervous system (

p. 167

).

Voluntary muscle movement

The contraction of the muscles that move the joints is, in the main, under conscious (voluntary) control, which means that the stimulus to contract originates at the level of consciousness in the cerebrum. However, skeletal muscle activity is regulated by output from the midbrain, brain stem and cerebellum. This involuntary activity is associated with coordination of muscle activity, e.g. when very fine movement is required and in the maintenance of posture and balance.

Efferent nerve impulses are transmitted from the brain to other parts of the body via bundles of nerve fibres (tracts) in the spinal cord. The

motor pathways

from the brain to the muscles are made up of two neurones (see

Fig. 7.22

). These pathways, or tracts, are either:

•

pyramidal (corticospinal)

•

extrapyramidal (

p. 149

).

The upper motor neurone

This has its cell body (Betz’s cell) in the primary motor area of the cerebrum. The axons pass through the internal capsule, pons and medulla. In the spinal cord they form the lateral corticospinal tracts of white matter and the fibres synapse with the cell bodies of the lower motor neurones in the anterior columns of grey matter. The axons of the upper motor neurones make up the pyramidal tracts and decussate in the medulla oblongata, forming the pyramids.

The lower motor neurone

This has its cell body in the anterior horn of grey matter in the spinal cord. Its axon emerges from the spinal cord by the anterior root, joins with the incoming sensory fibres and forms the mixed spinal nerve that passes through the intervertebral foramen. Near its termination in skeletal muscle the axon branches into many tiny fibres, each of which is in close association with a sensitive area on the wall of a muscle fibre known as a

motor end plate

(

Fig. 16.56

,

p. 411

). The motor end plates of each nerve and the muscle fibres they supply form a

motor unit

(see

Fig. 16.57

,

p. 411

). The neurotransmitter that transmits the nerve impulse across the neuromuscular junction (synapse) to stimulate the muscle fibre is

acetylcholine

. Motor units contract as a whole and the strength of the muscle contraction depends on the number of motor units in action at any time.