Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (152 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

An abnormally large opening in the diaphragm allows a pouch of stomach to ‘roll’ upwards into the thorax beside the oesophagus. This is associated with obesity and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Sliding hiatus hernia

Part of the stomach is pulled upwards into the thorax. The abnormality may be caused by shrinkage of fibrous tissue formed during healing of a previous oesophageal injury. The sliding movement of the stomach in the oesophageal opening is due to shortening of the oesophagus by muscular contraction during swallowing.

Peritoneal hernia

A loop of bowel may herniate through the epiploic foramen (of Winslow,

Fig. 12.3A

), the opening in the lesser omentum that separates the greater and lesser peritoneal sacs.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Incomplete formation of the diaphragm, usually on the left side, allows abdominal organs such as the stomach and loops of intestine into the thoracic cavity, preventing normal development of the fetal lungs.

Volvulus

This occurs when a loop of bowel twists occluding its lumen resulting in obstruction. It is usually accompanied by

strangulation

, where there is interruption of the blood supply causing gangrene. It occurs in parts of the intestine that are attached to the posterior abdominal wall by a long double fold of visceral peritoneum, the mesentery. The most common site in adults is the sigmoid colon and in children the small intestine. Predisposing factors include:

•

an unusually long mesentery

•

heavy loading of the sigmoid colon with faeces

•

a slight twist of a loop of bowel, causing gas and fluid to accumulate and promote further twisting

•

adhesions formed following surgery or peritonitis.

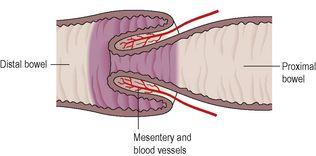

Intussusception

In this condition a length of intestine is invaginated into itself causing intestinal obstruction (

Fig. 12.52

). It occurs most commonly in children when a piece of terminal ileum is pushed through the ileocaecal valve. The overlying mucosa bulges into the lumen, creating a partial obstruction and a rise in pressure inside the intestine proximal to the swelling. Strong peristaltic waves develop in an attempt to overcome the partial obstruction. These push the swollen piece of bowel into the lumen of the section immediately distal to it, creating the intussusception. The pressure on the veins in the invaginated portion is increased, causing congestion, further swelling, ischaemia and possibly gangrene. Complete intestinal obstruction may occur. In adults tumours that bulge into the lumen, e.g. polyps, together with the strong peristalsis, may be the cause.

Figure 12.52

Intussusception.

Intestinal obstruction

This is not a disease in itself. The following is a summary of the effects and main causes of obstruction with some examples.

Mechanical causes of obstruction

These include:

•

constriction or blockage of the intestine by, for example, strangulated hernia, intussusception, volvulus, peritoneal adhesions; partial obstruction (narrowing of the lumen) may suddenly become complete

•

stenosis and thickening of the intestinal wall, e.g. in diverticulosis, Crohn’s disease and malignant tumours; there is usually a gradual progression from partial to complete obstruction

•

obstruction by, for example, a large gallstone or a tumour growing into the lumen

•

pressure on the intestine from outside, e.g. a large tumour in any pelvic or abdominal organ, such as a uterine fibroid; this is most likely to occur inside the confined space of the bony pelvis.

Neurological causes of obstruction

Partial or complete loss of peristaltic activity produces the effects of obstruction.

Paralytic ileus

is the most common form. The mechanisms are not clear but there are well-recognised predisposing conditions including major surgery requiring considerable handling of the intestines and peritonitis.

Secretion of water and electrolytes continues although intestinal mobility is lost and absorption impaired. This causes distension and electrolyte imbalance, leading to hypovolaemic shock.

Vascular causes of obstruction

When the blood supply to a segment of bowel is cut off, ischaemia is followed by infarction and gangrene. The damaged bowel becomes unable to function. The causes may be:

•

atheromatous changes in the blood vessel walls, with thrombosis (

p. 113

)

•

embolism (

p. 113

)

•

mechanical obstruction of the bowel, e.g. strangulated hernia (

p. 321

).

Effects of intestinal obstruction

Symptoms include abdominal pain, vomiting and constipation. When the upper gastrointestinal tract is affected vomiting may be profuse, although it may be absent in lower bowel obstruction. There are neither bowel sounds present nor passing of flatus (wind) as peristalsis ceases. Without treatment, irrespective of the cause, this condition is fatal.

Malabsorption

Impaired absorption of nutrients and water from the intestines is not a disease in itself, but the result of abnormal changes in one or more of the following:

•

villi in the small intestine, e.g. coeliac disease, tropical sprue (see below)

•

digestion of food

•

absorption or transport of nutrients from the small intestine.

Intestinal conditions that impair normal digestion and/or absorption and transport of nutrients include:

•

extensive resection of the small intestine

•

‘blind loop syndrome’ where there is microbial overgrowth in a blind end of intestine following surgery

•

lymphatic obstruction by diseased or absent (following surgical excision) lymph nodes.

Coeliac disease

This disease is the main cause of malabsorption in Western countries. It is due to an abnormal, genetically determined immunological reaction to the protein gluten, present in wheat. When it is removed from the diet, recovery is complete. There is marked villous atrophy, especially in the jejunum, and malabsorption characterised by the passage of loose, pale-coloured, fatty stools (

steatorrhoea

).

There may be abnormal immune reaction to other antigens. Atrophy of the spleen is common and malignant lymphoma of the small intestine is a rarer consequence. It often presents in infants after weaning but can affect people of any age.

Tropical sprue

This disease is endemic in subtropical and tropical countries except Africa. After visiting an endemic area most travellers suffering from sprue recover, but others may not develop symptoms until months or even years later.

There is partial villous atrophy with malabsorption, chronic diarrhoea, severe wasting and pernicious anaemia due to deficient absorption of vitamin B

12

and folic acid. The cause is unknown but it may be that bacterial growth in the small intestine is a factor.

Diseases of the pancreas

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

compare and contrast the causes and effects of acute and chronic pancreatitis

outline the main pancreatic tumours and their consequences.

Acute pancreatitis

Proteolytic enzymes produced by the pancreas are secreted in inactive forms, which are not activated until they reach the intestine; this protects the pancreas from digestion by its own enzymes. If these precursor enzymes are activated while still in the pancreas, pancreatitis results. The severity of the disease is directly related to the amount of pancreatic tissue destroyed.

Mild forms are more common and damage only those cells near the ducts. Recovery is usually complete.

Severe forms cause widespread damage with necrosis and haemorrhage. Common complications include infection, suppuration, and local venous thrombosis. Pancreatic enzymes, especially amylase, enter and circulate in the blood, causing similar damage to other structures. In severe cases there is a high mortality rate.

The causes of acute pancreatitis are not clear but known predisposing factors are gallstones and alcoholism. Other associated conditions include:

•

cancer of the ampulla or head of pancreas

•

viral infections, notably mumps

•

kidney and liver transplantation

•

hyperparathyroidism

•

severe hypothermia

•

drugs, e.g. corticosteroids, some cytotoxic agents.

Chronic pancreatitis

This is either due to repeated attacks of acute pancreatitis or may arise gradually without evidence of pancreatic disease. It is more common in men and is frequently associated with fibrosis and distortion of the main pancreatic duct. There is intestinal malabsorption when pancreatic secretions are reduced and diabetes mellitus (

p. 227

) occurs when severe damage affects the β-islet cells (see

Ch. 9

).