Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (155 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Chronic cholecystitis

The onset is usually insidious, sometimes following repeated acute attacks. Gallstones are invariably present and there may be accompanying biliary colic. Pain is due to the spasmodic contraction of muscle, causing ischaemia when the gall bladder is packed with gallstones. There is usually secondary infection with suppuration. Ulceration of the tissues between the gall bladder and the duodenum or colon may occur with fistula formation and, later, fibrous adhesions.

Cholangitis

This is inflammation of bile ducts in which there is partial or complete obstruction by gallstones. Complete obstruction of the common bile duct causes acute cholangitis, which is typically accompanied by biliary colic, fever and jaundice (because the flow of bile into the duodenum is blocked). In practice, not all of these symptoms are usually present. This situation predisposes to secondary infection which can spread upwards in the biliary tree to the liver (

ascending cholangitis

) causing liver abscesses.

Tumours of the biliary tract

Benign tumours are rare.

Malignant tumours

These are relatively rare and gallstones are nearly always present. Local spread to the liver, the pancreas and other adjacent organs is common. Lymph and blood spread lead to widespread metastases. The tumour has often spread by the time of diagnosis and, therefore, the prognosis is poor.

Jaundice

This is not a disease in itself, but yellowing of the skin and mucous membrane is a sign of abnormal bilirubin metabolism and excretion. Bilirubin, produced from the breakdown of haemoglobin, is normally conjugated in the liver and excreted in the bile (

Fig. 12.37

). Conjugation, the process of adding certain groups to the bilirubin molecule, makes it water-soluble and greatly enhances its removal from the blood, an essential step in excretion.

Unconjugated bilirubin, which is fat-soluble, has a toxic effect on brain cells. However, it is unable to cross the blood–brain barrier until the plasma level rises above 340 μmol/l, but when it does it may cause neurological damage, seizures (fits) and mental impairment. Serum bilirubin may rise to 40 to 50 μmol/l before the yellow coloration of jaundice is evident in the skin and conjunctiva (normal 3 to 13 μmol/l). Jaundice is often accompanied by

pruritus

(itching) caused by the irritating effects of bile salts on the skin.

Jaundice develops when there is an abnormality of bilirubin processing and the different types are considered below.

Types of jaundice

Whatever stage in bilirubin processing is affected, the end result is rising blood bilirubin levels.

Pre-hepatic jaundice

This is due to increased haemolysis of red blood cells (see

Fig. 12.37 and p. 59

) that results in production of excess bilirubin. Because the excess bilirubin is unconjugated it cannot be excreted in the urine, which therefore remains normal in colour.

Neonatal haemolytic jaundice

occurs in many babies, especially in those born prematurely where the normal high haemolysis is coupled with shortage of conjugating enzymes in the hepatocytes of the still immature liver.

Intra-hepatic jaundice

This is the result of damage to the liver itself by, e.g.:

•

viral hepatitis (

p. 324

)

•

toxic substances, such as drugs

•

amoebiasis (amoebic dysentery) (

p. 319

)

•

cirrhosis (

p. 325

).

Excess bilirubin accumulates in the liver. Because it is mainly in the conjugated form, it is water-soluble and excreted in the urine making it dark in colour.

Post-hepatic jaundice

Causes of obstruction to the flow of bile in the biliary tract include:

•

gallstones in the common bile duct

•

tumour of the head of the pancreas

•

fibrosis of the bile ducts, following cholangitis or injury by the passage of gallstones.

In this situation excess bilirubin is also conjugated and is therefore excreted in the urine. The effects of raised serum bilirubin include:

•

pruritus (itching)

•

pale faeces due to absence of stercobilin (

p. 296

)

•

dark urine due to the presence of increased amounts of bilirubin.

For a range of self-assessment exercises on the topcs in this chapter, visit

www.rossandwilson.com

.

CHAPTER 13

The urinary system

Kidneys

330

Organs associated with the kidneys

331

Gross structure of the kidney

331

Microscopic structure of the kidney

331

Functions of the kidney

334

Ureters

338

Structure

339

Function

339

Urinary bladder

339

Organs associated with the bladder

339

Structure

339

Urethra

340

Micturition

341

Diseases of the kidneys

343

Glomerulonephritis (GN)

343

Nephrotic syndrome

344

Diabetic nephropathy

345

Hypertension and the kidneys

345

Acute pyelonephritis

345

Reflux nephropathy

345

Renal failure

345

Renal calculi

347

Congenital abnormalities of the kidneys

347

Tumours of the kidney

348

Diseases of the renal pelvis, ureters, bladder and urethra

348

Obstruction to the outflow of urine

348

Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

349

Tumours of the bladder

349

Urinary incontinence

349

ANIMATIONS

13.1

The urinary system

330

13.2

Gross structure of the kidney

331

13.3

Structure of the nephron

331

13.4

Filtration

334

13.5

Renal filtration

334

13.6

Reabsorption

335

13.7

Aldosterone regulation mechanism

335

13.8

Secretion

336

13.9

Urinary mechanism of pH control

338

13.10

Ureters

339

13.11

Bladder

339

13.12

Urethra

341

13.13

Renal stone

347

13.14

Hydroureter

347

13.15

Hydronephrosis

348

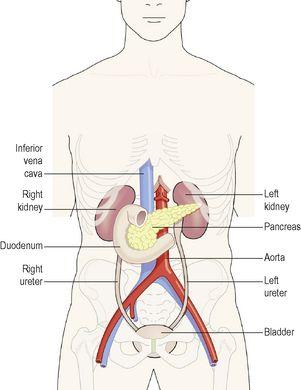

The urinary system is the main excretory system and consists of the following structures:

•

2

kidneys

, which secrete urine

•

2

ureters

, which convey the urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder

•

the

urinary bladder

where urine collects and is temporarily stored

•

the

urethra

through which the urine passes from the urinary bladder to the exterior.

Figure 13.1

shows an overview of the urinary system.