Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (4 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

compare and contrast negative and positive feedback control mechanisms

outline the potential consequences of homeostatic imbalance.

The

external environment

surrounds the body and is the source of oxygen and nutrients required by all body cells. Waste products of cellular activity are eventually excreted into the external environment. The skin provides a barrier between the dry external environment (the atmosphere) and the aqueous (water-based) environment of most body cells.

The

internal environment

is the water-based medium in which body cells exist. Cells are bathed in fluid called

interstitial

or

tissue fluid

. Oxygen and other substances they require must travel from the internal transport systems through the interstitial fluid to reach them. Similarly, cellular waste products must move through the interstitial fluid and transport systems to the excretory organs to be excreted.

Each cell is enclosed by its

plasma membrane

, which provides a potential barrier to substances entering or leaving. The structure of membranes (

p. 28

) confers certain properties, in particular

selective permeability

or

semipermeability

. This controls the movement of molecules into and out of the cell, and allows the cell to regulate its internal composition (

Fig. 1.3

). Smaller particles can usually pass through the membrane, some much more readily than others, and therefore the chemical composition of the fluid inside is different from that outside the cell.

Figure 1.3

Diagram of a cell with a semipermeable membrane.

Homeostasis

The composition of the internal environment is tightly controlled, and this fairly constant state is called

homeostasis

. Literally, this term means ‘unchanging’, but in practice it describes a dynamic, ever-changing situation kept within narrow limits. When this balance is threatened or lost, there is a serious risk to the well-being of the individual.

Box 1.1

lists some important physiological variables maintained within narrow limits by homeostatic control mechanisms.

Box 1.1

Examples of physiological variables

Core temperature

Water and electrolyte concentrations

pH (acidity or alkalinity) of body fluids

Blood glucose levels

Blood and tissue oxygen and carbon dioxide levels

Blood pressure

Homeostasis is maintained by control systems that detect and respond to changes in the internal environment. A control system (

Fig. 1.4

) has three basic components: detector, control centre and effector. The

control centre

determines the limits within which the variable factor should be maintained. It receives an input from the

detector

, or sensor, and integrates the incoming information. When the incoming signal indicates that an adjustment is needed, the control centre responds and its output to the

effector

is changed. This is a dynamic process that allows constant readjustment of many physiological variables.

Figure 1.4

Example of a negative feedback mechanism:

control of room temperature by a domestic boiler.

Negative feedback mechanisms

In systems controlled by negative feedback, the effector response decreases or negates the effect of the original stimulus, maintaining or restoring homeostasis (thus the term negative feedback). Control of body temperature is similar to the non-physiological example of a domestic central heating system. The thermostat (temperature detector) is sensitive to changes in room temperature (variable factor). The thermostat is connected to the boiler control unit (control centre), which controls the boiler (effector). The thermostat constantly compares the information from the detector with the preset temperature and, when necessary, adjustments are made to alter the room temperature. When the thermostat detects the room temperature is low, it switches the boiler on. The result is output of heat by the boiler, warming the room. When the preset temperature is reached, the system is reversed. The thermostat detects the higher room temperature and turns the boiler off. Heat production from the boiler stops and the room slowly cools as heat is lost. This series of events is a negative feedback mechanism and it enables continuous self-regulation, or control, of a variable factor within a narrow range.

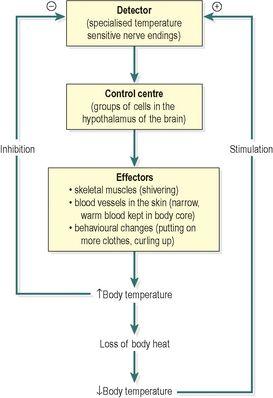

Body temperature is a physiological variable controlled by negative feedback (

Fig. 1.5

), which prevents problems due to it becoming too high or too low. When body temperature falls below the preset level, this is detected by specialised temperature sensitive nerve endings in the hypothalamus of the brain, which form the control centre. This centre then activates mechanisms that raise body temperature (effectors). These include:

•

stimulation of skeletal muscles causing shivering

•

narrowing of the blood vessels in the skin reducing the blood flow to, and heat loss from, the peripheries

•

behavioural changes, e.g. we put on more clothes or curl up.

Figure 1.5

Example of a physiological negative feedback mechanism:

control of body temperature.

When body temperature rises within the normal range again, the temperature sensitive nerve endings are no longer stimulated, and their signals to the hypothalamus stop. Therefore, shivering stops and blood flow to the peripheries returns to normal.

Most of the homeostatic controls in the body use negative feedback mechanisms to prevent sudden and serious changes in the internal environment. Many more of these are explained in the following chapters.

Positive feedback mechanisms