Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (8 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Figure 1.15

Coloured scanning electron micrograph of the skin.

The

epidermis

lies superficially and is composed of several layers of cells that grow towards the surface from its deepest layer. The surface layer consists of dead cells that are constantly being rubbed off and replaced from below. The epidermis constitutes the barrier between the moist internal environment and the dry atmosphere of the external environment.

The

dermis

contains tiny sweat glands that have little canals or ducts, leading to the surface. Hairs grow from follicles in the dermis. The dermis is rich in sensory nerve endings sensitive to pain, temperature and touch. It is a vast organ that constantly provides the central nervous system with sensory input from the body surfaces. The skin also plays an important role in regulation of body temperature.

Protection against infection

The body has many means of self-protection from invaders, which confer resistance and/or immunity (

Ch. 15

). They are divided into two categories: specific and non-specific defence mechanisms.

Non-specific defence mechanisms

These are effective against any invaders. The protection provided by the skin is outlined above. In addition there are other protective features at body surfaces, e.g.

mucus

secreted by mucous membranes traps microbes and other foreign materials on its sticky surface. Some body fluids contain

antimicrobial substances

, e.g. gastric juice contains hydrochloric acid, which kills most ingested microbes. Following successful invasion other non-specific processes that counteract potentially harmful consequences may occur, including the inflammatory response.

Specific defence mechanisms

The body generates a specific (immune) response against any substance it identifies as foreign. Such substances are called

antigens

and include:

•

bacteria and other microbes

•

cancer cells or transplanted tissue cells

•

pollen from flowers and plants.

Following exposure to an antigen, lifelong immunity against further invasion by the same antigen often develops. Over a lifetime, an individual gradually builds up immunity to millions of antigens. Allergic reactions are abnormally powerful immune responses to an antigen that usually poses no threat to the body.

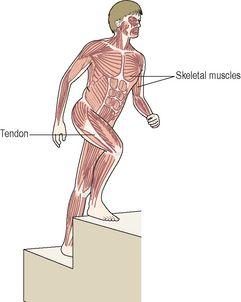

Movement

Movement of the whole body, or parts of it, is essential for many body activities, e.g. obtaining food, avoiding injury and reproduction.

Most body movement is under conscious (voluntary) control. Exceptions include protective movements that are carried out before the individual is aware of them, e.g. the reflex action of removing the finger from a very hot surface.

The musculoskeletal system includes the bones of the skeleton,

skeletal muscles

and

joints

. The skeleton provides the rigid body framework and movement takes place at joints between two or more bones. Skeletal muscles (

Fig. 1.16

), under the control of the voluntary nervous system, maintain posture and balance, and move the skeleton. A brief description of the skeleton is given in

Chapter 3

, and a more detailed account of bones, muscles and joints is presented in

Chapter 16

.

Figure 1.16

The skeletal muscles.

Survival of the species

Survival of a species is essential to prevent its extinction. This requires the transmission of inherited characteristics to a new generation by reproduction.

Transmission of inherited characteristics

Individuals with the most advantageous genetic make-up are most likely to survive, reproduce and pass their genes on to the next generation. This is the basis of natural selection, i.e. ‘survival of the fittest’.

Chapter 17

explores the transmission of inherited characteristics.

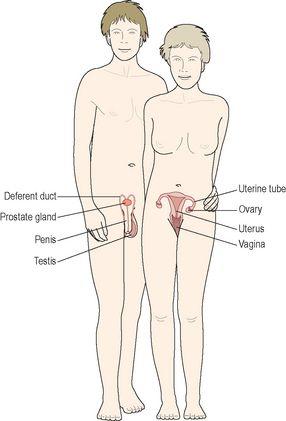

Reproduction (

Ch. 18

)

Successful reproduction is essential in order to ensure the continuation of a species and its genetic characteristics from one generation to the next. Fertilisation (

Fig. 1.17

) occurs when a female egg cell or

ovum

fuses with a male sperm cell or

spermatozoon

. Ova are produced by two

ovaries

situated in the female pelvis (

Fig. 1.18

). Usually only one ovum is released at a time and it travels towards the

uterus

in the

uterine tube

. Spermatozoa are produced in large numbers by the two

testes

, situated in the

scrotum

. From each testis, spermatozoa pass through the

deferent duct

(vas deferens) to the

urethra

. During sexual intercourse (coitus) the spermatozoa are deposited in the

vagina

.

Figure 1.17

Coloured scanning electron micrograph showing fertilisation (spermatozoon: orange, ovum: blue).

Figure 1.18

The reproductive systems:

male and female.

They then swim upwards through the uterus and fertilise the ovum in the uterine tube. The fertilised ovum (

zygote

) then passes into the uterus, embeds itself in the uterine wall and grows to maturity during pregnancy or

gestation

, in about 40 weeks.

When the ovum is not fertilised it is expelled from the uterus accompanied by menstrual bleeding, known as

menstruation

. In females, the

reproductive cycle

consists of phases associated with changes in hormone levels involving the endocrine system.

A cycle takes around 28 days and they take place continuously between

puberty

and the

menopause,

except during pregnancy. At

ovulation

(

Fig. 18.8

) an ovum is released from one of the ovaries mid-cycle. There is no such cycle in the male but hormones, similar to those of the female, are involved in the production and maturation of spermatozoa.

Introduction to the study of illness

Learning outcomes

After studying this section you should be able to:

list mechanisms that commonly cause disease

define the terms aetiology, pathogenesis and prognosis

name some common disease processes.