Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II (65 page)

Read Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Online

Authors: Keith Lowe

Stories like this demonstrate one of the major problems with getting to grips with what happened during the partisan war in the Baltic countries. It is plainly unthinkable that any partisan leader would make a habit of announcing his arrival to strangers by mail, or that he would risk such stunts purely for the sake of a meal – and yet such stories are recounted again and again as if they are true. The Lithuanian partisan Juozas Lukša recognized the importance of such mythology to inspire the people, but acknowledged that much of it was nonsense: ‘People sympathized with the partisans,’ he wrote in 1949; ‘therefore, tales of their heroic deeds were often exaggerated to the extent that only a skeleton of the truth remained.’

20

Given our present-day sympathy for all those who struggled against Soviet repression, it is easy to fall into the trap of hero worship. But however much we might like to imagine the partisans as Robin Hood figures, the majority of them did not fit this romantic image at all. Most joined the resistance not out of bravery but to avoid arrest, or deportation or being drafted into the Red Army. And they only remained in the forests while the benefits outweighed the risks: the vast majority of partisans returned to civilian life within two years.

21

While most partisans chose to resist out of a sense of nationalism, there were many who hid from the Soviets merely because they had collaborated with the Germans in one way or another, and wanted to avoid punishment. Some had been heavily involved in anti-Semitic pogroms and massacres during the war. The Ukrainian partisan movement in particular was founded on a violently racist ideology – but in the Baltic States, too, there was a dark history to some partisan units. The ‘Iron Wolf’ regiment in Lithuania, for example, had started out as a fascist organization during the war. While the racist basis of the group had declined substantially by the summer of 1945, there were still anti-Semitic elements to the stories they told.

22

It is perhaps unsurprising that some figures in the West were suspicious of their motives. In Britain, for example, the Archbishop of Canterbury made a speech suggesting that the Baltic partisans were fascists whose deportation was justified. While his comments were certainly misguided, they contained enough truth for some of the mud to stick.

23

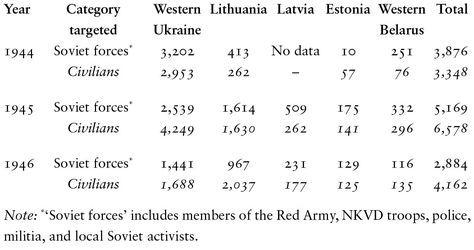

Even more problematic for the partisans was the Soviet assertion that they were not freedom fighters, but mere ‘bandits’. It was easy to refute such claims while they were engaging in pitched battles against Soviet army units – but it was much more difficult once they were obliged to direct their efforts against civilian targets. As I have shown, the partisans in Lithuania suffered such heavy losses in the early days that they were forced to change their tactics. From the summer of 1945 onwards, the vast majority of people they killed were civilians – mostly Communist officials and those who collaborated openly with the Soviets. The same pattern occurred in western Ukraine – and in Latvia and Estonia, where the resistance was never strong enough to openly challenge Soviet forces, civilian collaborators were the main target from the very beginning. Innocent people inevitably got killed, and goodwill towards the partisans began to drain away.

Table 3: Total deaths inflicted by the partisans, 1944—6

24

The partisans were therefore forced to walk a fine line. In order to succeed they had to portray themselves as an alternative authority to the new government, capable of enforcing their own will upon the people. And yet this had to be done without alienating those people. On the one hand they were obliged to punish anyone who collaborated too enthusiastically with the Soviets, but on the other hand they had to acknowledge that many of these local officials did not have any choice but to collaborate. In areas where they were strong they were able, for a time at least, to impose their own form of law and order on the countryside. In areas where they were weak, however, their only course lay in disrupting law and order. Amongst a population that was tired out from years of chaos and bloodshed, it became increasingly difficult to maintain support.

Like their Soviet counterparts, the partisans sometimes resorted to terror in order to impose their will. Sometimes this terror was simply the result of anger, frustration, or the heat of battle. In the Estonian town of Osula, for example, in March 1946, partisans launched an attack on the local ‘destruction battalion’, or Estonian volunteer militia. The attack was partly an attempt by the resistance to stamp their authority on the local area, but also an act of revenge for certain militia atrocities. Partisan leaders drew up a list of guilty officials and imprisoned them in the local pharmacy pending execution. According to the testimony of witnesses, the partisan operation soon degenerated into something of a frenzy:

The Forest Brothers set about killing the others according to their list. Soon they realized that the list didn’t include all the ones they wanted. Some of the men had gotten crazed with killing, and they started shooting women and children who were not on the list. The entire families of some authorities who had caused exceptional suffering to a few Forest Brothers were wiped out. For a while, the women succeeded in stopping the bloodshed. In one instance, they drove the partisans away from the wife of the destruction battalion commander, saying that a pregnant woman should not be killed.

25

A total of thirteen people are reputed to have been executed that day before the partisans dispersed and headed back into hiding.

On other occasions there were colder, more political reasons for terrorizing individual communities. For example, in an apparent attempt to bring a halt to the Soviet land reforms, partisans in Lithuania occasionally attacked peasants who had been granted land confiscated from larger estates. According to Soviet reports from Alytus province, some thirty-one families were attacked by partisans in August 1945 for this reason, and forty-eight people killed:

Among the killed were 11 persons from 60 to 70 years old, 7 children from 7 to 14 years old and 6 girls from 17 to 20 years old. All victims were poor farmers who had received land [confiscated] from kulaksNone of the killed worked for party or other administrative agencies.

26

In later years, when farms were being forcibly collectivized, the partisans resorted to burning crops, destroying the communal farm machinery and killing livestock. However, since these collective farms were still expected to provide their quotas for government warehouses, the only people to suffer were often the farmers themselves. In order to gather supplies during this time the partisans often had no choice but to break into communal stores. Since these stores now belonged to the community as a whole, it was the community as a whole that suffered. According to some historians, as the years went by the actions of the partisans began to look less like resistance and more like social obstructionism.

27

Many people also began to question what the continued violence and chaos was supposed to achieve. It had become increasingly obvious that the partisans were fighting a lost cause, and most civilians simply wanted the violence to stop. Forced reluctantly into taking sides, many now sacrificed their nationalist ideals for the sake of stability. Informing on resistance groups became much more common towards the end of the 1940s, not only by paid informers and former partisans who had been coerced into changing sides, but by ordinary members of the public. By 1948, the majority of arrests and killings of partisans – more than seven out of ten – came as a result of intelligence. In other words, they were betrayed.

28

One of the greatest mistakes of the Baltic partisans was to imagine that the war they were fighting was predominantly a military one. In reality they were being attacked on several fronts at once – not only militarily, but also economically, socially and politically. The Soviets understood from the outset how much the guerrillas relied on their local, rural communities for support. They therefore set about dismantling these communities with a ruthlessness that left the fighters reeling.

The first blow came in the immediate aftermath of the war, when the Communists embarked on the same programme of land reform that they were practising elsewhere in Europe. This was an issue that genuinely divided the population, with the poor and the landless naturally much more in favour of it than those who would be forced to give up parts of their property. Middle-class farmers were much more likely to join the partisans than the poorer peasants – this created an embryo of a class struggle, and allowed the authorities to portray the partisans as reactionaries.

29

This might seem like a subtle point, but it was an important political victory for the Communists, who could claim that they were the champions of the poor. Combined with other political scoops, such as the award of Vilnius to Lithuania – a city that they had always claimed, but never controlled – it meant that not everyone was quite so willing to support the partisans as some nationalists in the Baltic States would have it.

The second blow came in the late 1940s, when the Soviets once again resorted to the policy of deportation of their political enemies. Between 22 and 27 May 1948, over 40,000 people were deported from Lithuania; the following March a further 29,000 joined them.

30

In Latvia, the deportation of 43,000 people to Siberia effectively ended the hopes of the resistance.

31

While in the short term these events swelled the numbers of people willing to flee to the forest and join the partisans, it destroyed their support networks amongst the general population. From this point on, the partisans could no longer rely on their communities to provide them with food and other supplies. Instead they were forced to go out and requisition what they needed, thereby alerting the authorities to their presence.