Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld (19 page)

Read Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld Online

Authors: Linda Washington

BOOK: Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld

7.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Kings and Barons and Witches, Oh My

With Lancre being a principality, the king is where the buck stops. Verence II, the former fool, is the king of Lancre as of

Wyrd Sisters,

with Magrat as his queen in

Lords and Ladies.

Their word is law (unless some vampires happen to take over the castle, as in

Carpe Jugulum

). But the real power in Lancre, even with vampires around, belongs to the witches, especially to Granny Weatherwax (see

chapter 6

), the top witch in Lancre, a title her close friend and associate Nanny Ogg does not dispute. So any king worth his salt would get the witches on his side, as the second Verence does in

Wyrd Sisters.

(This is a lesson Duke Felmet fails.)

Wyrd Sisters,

with Magrat as his queen in

Lords and Ladies.

Their word is law (unless some vampires happen to take over the castle, as in

Carpe Jugulum

). But the real power in Lancre, even with vampires around, belongs to the witches, especially to Granny Weatherwax (see

chapter 6

), the top witch in Lancre, a title her close friend and associate Nanny Ogg does not dispute. So any king worth his salt would get the witches on his side, as the second Verence does in

Wyrd Sisters.

(This is a lesson Duke Felmet fails.)

The witches, like the wizards, adhere to the “a cat can look at a king” principle. While they may call him “Your Majesty,” they still do as they please, except when someone foolishly tries to lock them in a dungeon.

Granny is a textbook example of the Machiavellian principle concerning being feared rather than loved. Having a witch's hat is the key to power, as Granny reminds Tiffany Aching as well as any reader of any book Granny happens to be in.

According to

Lords and Ladies,

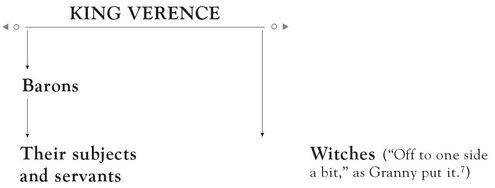

the chain of command in Lancre goes like this:

Lords and Ladies,

the chain of command in Lancre goes like this:

130

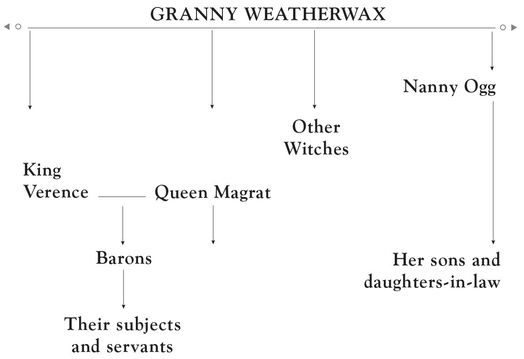

But we think the chain of command goes like this even if witches claim not to meddle:

But we think the chain of command goes like this even if witches claim not to meddle:

In Tiffany's farming community, the Chalk, the baron is supposedly top man under the king. But the real power belongs to Granny Aching, which still continues after her death. Even the baron seeks

Granny Aching for wisdom. Now that's power. And Tiffany is able to access that powerâthe power of the landâin

The Wee Free Men.

With Tiffany as the only witch around, she assumes the reins of authority, upon Granny's death.

Granny Aching for wisdom. Now that's power. And Tiffany is able to access that powerâthe power of the landâin

The Wee Free Men.

With Tiffany as the only witch around, she assumes the reins of authority, upon Granny's death.

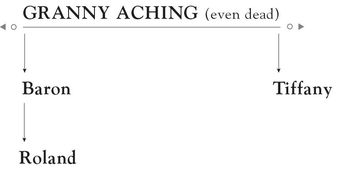

So in

The Wee Free Men,

the chain of command is something like this:

The Wee Free Men,

the chain of command is something like this:

In

Wintersmith,

we learn that in the baron's home, Roland's aunts (Danuta and Araminta) rule with an iron fist while the baron is ill, thus adhering to the curtailing of freedom principle in

The Prince.

They are not successful at cowing Roland, who is a reader of books by tactical titan General Tacticus and knows all of the secret passages in his home. Again, we'll have to wait and see how Roland shapes up as a leader. Thanks to his hero training, courtesy of the Feegles, we think he'll do just fine.

Wintersmith,

we learn that in the baron's home, Roland's aunts (Danuta and Araminta) rule with an iron fist while the baron is ill, thus adhering to the curtailing of freedom principle in

The Prince.

They are not successful at cowing Roland, who is a reader of books by tactical titan General Tacticus and knows all of the secret passages in his home. Again, we'll have to wait and see how Roland shapes up as a leader. Thanks to his hero training, courtesy of the Feegles, we think he'll do just fine.

Those who unexpectedly become princes are men of so much ability that they know they have to be prepared at once to hold that which fortune has thrown into their laps, and that those foundations, which others have laid before they became princes, they must lay afterwards.

âFrom

The Prince

, chapter VII, “Concerning New Principalities Which Are Acquired Either by the Arms of Others or by Good Fortune”

The Prince

, chapter VII, “Concerning New Principalities Which Are Acquired Either by the Arms of Others or by Good Fortune”

Uberwald is

the

place for politickin' and power-grabbin', as Pratchett reveals in

The Fifth Elephant.

Different factionsâvampires, werewolves, and dwarfsâscramble up the totem pole of power. In Shmaltzberg, the newly crowned Low King, Rhys Rhysson, exudes more political savvy than a popular favorite, Albrecht Albrechtson (an allusion to Alberich in the Ring Cycleâsee the end of

chapter 5

). Judging by the way he (and that pronoun is debatable by the end of the book) handles Dee and Albrechtson, he embodies to a degree the principle from

The Prince

's chapter VII quoted earlier, even though his election to the throne is not unexpected.

the

place for politickin' and power-grabbin', as Pratchett reveals in

The Fifth Elephant.

Different factionsâvampires, werewolves, and dwarfsâscramble up the totem pole of power. In Shmaltzberg, the newly crowned Low King, Rhys Rhysson, exudes more political savvy than a popular favorite, Albrecht Albrechtson (an allusion to Alberich in the Ring Cycleâsee the end of

chapter 5

). Judging by the way he (and that pronoun is debatable by the end of the book) handles Dee and Albrechtson, he embodies to a degree the principle from

The Prince

's chapter VII quoted earlier, even though his election to the throne is not unexpected.

The first task the Low King takes to establish a good foundation is to establish the authenticity of the Scone of Stone, the scone upon which all Low Kings sit when crowned. Although the scone was made in Ankh-Morpork, Rhysson manipulates his political rival into authenticating the scone. A good move.

The true queen of Machiavellian principles in Uberwald is Lady Margolotta, the vampire who is the Dragon King and Vetinari's equal in political genius. As she explains to Vimes, “Politics is more interesting than blood.”

131

Her shenanigans are like chess moves in a way, as she moves one piece here (Wolfgang) and another there (Vimes), but never puts herselfâthe queenâin check.

131

Her shenanigans are like chess moves in a way, as she moves one piece here (Wolfgang) and another there (Vimes), but never puts herselfâthe queenâin check.

When we first meet her in

The Fifth Elephant,

she's studying

Twurps' Peerage

âthe who's who of Ankh-Morporkâto find out who Vetinari might send as a delegate. This is the same chapter XIV

Prince

principle that Mr. Shine and the Dragon King's tactics show.

The Fifth Elephant,

she's studying

Twurps' Peerage

âthe who's who of Ankh-Morporkâto find out who Vetinari might send as a delegate. This is the same chapter XIV

Prince

principle that Mr. Shine and the Dragon King's tactics show.

The prince ⦠ought to make himself the head and defender of his powerful

neighbours

, and to weaken the more powerful

amongst them, taking care that no foreigner as powerful as himself shall, by any accident, get a footing there.

neighbours

, and to weaken the more powerful

amongst them, taking care that no foreigner as powerful as himself shall, by any accident, get a footing there.

âFrom

The Prince

,

chapter 3

, “Concerning Mixed Principalities”

The Prince

,

chapter 3

, “Concerning Mixed Principalities”

Â

Therefore, one who becomes a prince through the favour of the people ought to keep them friendly, and this he can easily do seeing they only ask not to be oppressed by him.

âFrom

The Prince

,

chapter 9

“Concerning a Civil Principality”

The Prince

,

chapter 9

“Concerning a Civil Principality”

In Djelibeybi in Klatch, a pharaohlike king rules in the manner of Egyptian pharoahs in our world. In

Pyramids,

Teppic (actually Pteppic) ascends to the throne after the death of his father. Before abdicating the throne in favor of his half-sister Ptraci, he even has a dream like the pharaoh of the Bibleâa dream of seven fat cows and seven thin ones (Genesis 41:17-24)âa dream that seems to come with the job of being the king. With the kingdom squarely between Ephebe and Tsort, Djelibeybi is in a perfect spot to influence the political arena of either country. But as Teppic learns, the first Machiavellian principle described in this section is firmly in place within the foreign policy of Djelibeybi. In short, keep each country happy and believing you support them, but keep them out of your land.

Pyramids,

Teppic (actually Pteppic) ascends to the throne after the death of his father. Before abdicating the throne in favor of his half-sister Ptraci, he even has a dream like the pharaoh of the Bibleâa dream of seven fat cows and seven thin ones (Genesis 41:17-24)âa dream that seems to come with the job of being the king. With the kingdom squarely between Ephebe and Tsort, Djelibeybi is in a perfect spot to influence the political arena of either country. But as Teppic learns, the first Machiavellian principle described in this section is firmly in place within the foreign policy of Djelibeybi. In short, keep each country happy and believing you support them, but keep them out of your land.

During his travels, Teppic learns about the Ephebian culture: that they have an elected Tyrant as a leader and are a democracy (or “mocracy” as Teppic describes it), rather than a monarchyâan idea he hopes does not catch on.

Both principles above can be seen in

Monstrous Regiment,

in Borogravia to be exact, a duchy like Luxembourg ruled by a duke and duchess or, rather, the Duchess who is believed dead. Borogravia is a country usually at war with its neighbors. During the war with Zlobenia, Vimes, as the duke of Ankh-Morpork, winds up in

Borogravia (sent by Vetinari) to “bring things to a âsatisfactory' conclusion”

132

after the Borogravians destroy several clacks towers. That's Ankh-Morpork's way of sticking its fingers in every political pie as well as demonstrating the first principle above (act supportive, but make sure no one gets into power that you can't control). If that means keeping out Prince Heinrich, the ruler of Zlobenia, well, so be it.

Monstrous Regiment,

in Borogravia to be exact, a duchy like Luxembourg ruled by a duke and duchess or, rather, the Duchess who is believed dead. Borogravia is a country usually at war with its neighbors. During the war with Zlobenia, Vimes, as the duke of Ankh-Morpork, winds up in

Borogravia (sent by Vetinari) to “bring things to a âsatisfactory' conclusion”

132

after the Borogravians destroy several clacks towers. That's Ankh-Morpork's way of sticking its fingers in every political pie as well as demonstrating the first principle above (act supportive, but make sure no one gets into power that you can't control). If that means keeping out Prince Heinrich, the ruler of Zlobenia, well, so be it.

Vimes's attempts to assess the political climate and end the hostilities involve curtailing Borogravia's “freedom” to continue the war with Zlobenia. But after meeting Polly Perks and her regiment, Vimes learns what Prince Heinrich fails to learn: to ask the people what they want.

According to Machiavelli, a principality is composed of two groups: the nobles and the people. A ruler who governs by the will of the nobles winds up alienating the people. A usurper attempting to take over an area would do well to avoid alienating the people. Prince Heinrich, take note.

To rise in the political sphere, it helps to be an assassin.

Vetinari and Teppic both trained as assassins. In Discworld, being an assassin is a profession for a gentleman, particularly an upwardly mobile gentleman. It certainly helps Teppic kill off a pyramid. And it usually helps one move up the wizard ladder.

Vetinari and Teppic both trained as assassins. In Discworld, being an assassin is a profession for a gentleman, particularly an upwardly mobile gentleman. It certainly helps Teppic kill off a pyramid. And it usually helps one move up the wizard ladder.

Â

The view is great from behind the scenes.

Carrot, like Lady Margolotta, knows how to act behind the scenes. Carrot gains Vimes's social standing (duke, commander) and has thus far eluded the grasp of those who would force him to ascend to the throne of

Ankh-Morpork. Lady Margolotta, as we've already mentioned, is adept at moving pawns.

Carrot, like Lady Margolotta, knows how to act behind the scenes. Carrot gains Vimes's social standing (duke, commander) and has thus far eluded the grasp of those who would force him to ascend to the throne of

Ankh-Morpork. Lady Margolotta, as we've already mentioned, is adept at moving pawns.

Â

Never count on werewolves to get ahead.

Dee tries to play the game of politics and loses badly, having been duped by werewolves. (Isn't that always the way?) Even Angua knows that werewolves cannot always be trusted.

Dee tries to play the game of politics and loses badly, having been duped by werewolves. (Isn't that always the way?) Even Angua knows that werewolves cannot always be trusted.

Â

Never cross

Vetinari

or

Mustrum Ridcully

.

They have a strange way of not dying. Ridcully, usually armed to the teeth even when going to bed, foils all would-be assassins. And Vetinari is almost immortal in the way that he refuses to die.

Vetinari

or

Mustrum Ridcully

.

They have a strange way of not dying. Ridcully, usually armed to the teeth even when going to bed, foils all would-be assassins. And Vetinari is almost immortal in the way that he refuses to die.

Â

Avoid scheming against your employer.

Mort, Death's one-time apprentice, tries by sparing the life of a princess and thus making “ripples in reality”

133

as everyone in Discworld winds up doing. Alas, that is not the way to get ahead in a job. He winds up dueling with Death. By the same token, Lupine Wonse, Vetinari's secretary in

Guards! Guards!

, is less than loyal to his boss when he schemes to depose Vetinari and put a stooge king on the throne. Wonse winds up DOA.

Mort, Death's one-time apprentice, tries by sparing the life of a princess and thus making “ripples in reality”

133

as everyone in Discworld winds up doing. Alas, that is not the way to get ahead in a job. He winds up dueling with Death. By the same token, Lupine Wonse, Vetinari's secretary in

Guards! Guards!

, is less than loyal to his boss when he schemes to depose Vetinari and put a stooge king on the throne. Wonse winds up DOA.

Albert, the wizard who would prefer to be immortal than die a wizard on earth, learns the true value of getting ahead: suck up to Death.

Â

Never borrow money from Chrysophrase or hire Cut-Me-Own-Throat Dibbler.

In fact, you're better off not talking to either of them.

In fact, you're better off not talking to either of them.

Why the Watch Works

A constable was empowered to apprehend

“all loose, idle and disorderly Persons whom he shall find disturbing the public Peace, or whom he shall have just

“all loose, idle and disorderly Persons whom he shall find disturbing the public Peace, or whom he shall have just

Cause to suspect of any evil Designs.”

âThe Metropolitan Police Act of 1829

134

134

If you've read the City Watch miniseries (

Guards! Guards!, Men at Arms, Feet of Clay, Jingo, The Fifth Element, Night Watch, Thud!

) within the Discworld series, maybe you consider the watchmen the few, the proud, but ultimately, the ineptâa far cry from the forensics experts of

CSI

(and its thousands of spin-offs) or other law enforcement agents in

Law and Order

(another show with multiple spin-offs). But that's not so far from reality, particularly in England and Australia in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries!

Guards! Guards!, Men at Arms, Feet of Clay, Jingo, The Fifth Element, Night Watch, Thud!

) within the Discworld series, maybe you consider the watchmen the few, the proud, but ultimately, the ineptâa far cry from the forensics experts of

CSI

(and its thousands of spin-offs) or other law enforcement agents in

Law and Order

(another show with multiple spin-offs). But that's not so far from reality, particularly in England and Australia in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries!

Before 1674, depending on where you wereâwithin the sprawling metropolis of London or the countryâyou would probably find the same amateur, unskilled form of peacekeeping taking place since the Middle Ages. But after 1674, the duty of keeping the peace fell

upon the shoulders of the justice of the peaceâthe magistrates. In country settings, this was probably the largest landowner in the area. Justices were part of a larger Commission of Peace body. But untrained constables did the legwork of keeping the peace. After all, there was no police force as such with rules in place. And the constables were men from the area who rotated the duty.

upon the shoulders of the justice of the peaceâthe magistrates. In country settings, this was probably the largest landowner in the area. Justices were part of a larger Commission of Peace body. But untrained constables did the legwork of keeping the peace. After all, there was no police force as such with rules in place. And the constables were men from the area who rotated the duty.

The justice of the peace had the authority to hold a trial and carry out a judgment. Depending on the offense, the sentenced person might be whipped, placed in the stocks, or fined. Needless to say, justice wasn't always served.

In London, justices weren't the wealthy landowners. They were the tradesmenâalso known as “trading justices”âwho received a fee every time a criminal was brought before them. So, some “administered justice,” as often as possibleâsometimes by inventing reasons to have people brought before them.

Also, in many of the parishes of London, watchmen were on patrol from 9:00 P.M. until sunrise. Some parishes also hired thief takersâbounty hunters like Stephanie Plum of Janet Evanovich's seriesâsome of whom were thieves themselves (unlike Stephanie Plum)! Before the passing of the Watch Acts, watchmen were selected from the homeowners in the area and served for a year. They could question individuals out on the streets at that hour (“Up to no good? Push off home, you!”), but couldn't do much about stopping crime. Also, they were part-timers. They rotated with men who, like them, had other employment. And there's something about not getting paid that puts a damper on one's enthusiasm.

Constables, during the daytime, had more authority to question and detain minor criminals. But, alas, they were few and could do little to deter major criminalsâlike those of the Carcer (

Night Watch

) variety.

Night Watch

) variety.

When Charles I allowed for watchmen to be hired, the low salary kept away more qualified applicants. Many watchmen were

poor or poorly chosen. Picture a frail, elderly man holding a stick and a lantern. There's something about the sight that doesn't ensure confidence in the justice system. Unfortunately, many also were corrupt (like Quirke or Sergeant Knock in

Night Watch

) and unskilled. (Bet you're thinking of Fred Colon and Nobby Nobbs right about now ⦠. )

poor or poorly chosen. Picture a frail, elderly man holding a stick and a lantern. There's something about the sight that doesn't ensure confidence in the justice system. Unfortunately, many also were corrupt (like Quirke or Sergeant Knock in

Night Watch

) and unskilled. (Bet you're thinking of Fred Colon and Nobby Nobbs right about now ⦠. )

So, two brothers (half brothers really)âHenry and John Fieldingâset out to set up a system of policing the city and its environs. Their dream began because Henry Fielding decided not to be the kind of trading justice he observed. Instead, thanks to his training as a journalist and a lawyer, he wanted to reform the office of magistrate and the laws concerning the poor. Having set up his magistrate's office at Bow Street, Henry also established a criminal law journal in the mid-eighteenth century. So, in a way, he was like William de Worde, the journalist in

The Truth

and

Monstrous Regiment.

Henry's journal later became known as the

Police Gazette.

The Truth

and

Monstrous Regiment.

Henry's journal later became known as the

Police Gazette.

The advent of the Bow Street Runnersâthief takers used by Henry and later John, who were rewarded due to the criminals they apprehendedâhelped in the later establishment of a regular police force. But during their lifetimes, the brothers could not get the government to agree on the necessity of having a regularly employed police force. John's plan for expanding the role of the Bow Street Runners was continually thwarted.

In the nineteenth century, the Watch Acts (particularly, the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829) were passed, allowing a tax to be levied to hire full-time watchmen. Sadly, it took the deaths of eleven people and the injury of five hundred (the Peterloo massacre of 1819), after an altercation between soldiers and unarmed civilians at a

protest rally, for the government to see the need for a better-trained peacekeeping unit. These were London's first police officersâa group which Sir Robert Peel, the home secretary at the time (the Vetinari of his day), helped set up. Richard Mayne and Charles Rowan, the first joint police commissioners in the formation of the police, are predecessors in a way of Commander Sam Vimes and Carrot Ironfoundersson. Ex-soldier Rowan (the Vimes), who was older than Mayne and had military training, was considered slightly more senior in rank. Mayne, like Carrot, had a strong sense of civic duty as well as knowledge of the law.

protest rally, for the government to see the need for a better-trained peacekeeping unit. These were London's first police officersâa group which Sir Robert Peel, the home secretary at the time (the Vetinari of his day), helped set up. Richard Mayne and Charles Rowan, the first joint police commissioners in the formation of the police, are predecessors in a way of Commander Sam Vimes and Carrot Ironfoundersson. Ex-soldier Rowan (the Vimes), who was older than Mayne and had military training, was considered slightly more senior in rank. Mayne, like Carrot, had a strong sense of civic duty as well as knowledge of the law.

No longer would these peacekeepers be called watchmen. They would be patrolmen. But they earned a nickname as wellâbobbies, after Sir Robert Peel. The first policeâa group of about three thousandâwore uniforms and patrolled like Ankh-Morpork's watchmen.

At the time this book is published, Vimes's counterpart in the Metropolitan Police Service is Sir Ian Blair, a man who rose in the ranks just like Vimes, from constable to commissioner.

In

Men at Arms,

Vimes is forced to bend with the times by hiring practices represented by significant segments of the population (e.g., a werewolf, a dwarf, a gnome, and a trollâmost of whom moved up the promotion ladder faster than Nobby). However, as you know, Vimes draws the line at hiring vampires until forced to do so in

Thud!

when Sally (Salacia Deloresista Amanita Trigestatra Zeldana Malifee ⦠von Humpedingâvampires have incredibly long names) comes on the scene.

Men at Arms,

Vimes is forced to bend with the times by hiring practices represented by significant segments of the population (e.g., a werewolf, a dwarf, a gnome, and a trollâmost of whom moved up the promotion ladder faster than Nobby). However, as you know, Vimes draws the line at hiring vampires until forced to do so in

Thud!

when Sally (Salacia Deloresista Amanita Trigestatra Zeldana Malifee ⦠von Humpedingâvampires have incredibly long names) comes on the scene.

The City Watch hiring practices mirror the Race Relations Act 1976 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 in Great Britain (acts of Parliament), as well as such U.S. laws as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its subsequent amendments and Title 42. Read for yourself:

British Law

Part II: Discrimination in the Employment Field

Discrimination by employers â¦

(1) It is unlawful for a person, in relation to employment by him at an establishment in Great Britain, to discriminate against anotherâ

(a) in the arrangements he makes for the purpose of determining who should be offered that employment; or

(b) in the terms on which he offers him that employment; or

(c) by refusing or deliberately omitting to offer him that employment.

Race Relations Act 1976, 1976 CHAPTER 74

135

135

Â

U. S. Law

SEC. 2000e-2. [Section 703]

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employerâ

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or applicants for employment in any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an employee, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Pub. L. 88-352) (Title VII)

136

136

In Britain, the Race Relations Acts were passed starting in 1965. But further revisions were needed, making necessary the Race Relations

Acts of 1968, 1976, and the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000. Third time's the charm, apparently.

Acts of 1968, 1976, and the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000. Third time's the charm, apparently.

Lately, however, with affirmative action under fire in the United States, reverse discrimination cases have had their day in court in some states, with demands for the end of quota-hiring systems, especially in regard to promotions on the force. It will be interesting to see whether the hiring quotas will come under fire in Discworld as well.

In the meantime, the Watch keeps on ticking.

Ripped from the Headlines?

I

f you watch the original Law and Order and its trillions of spin-offs, you know that their cases are “ripped from today's headlines.” In other words, they mirror many real-life cases.

f you watch the original Law and Order and its trillions of spin-offs, you know that their cases are “ripped from today's headlines.” In other words, they mirror many real-life cases.

While the news hasn't featured any golem or werewolf killings (at least to our knowledge), there have been real-life criminals who could have served as inspiration for the criminals the Watch tries to apprehend. For instance, such serial killers as Jack the Ripper, Ted Bundy, and John Wayne Gacy were the “bogeymen” who haunted police just as double-murderer Carcer has haunted the Watch.

Although there have been serial killers who killed more people, Jack the Ripper remains larger than life because he was never caught or identified, unlike Carcer. He (and police aren't entirely sure that only one person was involved) operated in Whitechapel in 1888, killing five prostitutes (possibly more; again, the police

aren't sure of the number) in a grisly way that gained him his nickname.

aren't sure of the number) in a grisly way that gained him his nickname.

These real-life killers helped spawn such twisted fictional serial killers as “Buffalo Bill” of The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris (the book; the 1991 movie screenplay was by Ted Tally).

Other books

The Jerusalem Creed: A Sean Wyatt Thriller by Ernest Dempsey

Hemingway Tradition by Kristen Butcher

Missing by Susan Lewis

Cooking Most Deadly by Joanne Pence

Bottleneck by Ed James

A Fairytale Christmas by Susan Meier

Fire at Dawn: The Firefighters of Darling Bay 2 by Ashe, Lila

The Lonely Ones by Kelsey Sutton

False Advertising by Dianne Blacklock