Ship Captain's Daughter (2 page)

Read Ship Captain's Daughter Online

Authors: Ann Michler Lewis

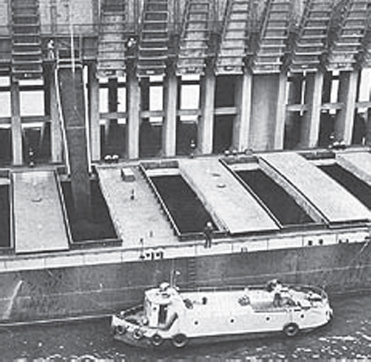

The Duluth, Missabe, and Iron Range (DMIR) dock, built in 1918, was the dock closest to our home. Ore for this dock was transported by train from the Iron Range's open pit mines sixty miles to the north.

For most of my early childhood, Dad was a first mate. Because the mate is in charge of loading the ship, it's hard for him to get off for more than an hour or two to come home for a visit. During those early years Mother and I spent a lot of time aboard ship visiting him. I stood with him out on deck. I watched as he cupped his hands around his mouth and shouted up at the dock boss on the train track high above us. He'd yell, “It's a two-car pocket,” or maybe he'd say three. I didn't know what that meant, but it sounded important. It was all very important, Dad said, because if he didn't get the cargo loaded evenly, the ship would roll. When he was loading, I couldn't really talk to him. I just stood beside him.

The big black spouts poured the ore from the train cars into the ship. Wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, they roared like angry lions as they dropped down from the dock into the hatches. When Dad gave the signal to open the chute, a few rocks bounced down, then a few clumps came, and then big rushes of rust-colored dirt flowed into the hatch. I'd take Dad's hand and lean over, looking down into the hold, watching as the pile grew higher and higher, thinking of what it would be like to fall in there. The loading started from the back and then skipped up to the front. The middle was loaded last to keep everything balanced. When all the hatches were half full, suddenly everything stopped. The whole operation came to a standstill, and the dockworkers took a break while the rest of the ballast (the water in the tanks that kept the empty ship steady) was pumped out. Before loading could be completed, all the ballast water had to be out of the tanks. That took about an hour. Now Dad could leave the deck.

Before going up to Dad's quarters, we always went into the mess hall for donuts and coffee, or leftover desserts, or sometimes

my favoriteâbologna and mustard sandwiches on toasted white bread. I loved the mess hall. There was always a lot of food to choose from, because the cook kept out what was called “night lunch”âeven if it was eaten in the daytimeâfor the men who missed meals due to their work schedules. The galley was warm and smelled like melted butter. Dockworkers and sailors stood around talking or sat on the stools at the long crew's table with their work gloves stuffed into their back pockets.

The off-watch crew waits to go ashore.

After our snack, we walked up forward to Dad's quarters. Mom was already there, knitting or reading. She'd put in her years on deck, so usually, after saying hello to everyone, she went up to Dad's room to wait for the break. Sometimes she took her sketch pad and drew pictures of the ships or the harbor. Sometimes she did Dad's laundry.

Dad's room had only two chairs. I sat on the bed, which was on a metal platform. Mother showed him the mail, had him sign some things, or talked about what was on the cover of the

Time

magazine she'd brought him. Maybe she gave him some photographs, or letters, or an article from the paper.

Mom knits in the captain's quarters on the SS

Charles M. Schwab.

Her knitting instructions are on the pillow.

While they talked, I pulled the heavy maroon bed curtains around me and pretended I was a movie star, or I fell asleep. After a while there was a loud whistle from the dock, Mother picked up her book or knitting, and Dad and I went back out on deck to finish the load and do the “trim”âthe final distribution of cargo.

Most visits were pretty much the same, but there is one I will never forget, thanks to the bumboat. Dad and I were out on deck. He was writing down figures in his black leather loading book, and I was passing the time by counting how many spouts there were in a ship's length, and then how many pigeons I could see.

Then (hooray!) I saw the bumboat scooting around the corner, bouncing over the water. It was like watching a cartoon character pull alongside. The little floating store was black with a yellow wheelhouse and a hemp bumper on the bow that looked like a mustache. Most intriguing was the mysterious door through which everyone disappeared.

Why was everyone so eager to go down there? I stood beside Dad watching as the men started to line up, slinging their legs over the railing, and scrambling straight down. Would I ever dare to do that? “No,” I said to myself, “I would not!” Just looking at the boat surging up and down on the waves made me dizzy. I watched with interest, however, as the men climbed back up with bags full of candy, magazines, clothes, cigarettes, and even an occasional transistor radio. Suddenly, I saw Mr. Kaner, the owner and captain, pop out the door. He had a mustache that looked just like the bumper on the bow of the boat, reminding me of Groucho Marx. Looking up, he waved, pointed to the door, and yelled, “Hi, Bill. Come on down.”

A bumboat at the Great Northern docks in Allouez outside of Superior, Wisconsin. The bumboats were floating convenience stores owned by the Kaner brothers of Superior. They are no longer in service due to the decrease in the number of ships on the Great Lakes and the ability to order from the internet.

I couldn't believe it when Dad turned to me and said, “Do you want to go?”

I gulped. “Well, um, maybe, kind of ⦔ I looked warily at the ladder. “You can do it,” Dad said. “I'll be right below you.” He slung his leg over the railing. Then he told me to turn around and bend backward under the wire as he guided my right foot down to the first rung. Then he drew down my left foot. Now my toes were resting right against the steel ship. There was no angle to this ladder, just straight up and down. It wiggled as I took my next step. I froze and sucked in my breath. Dad kept one hand on my leg.

“It's okay,” he said. “Keep going.”

I started again. When I felt my first foot on the deck, I started to breathe again. He took my hand, and we made our way to the little door. Four steps down and, pyew! The smell of sweet tobacco made me gag. I plugged my nose and hesitated, but the cheery calendar girls smiling and winking all around were very welcoming, not to mention the ladies on the covers of magazines on the book rack. Half of our ship's crew was in there, talking and laughing, drinking beer and smoking and telling jokes. No other girls in there, that's for sure!

Dad quickly steered me around to the back, which was so crowded that I disappeared in between the cases of watches, bins of underwear and socks, boxes of birthday cards, bottles of perfume, razors, aftershave, and columns of cartons of Camels and Lucky Strikes. All sizes of transistor radios covered the walls from floor to ceiling. I noticed a whole section of cough medicines and a display of Brylcreem with a big cardboard picture of a man with curly dark brown hair and a blond woman with her hand behind his ear. What I liked best of all, though, were the boxes of candy and gum lined up in double rows in front of the cash register right next to the cigarette lighters.

Behind the register stood Mr. Kaner, who was gruff, gravelly voiced, and kind of scary to a young customer like myself. He seemed to know everyone by name and was passing on the news from the last ship, where he had just seen a sailor who had previously been on our ship. When he saw me, his bushy eyebrows shot up in surprise. I took a step backward, but he came around the counter, bent down, and made a big fuss over me, telling me that I was beautiful and that I had been brave to come down. Afterward, he took me over to the freezer and let me pick out a free ice cream bar. Dad bought a Dreamsicle for himself, and we said good-bye to Mr. Kaner and went out on deck to eat our treats.

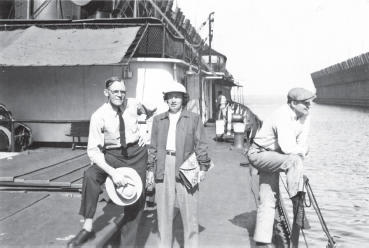

Standing in the stern of Dad's ship at the Great Northern ore docks in Superior, Wisconsin, Mom wonders where Dad and I have gone.

When we'd finished, we stuck our sticks in the big ash can with all the cigarette butts and went over to the ladder. We looked up andâuh-ohâsaw Mom glaring down at us. “I think we're in trouble,” Dad said.

It was a little easier going up. I didn't stop once, and I tried not to look scared, but after Dad helped push me under the wire again and then got himself back on deck, I heard my mother whisper to him, “Willis Carl Michler, what were you thinking! Don't you ever take that girl down there again!” Dad and I winked at each other.

I don't think the ladder was her main concern.

When the load was done, Mom and I hugged Dad good-bye and climbed down the ship's ladder, which was a little lower now with all the ore in the hold. The deckhands let go of the cables; the ship started backing out of the slip, and Dad sailed off for another five-and-a-half-day trip.

In the fall, my teacher taught a unit on Duluth, the harbor, and

the sailing life. She told the class that my dad was a sailor. She asked me if it was exciting to have a dad who worked on an ore freighter.

“It is when the bumboat comes,” I answered. I don't think she knew what I meant.

This life had many memorable moments, but they were totally unpredictable. For example, Dad occasionally carried a load of coal to Washburn, Wisconsin, seventy miles down the Wisconsin shore. Unloading coal took a long time, and didn't require much oversight by the first mate. Here, in a town with only one dock on a sandy beach, that could mean a walk in the lakefront park, a visit by ferry to Madeline Island, or, in the fall, a drive inland to visit an apple orchard. On one such layover my dad even triumphantly climbed the fire tower up on the hill of the neighboring town of Bayfield, as he'd once done as a teenage boy. These deviations from the routine were full of a sense of stolen time, of sheer luck. When such moments came along, we dropped everything and grabbed them.

One such window of opportunity came the summer I was eight. Dad was delivering cargo “down below” in Sandusky, Ohio, when the steelworkers went out on strike. Dad was marooned, his ship tied up for an indefinite amount of time. The strike could end at any time, but it seemed that the sides were deadlocked, and the ships wouldn't set sail again until matters were resolved. The question was, would the striking workers hold out long enough for Mom and me to drive all the way to Ohio? And if so, could Mom do it? She would either have to drive from Duluth to Chicago and then all the way around the bottom of Lake Michigan, or go through Wisconsin to Manitowoc, take the ferry across Lake Michigan to Ludington, Michigan, and then continue south to Sandusky.

A flurry of phone calls went back and forth. Mom looked at

the map one more time and then she decided, “We can do it!” The next morning we were off. She chose to go to Manitowoc. We packed our clothes, put sandwiches and coffee in our Scotch cooler, and started out. Sandusky, here we come!

We drove for hours, arriving at the ferry dock after dark. Men directed our car into the wide mouth of the car carrier, after which we climbed out and walked between the cars to the stairway up to the lounge. We found a bench to sit on, and I finally fell asleep. It was the middle of the night by the time we got offâtoo late to get our money's worth from staying in a motel, Mom saidâso we slept in the car for a few hours in the ferry parking lot. We started off again at first light, listening to Arthur Godfrey on the radio as we drove along. By midmorning, with only a few hours of sleep, Mom was starting to look really tired.

It was after lunch that we finally passed the “Welcome to Sandusky” sign, but we still had to find the shipyards. After stopping at a gas station to ask directions and making a few wrong turns, finally the guardhouse came into view. We pulled up and were just getting out to ask if we could call Dad on the phone, when the door of the little house opened and out he popped, in shorts instead of his usual work clothes. The trip turned out to be well worth it, as we stayed in Sandusky for two weeks.

Dad was still a first mate then and had only one room for quarters, but the captain let us stay in the guest rooms on board and even use the lounge, which had a little TV in a big blond wood cabinet. My mother thought that was very “modern.”

As the first mate, Dad was in charge of the crew, but there wasn't much to do while they waited for the strike to end except scrape and paint the deck and do other maintenance jobs. The men still served their watches but could leave the ship when they were off duty. Sometimes a group would walk together up to the little collection of gas stations and convenience stores out

on the road. Other times the men would talk and play cards with the crews of the other ships with which we were tied up. Dad's ship was one of four ships in a group, and we had to walk across the planks connecting them to go ashore. The good thing was that the pier where we were tied up was equipped with a stationary ramp to get on and off, rather than a ladder.

My parents and I onboard the ship in Sandusky as we wait for the strike to end

It was hot, and the crew was out on deck most of the time. We had an air conditioner in one porthole, but it was very noisy, so we were usually on deck, too. Dad got the men to tell stories. Oscar had been in the war and talked about the rain and mud in the trenches. He had a Norwegian accent and liked to shave outside. He had been a shoemaker in the war and fixed everyone's shoes now, including his own, by flipping the soles over when they began to wear out. Tony could draw cartoons, though mostly he drew figures of curvy women with short skirts, high boots, and long hair. Harry was from Tennessee and played the fiddle. He talked to my mother about his own mother. He was homesick.

During the strike in Sandusky, I take a turn sweeping on deck, while a couple of the deckhands, Tony and Harry, look on.

One day, for something to do, the men threw a firecracker at a seagull. The bird swooped after it and squawked hysterically when it blew up. They all laughed. I thought it was mean but I laughed too so that I wouldn't look like a sissy.