Ship Captain's Daughter (3 page)

Read Ship Captain's Daughter Online

Authors: Ann Michler Lewis

Most importantly, we had a car and could go off on excursions. That meant we could go to Catawba Island, which was magical. It had an amusement park that glittered at night and a beautiful beach where I learned how to swim. One afternoon, we were sitting on the beach on our blanket after eating our ship provisions of pork sandwiches and cupcakes, and suddenly Dad said, “Everyone in the water.” I loved the water, but I didn't know how to swim. We ran in hand in hand, Mom on one side and Dad on the

other, and kept running until I couldn't touch bottom anymore. They held me up as I began to float and then suddenly, Dad put his arm under my stomach and flipped my legs up parallel to the water and let me go.

“Paddle,” he shouted, and he moved his hands up and down dog-paddle style. I did, wildly, but my legs kept sinking down and down, and the water was coming up over my chin. As I was screaming and flailing, Dad rescued me, pulling my legs back up parallel to the water. Then he pushed me off again, yelling, “Kick

and

paddle.” I started paddling like mad, kicking at the same time, and suddenly I was swimming. We swam together all afternoon and then dried off in the late-afternoon sun.

The following year, 1953, started out the same. Dad left in mid-March when the lake thawed, and Mother started checking the paper again for his estimated weekly arrival times at ports near us. April went by, and May and June, and then, that July, it happenedâI was no longer the daughter of a first mate. Our whole world changed. Just before my ninth birthday, my dad became a captain.

The significance of this event is difficult to convey. Promotions were awarded strictly by seniority and the availability of ships. Ore contracts dictated how many ships were in service. The men on the officer's track took their various licensesâweather plotting, navigational aids, pilotingâand then they waited. The line of succession was long.

When my father first realized his dream of “getting a ship to sail,” thirty-six ships made up the Interlake Steamship fleet. As of this writing, there are nine.

It happened like this. Dad was returning to Duluth with a ship, and Mom learned that he was due to arrive at the Duluth, Mesabi, and Iron Range dock in Duluth at two a.m. She wouldn't let me go with her to meet the ship in the middle of the night, so my grandparents came and stayed over.

Late that night I heard Mom's alarm clock ring. Then I heard her lock the back door and start the car. I fell back asleep. The

next thing I heard was the refrigerator door open and close, and voices in the kitchen, and I realized Dad was able to get off the ship for a visit. They were home!

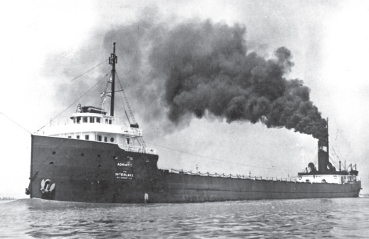

The SS

Adriatic

was Dad's first command and the ship my family remembered with enduring fondness.

JIM DAN HILL MARINE ARCHIVES, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-SUPERIOR

I got up and crept down the stairs, wanting to surprise them. But just when I came around the corner, I saw Dad pulling the cork out of a bottle of wine, and the two of them burst out laughing. I didn't know what to do, so I just stopped and listened.

“I couldn't believe it,” Dad said. “I heard that they might, and then I heard that they weren't going to, and then the skipper told me the news.” He sat down and started eating a cold leftover pork chop, and Mom toasted him with her glass.

I'd better go upstairs, I thought. But just as I was turning around, Dad looked up and saw me. “I thought I heard something over there. Come here, sleepyhead, and join the party.”

As I walked toward him, he jumped up to give me a hug, and then he surprised me by pushing me back at arm's length. Putting

his hands on my shoulders, he looked at me as if he meant business.

“Guess what, doll? They're pulling out another ship. They're moving more ore this summer than they have since the war, and they're fitting her out right now in Buffalo! And you know what?” He grinned. “Your dad is going to be the captain. After twenty-seven years on the deck, your dad is going to be âThe Old Man!'”

“Wow!” I said, as enthusiastically as I could.

Of course, I knew this was a big thing. I had heard the story about how, years before, Dad had narrowly escaped a loss in seniority when my grandmother was severely ill. He had asked for a leave, which was not granted. At that time it was unheard of even to ask. He did get off for a couple of weeks, and upon his return there was no job available. After pleading his case at the home office, he eventually got rehired. The five years of service he had accrued were saved. It was wartime, and it was finally decided that while he had been away, he was officially in the Merchant Marine. The service time was credited, and as a result my dad had the seniority required to be promoted without having to wait for the next opportunity.

I knew that, but Mom wanted to make sure I realized how important this was. She reached over and pulled me onto her lap, looked me in the eye, and said, “Do you really know what this means? It means that your dad will be up on his own deck, that he will have a bedroom, an office, and an observation room [a room the length of the front cabin ringed with portholes], and even a couch. It means he can get off when he is in port without asking and without trading watches. It means he will go to the meetings with the captains and chiefs. It means he will make more money. It means everything, that's what it means. It means we've been waiting for this our whole lives!”

“And,” Dad said to Mom, “it means that you now have thirty

sailing days. And guess what?” he said to me. “When you turn twelve, you can take trips, too.”

Dad standing proudly on the “captain's deck”

“It means,” he said, raising his glass to Mom, “that you are the wife of a ship captain! And that you,” he said, turning to me, “are the ship captain's daughter!”

Dad's first ship, the

Adriatic

, was half the length of the current fleet's flagship. It was coal-fired and old, but the captain's quarters

were constructed of beautiful wood. To our family, it was the

Queen Mary.

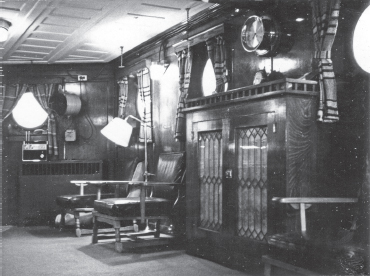

The captain's quarters of the SS

Adriatic

with its beautiful bookcase, and above it, the big brass ship's clock that chimed every half hour, day and night.

Many things did change after that night. But some things in the sailing life never do. It was true, Dad didn't have to load the ship anymore, which meant, if there was no pressing business, it was possible for him to be the first man off and the last one on in port. But even as a captain, there were the basic facts of the sailing life, and the main one was, there was no getting away from “sailing time.”

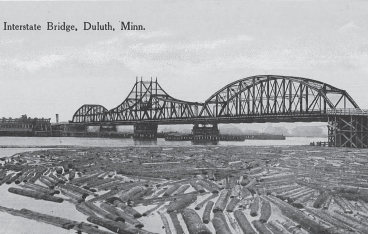

Now, Dad arranged for the dock boss to call when the ship was an hour or so away from being loaded. That was technically enough advance notice to make it back to the ship on time. But we lived in Duluth, and if the ship was docked at the Great Northern Ore docks across the bay in Superior, he'd have to cross the bridge. That was the “wild card,” as my mother said. The old Interstate Bridge opened for any passing ship.

The Old Interstate Bridge spanned the bay between Duluth and Superior. When it swung open for passing ships, it stopped traffic for an average of twenty minutes. It was replaced by the High Bridge in 1961, but a remnant of the old bridge remains as a fishing platform.

ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, KATHRYN A. MARTIN LIBRARY, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA-DULUTH

One night at the end of September, we got caught. Dad was home, and the dock boss called. We were just going out the door when Dad decided he'd better take his heavy wool mackinaw, as the weather could turn at any time now. He searched the front and back hall closets but couldn't find it. He went up to the attic to check the garment bags, but it wasn't there, either. Finally, it dawned on him; he had put it in the basement clothes locker under the stairs, the one with the mothballs in it. He ran down and grabbed it, shot outside, and headed for the car. But when he bent down to say good-bye to the dog, he noticed a screw missing in the gate latch and ran back in, got a screwdriver, and fixed it. By that time, we were running late.

Racing down Piedmont Avenue, we spotted troubleâa ship in the bay, headed for the bridge. It seemed like we could beat it, but by the time we got to Garfield Avenue, it wasn't looking good. Dad started gunning for the bridge, but just as we were about to

go over, the warning bells went offâ

ding, ding, ding

âand the big white arm came down. There we were, the first car behind the last car that made it.

Dad didn't swear in front of me very often, but this was one of the times that he did. Every minute's delay cost the company money, and the company was not forgiving. Watching the lights of the oncoming ship creeping toward the open span, the three of us sat in silence. In the glow of the lights of the dashboard, I could see my dad's cheek muscles clench and unclench. Mom even stopped talking.

After a few minutes, I looked out the back window andâwow!âthe whole sky was full of magical shifting shafts of light over the hills of Duluthâgreen, white, and pale yellow columns, bleeding and blending into each other, as when you turn a kaleidoscope.

“Hey, look,” I said, glad to break the silence.

“Holy Toledo!” Dad said. “I haven't seen an aurora borealis like that in ages.”

I asked him what caused it, and he started to tell me about gases, and sunspots, and solar winds, and electrical charges, the arctic sun, and the earth's magnetic field, and how sometimes he would see this from out on the water along the North Shore. He made me say “aurora borealis” over and over again, and then we all started saying it, and then the bells started ringing. The big arm in front of us lifted, and the bridge locked back into place. Dad put the car in gear, and we were off, leading the parade of cars making low whining noises on the metal span. As soon as we got to the Superior side, Dad turned left onto a side street to avoid the traffic lights and floored it. Mom's knees hit the glove compartment when he jammed on the brakes. He thought he'd spotted a police car up ahead, but it was just a taxi.

When we passed Barker's Island going about a hundred miles an hour, we could see the beginning of the dockâbut no

ship. “Uh-oh,” Dad said. “They must have shifted her back.” In another five minutes, we were at the turn in Allouez, in South Superior. When we roared up to the guardhouse, we could see that there were no spouts down. The ore train was moving toward us and the ship was at the end of the dock, loaded. We screeched to a stop. Dad jumped out of the car, flashed his pass at the guard, and started running, without looking back or even saying good-bye.

“Goodbye, Willie,” Mom muttered to herself.

We sat there for a minute, watching him. Then Mom slid over to the driver's seat, put the car in reverse, and turned around to back up. “Oh no!” she cried out. “He forgot his mackinaw!” She grabbed the coat and turned around, but he was gone. She slumped down in her seat. From the backseat, I could see a little tear run slowly down her cheek and land on her lip. She licked it, sucked in her breath, and then I watched as she rolled down the window and yelled at the top of her lungs, “I hate that bridge! And I hate steam boating!” The two of us drove home slowly.