Ship Captain's Daughter (8 page)

Read Ship Captain's Daughter Online

Authors: Ann Michler Lewis

From the pilothouse, Dad calls for a tug, with the radar situated to his left. In tense situations, I could see Dad's cheek muscles contract.

While he was calling, I slipped down the stairs, went into the bedroom, and plugged my rollers back in. As I was waiting for them to warm up, I could hear the ongoing background chatter of the shortwave radio upstairs. Then I heard my dad say, “Did Ann go down already?” I parted my hair to put a roller in my bangs, and when I looked in the mirror to stick the bobby pin in, for the first time I wondered: Did Dad ever secretly wish I were a boy? But I knew he wouldn't trade me.

Every year my dad was a captain, I took at least one trip with him, until I was nineteen. That year, I went to school in Paris to study French.

At first, it was exciting to be away, and I didn't even think about home. But by the end of the summer, I was homesick. I even started to miss the rhythmic drone of the foghorn and the cold, damp flannel-and-fleece Lake Superior “summer” days. It was the first time since I was twelve that I hadn't spent time aboard ship with my dad. Now I missed it, and I knew how much he must have missed me.

When a letter came from him, I couldn't wait to open it. I thought I knew what it would say: How long is it until you're coming back? The summer hasn't been the same without you.

What a surprise when I opened it and read: “Hi Honey, hope all is well. I'm having a great year so far. I've never had it so good. I have a crackerjack first mate, darned good second and third mates, the best cook in the fleet for a steward, a 2nd cook whom everyone wants, and the best chief I ever had. On top of that, I have a humdinger of a ship, which is a beautiful handler. It has a splendid master's quarters, and your mom was just aboard for a trip to Chicago where we got to see

Around the World in Eighty Days

, and it's been beautiful weather.”

He didn't say anything about me at all! He didn't even write

again for several months. The next time I heard from him was November, the meanest month of the shipping year with its steel grey skies, high winds, and waves that wash over the deck, gluing the hatches and the cables and the railings and the ladders together with ice.

During a late November day on Lake Superior, the ship rides low in the water from a heavy load and the weight of the ice.

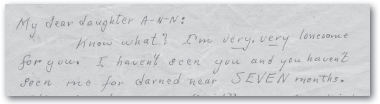

In Dad's letter to me in Paris, he calls me “A-N-N,” as he sometimes did. I had heard that he wanted to name me something a bit more glamorous, like Gloria, but Ann, which was my mother's middle name, won out.

This time, the letter began, “My Dear Daughter A-n-n: Know what? I'm very, very lonesome for you. I haven't seen you and you haven't seen me for darned near SEVEN months. We've been at anchor now for twenty-four hours in Lake Michigan. The wind has raised the water level in the lake six feet. We can't get into port, and I'm sitting here at my desk thinking I can't wait to see you for Christmas. Glad it's about over once again.”

It was a long November.

After I graduated from college, Dad arranged for me to take one last trip. I packed the usual: rain gear, books, stationery, and cards. We left Duluth at night. The red blinking lights of the TV and radio towers on the hills receded steadily as once more I left the city behind. Our destination was Toledo, Ohio. We were to get there in the daytime, which would allow us to get off and go “uptown.”

Dad said he knew where there was a great specialty popcorn store with caramel corn with lots of nuts, and he wanted to find a camera shop to take a look at the new Polaroid cameras. We talked a little more about what we might do: find a nice place for lunch, maybe even go to a movie. Then we looked out the front porthole at the deep darkness and went to bed. I pulled back the floral bedspread in the fancy passenger quarters, crawled under the quilt, and was just falling asleep when I could feel the ship start tossing up and down restlessly. I heard the plastic glass in the bathroom fall off the sink, roll across the floor, and hit the wall. The wind had shifted. Holding onto the end of the bed, then reaching for the chair to keep my balance, I opened the screen door and stole out to the bow to feel the cooling air. I looked downâso far down. The waves curled against us as we divided them with our bow, now lifting us up a few feet, then dropping us back down again before continuing their ride along the hull.

When they hit the back cabin, the lights on the stack blurred in the spray. Up, down, clouds hiding the moon, no lights of any ships around us, no sound except for the rhythmic boom and swish of the water. I was sailing again.

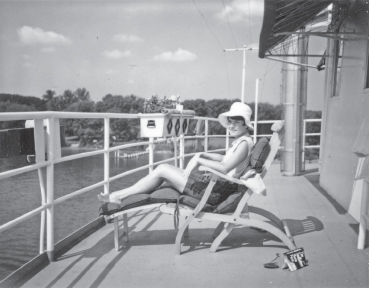

Dad waters his beloved pink-and-white petunias in our favorite spot on the “veranda.”

By morning the wind had died down and it was clear and sunny. Dad worked on payroll and I sat out on the deck and read. He joined me for a while, watered his flower boxes, and then called for the porter to bring up lunch. Before dinner that night, we walked around the after-cabin a few times for a little exercise, and then we went into the dining room for something I ate only aboard shipâcorned beef and cabbage.

Sailing on the SS

Herbert C. Jackson

through the St. Mary's River just below the Soo Locks

When the moon came up, we began to see the outlines in the distance of several ships starting to get in line to go through the river leading up to the Soo Locks. Standing out on the bow, Dad made me look for the North Star just to make sure I remembered how to find “true north.” Since ancient times, he said, Polaris has been the “sailor's star.” We now have modern navigational devices such as the gyrocompass, but those depend on human power sources that can fail. The North Star never goes out, he laughed. It's still a sailor's best friend.

He pointed out Cassiopeia, important because it's one of the constellations visible year-round in the northern sky. We stood there silently in a bowl of stars. The ship rocked gently in the night wind. “It's so awesome out here,” I said. “It feels like we're floating through time and space.”

“We are, Dolly,” he said, still gazing upward. “We are.”

We went up to the pilothouse together. When we nudged up to the breakwater, the deckhand called out the familiar “up against.” When we entered the lock, I held my breath as Dad expertly guided the ship to a gentle stop inches from the end of the lock. As we sailed down the St. Mary's River, we began reminiscing. We remembered the time I had made a bed in the equipment room off the observation lounge (living room), just for fun, and how I liked to help the men sweep the deck. The best was when it was so hot one trip that Dad rigged up a fire hose to spray me on the life raft.

The bells in the buoys chimed as we sailed past them. The houses ashore looked cozy with distant yard lights. After several hours, we reached the open water of Lake Huron and went to bed. From Dad's bedroom I could hear Debussy's “Clair de Lune” playing softly on his tape player. We both slept soundly until noon.

When we got to Toledo the following day, it was eight a.m., a lucky landing time for going ashore, though Dad had been up since four a.m. to take the ship in to the dock. Dad said that the guard here always let him borrow his car, so we were set for “going up the street,” as the sailors say. I was really looking forward to it.

When the unloading was under way (unloading took a lot longer than loadingâit was done with buckets called Huletts), we climbed down the ladder. Then we picked our way along the dock under the gyrating iron arms that were busily grabbing bites of iron ore from the hold and dumping them onto the towering stockpiles.

The dock boss was in the guardhouse. He and Dad clapped each other on the back and shook hands. The guard said he was happy to lend us his car. Dad thanked him and then inquired about his wife, Gladys, who was ill. Then the yard manager came in. Dad had known him for thirty years. He was credited with having put window boxes filled with petunias and geraniums on the retired locomotive that stood out by the maintenance shed

on a section of old track. Dad introduced me all around, and then, through the open door, we saw a man in a sport coat and tie approaching. He strode in and shook hands with Dad. They went outside and talked for a long time. Then they came back in. I thought Dad was finally ready to go, but instead of taking the car keys off the guard's desk, he just looked at me. I looked back at him expectantly. I didn't get it. I was anxious to get started on our time together.

To unload “down below,” a man went down into the hold, grabbing and lifting out cargo by operating the controls from a little compartment that he sat in just above the bucket.

“This is my daughter, Ann,” Dad said. “Ann, this is the fleet manager. He's here from the home office. He drove over from

Cleveland to take a look at the leaky seam that I reported last week. I thought we were going to check it out when we got back up above, that they were sending someone from Fraser Shipyard in Superior to inspect it then, but he said he decided to drive over and take a look at the situation firsthand when he heard we were coming to Toledo. We'll have to go back aboard. Maybe we can get going in an hour or so.”

I glared at the man. We went back aboard. Dad sprayed DDT on his office screen door, which was already covered with black flies, and then the two men sat in front of the fan on Dad's desk and talked about rivets and reviewed the problem. The leaky seam was in the first hatch. After a while, they went out on deck. I went into the guest room, where I was staying, closed the portholes and the door to keep out the noise, and started writing a letter. “Dear Mom, âHello' from Toledo, from the dock, that is. We were just about to leave the guardhouse to go uptown when a man from home office arrived. You know what that means!”

Aboard the SS

Herbert C. Jackson

, Dad and the fleet manager look down into the first hatch. The deck above them shows the windows of the lounge, available to us when the ship was not carrying passengers.

Two hours later, I heard Dad come back in. When I walked into the observation room, he looked at me and put his finger up to his lips. He stood still and listened for a minute, and then he turned up the volume on the weather channel, which was always on low in the background. He didn't like what he heard. He went back out on deck to look at the sky.

“Barometric pressure falling,” he said when he came back in, and he sat down and began mapping out a cell that was coming up the Ohio River Valley, commenting that it would probably hit us sometime before midnight. After a few minutes, his head slipped down on his chest. His cheeks relaxed, his hand loosened, and he dozed off, dropping the pencil onto the floor. I walked over and turned down the mechanical weather voice. Bad weather meant he would probably have to stay up most of the night.

I looked at him. He was still tall, thin, and handsome, but

wrinkles were beginning to form around his eyes and mouth. In his short-sleeved shirt, I could see that his tattoo was fading. The yellow in the snake's eyes had almost disappeared. I thought back to the night when Dad had become a captain, how excited he was. I wondered if he still felt that way. How many hundreds of nights had he stayed up? How many rivers had he navigated in fog? How many tense landings had he made? How many wild storms had he sailed through? How many family events had he missed? How many fleet managers had he dealt with? The older I got, the harder this life seemed. I wondered if the older man would choose the young man's dream again.

He woke up with a start and looked out the porthole at the thermometer, noting the ninety-degree temperature. Then he checked the humidityâninety percent. It clearly was going to be a “blister.” I could tell that his energy had dipped. It was too much to get off the ship again. I made a decision. “We don't have to go uptown, Dad. That caramel corn would just get stuck in our teeth anyway.”

He laughed and accused me of wanting to avoid going down the ladder again. I pretended that I was feeling tired and had gotten out of the notion.

It was the right call. He didn't argue. He swiveled around in his chair and reached up to his shelf of tapes and chose one to put on his new reel-to-reel tape recorderâRachmaninoff's Concerto no. 1, recorded by Van Cliburn. He said it reminded him of the sound of the wind, and the rhythm of the waves crashing on the deck. I wondered if it also reminded him of another vision he'd once had of himself. I knew that as a young boy he had taken piano lessons seriously and with promise. I had heard that at one time he wanted to be a pianist. What had happened to that dream? He still loved classical music, and all his ships had loudspeakers on the deck through which Bach and Beethoven occasionally wafted over the water. In the winter, he still

practiced his recital pieces, especially the octaves in the Turkish March, over and over again.