Ship Captain's Daughter (4 page)

Read Ship Captain's Daughter Online

Authors: Ann Michler Lewis

That night it sounded like there was someone or something in the houseâlike an animal rustling around. I crept into my parents' bedroom, but Mom wasn't there, and then I heard the hangers banging around in the bedroom closet. I was about to investigate, when a voice from the back of the closet called out, “Willie? Willie, is that you?” (Mom was the only one who called Dad Willie.) Just then the telephone rang, and Mom stumbled past me into the hall, reaching for the phone.

Uh-oh, I thought. Sleepwalking again. Sometimes she did that before Dad called. She seemed to have a sixth sense about when he would be in port. Tonight, however, he would still be in the middle of Lake Superior, which meant it would be a ship-to-shore call, which also meant it must be important.

“Yes, yes. I'll accept the charges,” she said.

They talked for quite a while, and then I heard her say, “Not

even time for a good-bye?” I didn't understand it when she said, “Ours is a winter affair,” but I giggled right out loud when, after a long silence, I heard her say, “Good-bye, sweet prince.” I thought she was awake, but she must have still been dreaming.

A few days later, a local reporter called Mom, saying she wanted to do a feature article for the

Duluth News Tribune

about the ship captains' wives. It wasn't good timing. Mother had a feeling that the reporter already knew what she wanted to write. People loved to romanticize this life, and Mother wasn't in the mood. But the reporter was a woman and said she was eager to tell it like it really was, so Mom met with her and did just that.

“At home alone, a skipper's wife, of necessity, becomes a jack-of-all-trades,” my mother told the reporter. “She not only has to learn to balance the checkbook, she becomes self-sufficient. She must learn to change a faucet's washer, do electrical repair work, clean the garage, and mow the lawn. A wife may accompany her captain husband on the lakes for up to a month of the season, but most of us break up the timeâit would be too confining to stay aboard ship for a month at a time.”

She went on to say that sometimes she was afraid of the weather. “Years ago a ship would head for the nearest port in a storm. Now, with modern technological advances, like radar to look ahead at the weather, the ship just keeps going. Those Lake Superior storms can be frightening.

“There could be a real morale booster,” Mom continued. “If only a captain could have a week or two at home during the summer to see Duluth without overshoes and storm coats in its summer fineryâwithout having to watch the clock for sailing time.”

But then ⦠“Night or day, it's always a thrill to go through the Soo Locks,” she conceded, adding that Burns Harbor was her favorite port. “It's such a clean, lovely place compared to most other stops.”

Sure enough, when the article appeared in the paper, the

reporter had summed up the interview with the headline, “Life of Skipper's Wife Rewarding.”

“Oh, no,” I thought; she'll say, “I told you so.” But included in the article was a picture of Mom and Dad in the pilothouse behind the wheel. They were smiling. I guess the picture must have brought back the good times, too, because she cut it out and put in on the refrigerator, where it stayed until it yellowed and faded. And surprisingly, she didn't say anything about the choice of title.

The portrait of my parents that ran with the article in the

Duluth News Tribune

The newspaper article in which Mother shared her thoughts about her life as the wife of a ship captain appeared in the

Duluth News Tribune.

DULUTH NEWS TRIBUNE

Finally the summer of my twelfth birthday arrived, and I was old enough for my first sailing trip. It was exciting at first, especially the fire drill, when all the horns and whistles were blowing, but it wasn't long until the days dragged on a bit. The wind, water, and sky seemed endless. Lake Superior was the best for Dad, as after he cleared the breakwater, barring bad weather, it was twenty-six hours of open lake to the Soo Locks. There were always paperwork and occasional personnel issues, but for the most part, it was the time when he had a little break, to sleep, and read, and listen to classical music, which was his passion. Dad loved having us on board with him and tried to make it interesting and fun, but he was also used to solitude. He was able to sit for long periods of time thinking, working on projects, and not talking. For a passenger like me, some days could be long, especially when it was my birthday and nobody seemed to notice!

The day I turned twelve, Mom appeared to be asleep in the bedroom. Dad was sitting at his desk mending a transistor box, and I was just standing there watching. Then, suddenly, the telephone above his desk rang and the red light started blinking. It was the chief engineer inviting us back to the engine room.

“OK, Harvey,” Dad said. “We'll be right back.”

Whoopee! I thought. Something to do! We got on our jackets and quietly slipped out the door. I held Dad's arm as we walked

back aft. Walking aft made me kind of dizzy, because the ship is moving forward while you're walking backward, so you're going backward and forward at the same time.

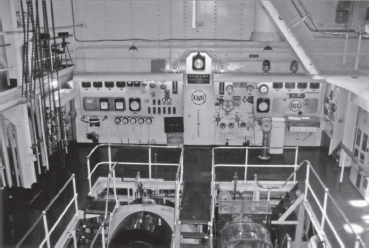

The engine room with all its gauges on the floating museum the SS

Irwin

moored in the Duluth harbor

When we got to the middle of the after-cabin, Dad pushed down the handle of the heavy steel door. We stepped over the high coaming and turned around to go backward down the steep steps. It was like entering the inner workings of an enormous watch. Everything was ticking and whirring. The big pistons were going up and down, lights were blinking, the little wheels in the gauges were spinning, and in the middle was the chief engineer, sitting at his desk, drinking from his coffee mug. With no windows, the engine room was warm and smelled of oil.

“Well, hello there, young lady,” the chief said. “You know, I had an idea.” He took us to his tool bench and showed us a pile of blocks of wood that he'd cut out. “I thought we could make some little boats,” he said. He took one piece of wood and nailed it on top of another larger piece, and then he nailed another little

piece on top of that, and it did look like a boat. Then he screwed an eye hook in its bow that he had sawed into a point, tied some twine to it, and superglued a toothpick with a little American flag on top.

My dad laughed and said, “Blow me down, Harvey.”

Then the chief looked at me and said, “Now you do it.”

I picked up the hammer and the nails that he'd laid out, took the other big block of wood and nailed a little smaller one on top of it, and a little smaller one on top of that, and he screwed an eye hook in the front of it and put the flag on top. He put a long piece of twine through the eye hook, and then we went over to the gangway. He pushed down with all his might on the big clamps and opened the top half of the gangway door, which opened onto the deep blue Lake Superior water. The ship was loaded so the water was just a couple of feet below us.

He tied the twine around my wrist and threw the boat in. It bounced around a bit before diving under the water. He reached for the string and pulled it in, letting it back out slowly, and when he handed the string to me again the boat was floating. Then he gave the first one that he'd made to Dad, who threw it in. It bounced around a bit, and then it floated, too. We laughed and sailed our boats in the sun.

Then the chief turned to me and said, “I hear we have a birthday girl with us today.” Dad winked, and I blushed. When we got back to our cabin, Mom had a birthday cake waiting with twelve candles. She and Mr. Gregory, the cook, had made it. I blew out the candles and made a wish for smooth seas and a daylight landing, so we could get off the ship and go shopping.

It wasn't long until I discovered that the most exciting place aboard ship by far was the pilothouse. It was like the forward end's family room. During the river passages, the captain and a mate and the wheelsman were always up there, and on the half hour,

after checking the spar and the running lights, the watchman came by with his standard report, “Lights are bright.” Watches were four hours long. Some men had been together for many seasons and had known each other on different ships over the years. At that time there were no crew rotations for vacations, so a group of men worked together for an entire sailing season and formed (for better or worse) a work family.

Nighttime was the best time in the pilothouse, when the radar and direction finder were lit, and the two-way radio jabbered with shipping traffic. The men talked about the news, their families, their childhoods, and sports, and everybody smoked, drank coffee, and ate donuts. Sometimes, when it was warm, the doors on either side were latched open, and everyone stopped talking as we sailed in the glow of the moon. All you could hear was the turning of the wheel and the lapping of the water on the bow. One night, Dad bet me I couldn't stay up all night, but I had to try. Right before sunrise, it was deadly quiet. The night loosened around the edges; the blackness thinned but it wasn't quite light. The smell was different, a little like fish, and now you could see that the leftover bacon sandwiches from two a.m. had gotten crusty on the windowsill and the fat had hardened. A wind came up, causing a little bounce to the ship. It started to feel humid, and the horizon line became visible, as straight as if it had been drawn with a ruler. It was morning. I had made it!

A few days later, when I'd read all the books I had brought aboard, all the magazines, and all the funnies in the papers from the Soo, I went up to the pilothouse to visit and picked up the

Merchant Marine Handbook

on the chart desk. Dad looked over at me, smiling, and asked how I liked it. I smiled back and said I liked it just fine. I quickly flipped the page I was on and impressed him when I asked some questions about cargo boom stresses and blank spots on the radar. Later, he told everyone at

dinner what a good little sailor I was and told me that I should get my A.B. (able-bodied seaman's license).

I never told him that the chapter I was reading was the one titled “Men's Health,” which included anatomically correct pictures and a fascinating section on rashes.

The perfect momentâcalm seas and the glow of the moon. The old-style telescoping hatches are visible. In bad weather they were covered with canvas tarps to prevent leakage.

As morning broke after a long night in the pilothouse, the horizon line looked as straight as if it had been drawn with a ruler.