Still Foolin' 'Em (18 page)

Authors: Billy Crystal

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

Meg Ryan had auditioned to play my girlfriend in

Throw Momma.

I’d thought she was great and a perfect compliment to me, but Danny DeVito had seen her as a tad young and cast Kim Greist. This time, when Meg came in to read with me, we all knew instantly that we were Harry and Sally. She was beautiful, she was adorable, she was really funny, and she had that awkward kind of grace that is found in only the best screen comediennes. I often wonder if Meg had gotten that part in

Throw Momma,

which I had done just before this, would Rob have cast her? Would he have thought,

I just saw this?

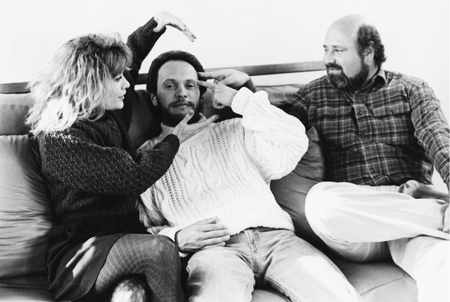

Once Meg was on board, Rob, his producing partner Andy Scheinman, Nora, and Meg and I would have lengthy meetings where we just talked about men and women and relationships and tried to come up with fresh dialogue and create new scenes. I think this process is what made the movie so personal, because what Harry and Sally went through was so real. When Nora brought up the issue of women faking orgasms during sex, Rob couldn’t believe it. “Well, they haven’t faked one with me,” he said. It was Meg’s idea to have a scene where Sally tells Harry about this and, like Rob, Harry can’t believe it, so she fakes one in a public place. I said, “Like a restaurant,” and then Rob said it should be a loud orgasm, with everyone watching her, and then I said, “When it’s done, an older woman says to a waiter, ‘I’ll have what she’s having.’” And that’s how it happened. In retrospect, it may be the longest orgasm in history.

Once the script was finished, we renamed it

When Harry Met Sally …

and the cast was completed with the excellent additions of Bruno Kirby and Carrie Fisher. We started filming in Los Angeles, then moved to Chicago and finally New York.

Rob was the perfect director for this movie, although sometimes he was too good of an audience. He would break out laughing and ruin takes, but in my heart I knew that if I had made him laugh, we were in the right zone. Early on, I had a very honest talk with him. This movie was so personal to him, I’d been starting to feel a little restricted. I didn’t want to play Rob; I wanted to be Harry. I told him that he needed to move out of Harry so I could move in. He totally understood and gave me more freedom with the role, as well as the best gift an actor can get from his director: trust.

One day we were shooting at the Temple of Dendur, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’d had this thought that when you start to get really comfortable with someone, you show them your funny “voice.” Usually it’s a silly-sounding character that you use in your “special moments.” You let your guard down and trust the person to listen without judgment, because you’re probably falling in love with them, and they with you. It became the “pepper pepper” scene, where Harry uses this crazy voice and gets Sally to repeat, “I would be proud to partake of your pecan pie.” It was all improvised. At one point—you can see it if you Google the scene—Meg actually looks off to where Rob is standing. Harry then asks her out, in his silly voice, and she tells him she has a date, and then Harry, his feelings kind of hurt, flirts with her by telling her to wear a skirt, that she looks really good in skirts. It’s one of my favorite moments in the movie, and it only happened because Rob was so open to trying ideas and Meg was so damned talented.

It doesn’t get any better.

(Photograph © Andrew Schwartz)

The night before shooting the orgasm scene in Katz’s Deli, Meg was nervous about it when we talked on the phone. After most of our shooting days, we spoke on the phone as Harry and Sally would, discussing what the day had been like and how we felt about the new one coming.

The orgasm scene was worrisome because she would have to have one thirty or forty times that day. Which would have tied my all-time junior high record. I was as reassuring as I could be, and frankly, being the one sitting across from her, I was looking forward to it.

The next morning, we met on the set and did a rough quiet rehearsal. She seemed nervous and wasn’t happy with her wardrobe, and she ended up wearing a sweater of mine. Once Barry Sonnenfeld, our outstanding director of photography, was done lighting, we walked onto the set, which now was filled with the “atmosphere.” (I don’t like the term “extras”—that means we ordered too many. “Background artists” is better yet.) Rob’s wonderful mother, Estelle, was sitting at a nearby table. She would be the “I’ll have what she’s having” lady. We started to rehearse, and Meg seemed tentative. First orgasm, so-so; next one like we’d been married for ten years. Perhaps she was nervous about sharing her orgasm with so many strangers. Rob, getting a bit impatient, then asked her to step aside for a moment so he could show her what he wanted. Now I’m sitting across from this large, sweaty, bearded man. It looked like I was on a date with Sebastian Cabot. He then had an orgasm that King Kong would have envied. He was screaming, “YES! YES! YES!” and banging the table so hard, pickles were flying and cole slaw was in the air. When he was done, the background artists applauded and Rob took me aside. “I made a mistake,” he confided. “I shouldn’t have done that.”

“Meg will be okay. I don’t think you embarrassed her,” I said.

“That’s not what I meant,” he said. “I just had an orgasm in front of my mother.”

Once we started shooting, Meg was spectacular. All day with the camera either on her or on me, she had sensational orgasms. My reactions to her became more fun to do as she came up with new little moans and groans. Months later, when Rob had finished his first cut of the picture, we had a test screening in Pasadena, California. The movie was playing really well, and then came the orgasm scene. The laughs were enormous, and when Estelle said her line, the place exploded. I was sitting in the back with Rob and we just grabbed each other’s arms. We knew we had something special.

* * *

After

When Harry Met Sally …

came out, Michael Fuchs asked me if I’d be willing to go to Moscow and do a stand-up special for HBO. Michael had created HBO and was always looking to expand television’s boundaries. If people were paying for TV, he felt, they should be getting something they couldn’t see on network television. It would be the first time an American comedian would perform in the Soviet Union. Gorbachev was in power, and the wall had not yet come down. I found the prospect daunting but intriguing, so I joined Michael and a small group of HBO executives that included Chris Albrecht, who was Michael’s right hand at the time and would become the programming genius behind

The Sopranos

and

Sex and the City,

and we made a trip to Leningrad and Moscow to get a feel for the country and its people and see if performing there was possible.

Leningrad—St. Petersburg now—is a beautiful city, with lovely bridges spanning the Neva River. We met with “humor officials,” who told us of their concerns about this proposed show. It was very similar to what I was used to, actually: Russia’s humor officials were the same dour comedy-development execs we have in the States. What was I planning on talking about? they asked. Could they see the script? We explained that we were just doing research at this point. We had a KGB man with us at all times, and probably a few others watching us.

While we were there, the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur arrived, and the Jews in the group who were feeling guilty that they weren’t home with their families, or just merely feeling guilty, wanted to go to synagogue. We found the only temple in the city still standing, which was moving in itself. Leningrad had once had twenty-four synagogues, but all the others had been destroyed over time, a stark reminder of what had happened to the Jews in the Soviet Union. Our group of ten or so men tried to go in, but we were refused entry by an elder of the temple because we didn’t have head coverings (yarmulkes). We explained that we were Americans whose roots were in Russia and asked, in the spirit of our ancestors, would the rabbi make an exception and let us in to say our Yom Kippur prayers? Again he refused us, pointing to our bare heads. We left angry and frustrated, but across the street we found an outdoor market, and somehow somebody was selling a black velvet painting of Elvis, which we bought for two dollars. With a Swiss Army knife we cut some circles out of it, and we put the new “Elvis yarmulkes” on our heads. We confronted the elder with our new yarmulkes, and reluctantly he let us in. Elvis had entered the building.

The aging interior of the temple was still beautiful, but it had that musty aroma of an old apartment. Though it was a large place where men traditionally sat downstairs and the women upstairs, only a handful of people were there. On this, the holiest of days, most synagogues in the United States are jammed, so we all felt the same sadness. If the pogroms and the anti-Semitic Stalinist regime hadn’t happened, this place would be full. There weren’t many Jews left in the city, and those who were still there were apparently reluctant to be seen going to synagogue. I imagined what it must have been like to be a Jew living here in my grandparents’ time—it seemed dreary and scary enough in 1989. As we boarded the train to Moscow, I still wasn’t convinced I could do the show. The train leaves at midnight, and when you wake up you are in Moscow.

Midnight Train to Moscow

sounded like a title to me; I thought,

Now if I only had a show to go with it

.

The people in Moscow were more open to us. The lines we’d heard about, of Russians waiting for goods, were everywhere. Around three each afternoon, when work was done, the longest lines were for the liquor stores—or as I called it, “Unhappy Hour.” Soon the streets were littered with tipsy Russians. One evening we had arranged a meeting with one of the Soviet Union’s top comedians at a restaurant overlooking Red Square. We were going to videotape our conversation and perhaps use it in the show. Sitting at our table, we watched the entrance to the restaurant, not knowing who we were looking for. Man after man entered and glanced around for a table, and I somehow knew that each one wasn’t “him.” Then a thirty-five-ish beleaguered-looking man walked in and paused. He slouched a little and had a tinge of anxiety in his eyes. “That’s him,” I said, and it was.

We greeted each other warmly and, through his translator, started talking shop. He and I had many things in common. He also didn’t sit down before a show and instead he paced in his dressing room; he ate at the same time I did before a performance. He said he made love to his wife the night before every big performance and asked if I did. I said I didn’t know his wife, but if he insisted, I would. I asked if he liked it when his family was in the audience, and he responded through his translator, “No, I am Jewish, too.” But a few nights later, when we went to see him perform in a large theater, he simply sat down and read a text of his comedy that had been approved by a committee! He wasn’t a stand-up; he was a sit-down comic. It was hard to fathom that his material had been censored.

One thing I did keep thinking about was my own Russian ancestry. My grandmothers were both from Russia, as was my dad’s father. What if I made the show about finding my roots? The idea started to percolate. It could be funny but also have a soul. With another family member’s help we found thirty or so distant cousins still living in Moscow. It was by chance—and choice—that some of my family remained in Russia while others flourished in America. Some saw that the revolution was coming and decided to flee, while others thought, “We will stay, it won’t be so bad, and we’ll come later.” They never did. Who would I have been if my grandmother didn’t get out at the age of fourteen? Probably a really funny tractor driver in Minsk.

When we returned to Los Angeles, I started to write the show with Paul Flaherty and Dick Blasucci. Our idea was to begin with a parody of

Field of Dreams,

with the voice that said, “If you build it, they will come” instead being the voice of my grandmother, urging me to go to Russia and find my roots. “If you go there, take a jacket,” the voice—Christopher Guest—whispered. For the stand-up portion of the special, I studied Soviet television to see what people were watching. Charlie Chaplin movies were being shown almost every day, and he was referred to as “the Little Jew.” Which, by coincidence, is the same thing they called him when he tried to join a country club in Hollywood.

I created a Chaplin “silent movie,” wherein I would imitate Charlie live onstage, underscored with Tchaikovsky played by the brilliant and funny piano player Marc Shaiman. We wrote a scene where Gorbachev, looking to westernize his country, has a meeting with an American producer. With a makeup job complete with bad hair plugs, I played the slimy producer who brings the concept of creating a theme park called Lenin Land. We built a scale model of the Disneyland-like park, and a disbelieving Gorbachev watched a tiny roller coaster go right through dead Lenin’s head.

And speaking of Lenin, in a fantasy of who I might have been if history were different, I played a guard at Lenin’s Tomb who is a practical joker. One is not allowed to make a sound inside the tomb, but I use a hidden fart device to crack up the stoic soldier next to me, while I blame it on an American tourist. My favorite piece was a monologue where I played a man waiting on line, inspired by the thousands of stone-faced Russians I had seen standing on lines for goods. Many times, they didn’t know what the line was for; they’d merely joined it. My character is hoping for food, vodka, or raspberries that don’t have worms in them, all the while talking about what it’s like living there. It was a ballsy piece to do for the Russians, because it confronted them with the reality of their own lives. Finally I wrote a postconcert scene that has me leaving on the midnight train, and I bump into a young girl, who, in the magic of

Field of Dreams,

turns out to be my grandmother on her way to America. My sixteen-year-old daughter, Jenny, would play her own great-grandmother.