Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition (4 page)

Read Stretching Anatomy-2nd Edition Online

Authors: Arnold Nelson,Jouko Kokkonen

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Human Anatomy & Physiology

Execution

- Sit comfortably with the back straight.

- Place the right hand on the forehead.

- Pull the head back and toward the right so that the head points toward the shoulder.

- Repeat for the left side.

Muscles Stretched

- Most-stretched muscle:

Left sternocleidomastoid - Less-stretched muscles:

Left longissimus capitis, left semispinalis capitis, left splenius capitis

Stretch Notes

After the neck flexors become flexible, progress from stretching both sides of the neck simultaneously to stretching the left and right sides individually. Stretching one side at a time allows you to place a greater stretch on the muscles. This especially is important for those who stand hunched over with the head pointed mainly to one side.

When you stretch both sides of the neck simultaneously, the amount of stretch applied is limited by the stiffest muscles. Thus, the more flexible side may not receive a sufficient stretch. By stretching each side individually, you can concentrate more effort on the stiffer side.

You can perform this stretch while either sitting or standing upright. Although you can achieve a better stretch while sitting, choose whichever position feels best to you.

Chapter 2

Shoulders, Back, and Chest

There are five major pairs of movements at the shoulder: (1) flexion and extension, (2) abduction and adduction, (3) external and internal rotation, (4) retraction and protraction, and (5) elevation and depression. The bones of the shoulder joint consist of the humerus (upper-arm bone), scapula (shoulder blade), and clavicle (collarbone). The scapula and clavicle essentially float on top of the rib cage. Therefore, a major function of many upper-back and chest muscles is to attach the scapula in the upper back and the clavicle in the upper chest to the rib cage and spine. This provides a stable platform for arm and shoulder movements. Of the five movement pairs, retraction and protraction and elevation and depression usually are classified as stabilization actions.

Most of the muscles involved in moving and stabilizing the shoulder bones are located posteriorly. The scapula is a much larger bone than the clavicle and has room for more muscles to attach. The posterior (back) muscles (

figure 2.1

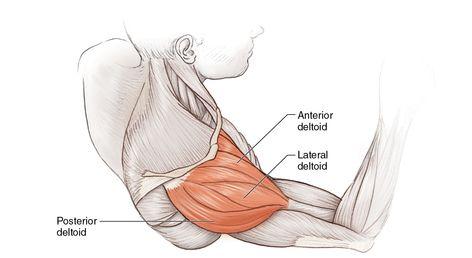

) are the infraspinatus, latissimus dorsi, levator scapulae, rhomboids, subscapularis, supraspinatus, teres major, teres minor, and trapezius (attached to the upper posterior rib cage, vertebrae, and scapula), as well as the deltoid (

figure 2.2

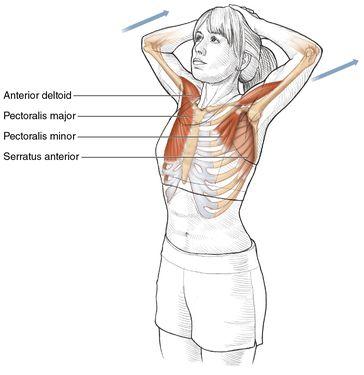

) and triceps brachii (attached to the scapula and humerus; see chapter 3). The anterior (front) muscles (

figure 2.3

) are the pectoralis major (attached to the clavicle, anterior rib cage, and humerus), pectoralis minor, subclavius, serratus anterior (attached to the anterior rib cage and anterior scapula), biceps brachii, coracobrachialis, and deltoid (attached to the anterior scapula and humerus).

Figure 2.1

Back muscles.

Figure 2.2

Deltoid muscle.

Figure 2.3

Chest muscles.

The shoulder, or glenohumeral, joint is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the head of the humerus and the glenoid fossa, a shallow scapular cavity that forms a socket for the humeral head. This joint is both the most freely moving joint of the body and the least stable. Upward movement of the humerus is prevented by the clavicle and the scapular acromion and coracoid processes, as well as by the glenohumeral ligaments and rotator cuff. Downward, forward, and backward humeral movements are limited by the humeral head’s position in the glenoid labrum, a circular band of fibrocartilage that passes around the rim of the glenoid fossa to increase its concavity. Along with the glenoid labrum, the humerus is held in place by several ligaments and muscle tendons that together form the rotator cuff.

The whole humerus head and the glenoid fossa are surrounded by the joint capsule, a collection of ligaments. Major ligaments include the anterior and posterior sternoclavicular, costoclavicular, and interclavicular ligaments, which help connect the clavicle to the rib cage. The coracohumeral, glenohumeral, coracoclavicular, acromioclavicular, and coracoacromial ligaments help interconnect the humerus, scapula, and clavicle bones. The major muscles and tendons providing rotator cuff stability are the infraspinatus, subscapularis, supraspinatus, and teres minor. Since these muscles attach more superiorly (atop the shoulder), most dislocations occur inferiorly (downward from the shoulder).

Since the shoulder muscles are a major component of shoulder stability, shoulder flexibility—the amount of possible movement in a particular direction—in all five movement pairs (e.g., extension and flexion) is greatly controlled by both the strength of the muscles and the extensibility of the antagonist muscles involved in the movement. Shoulder abduction, the range of motion away from the midline of the body, is limited by the flexibility of the ligaments in both the shoulder and the joint capsule and by the humerus hitting the acromion and the superior rim of the glenoid fossa (or shoulder impingement). Shoulder adduction, the range of motion toward the midline of the body, is additionally limited by the arm meeting the trunk. Shoulder flexion range of motion is limited by the tightness of both the coracohumeral ligament and the inferior portion of the joint capsule. Coracohumeral ligament flexibility influences shoulder extension range of motion along with shoulder impingement. Shoulder internal rotation is restricted by the flexibility of the capsular ligaments, while external rotation range of movement is limited by rigidity of the coracohumeral ligament and the tightness of the superior portion of the capsular ligaments. Additional factors for elevation include the tension of the costoclavicular ligament along with the joint capsule. For depression the other restrictors are the interclavicular and sternoclavicular ligaments. Finally, protraction is limited by tightness in both the anterior sternoclavicular and posterior costoclavicular ligaments, while retraction is limited by tightness in both the posterior sternoclavicular and anterior costoclavicular ligaments.

It is important to maintain proper balance between strength and flexibility in all shoulder muscles. Common complaints associated with the musculature of the shoulders, back, and chest are tight muscles and muscle spasms in the neck (middle and upper trapezius), shoulder (trapezius, deltoid, supraspinatus), and upper back (rhomboids and levator scapulae). Interestingly, the tightness felt in these muscles is usually a result of initial tightness in their antagonist muscles. In other words, tight muscles in the upper chest caused the tightness felt in the upper back. Tight chest muscles (e.g., the pectoralis major) cause a constant low-level stretch on the muscles of the upper back. Eventually, this low-level stretch elongates the ligaments and tendons associated with the upper-back muscles. Once these ligaments and tendons become elongated, the tone in their associated muscles falls dramatically. To reclaim the lost tone, the muscles must increase their force of contraction. Increased force in turn causes more stretch of the ligaments and tendons, and increased muscle contraction must compensate for that. Hence, a vicious cycle commences.

The best way to prevent or stop this cycle is to stretch the anterior shoulder and chest muscles. As the flexibility of these muscles increases, the tightness of the posterior muscles is reduced. Immediately after stretching, the strength of the muscles is diminished. It is a good idea to stretch the opposing muscles just before and immediately after working any group of muscles. If this is done three or more times a week, the muscles will actually increase in flexibility and gain strength. Stretching will also reduce the frequency of tightness for any group of muscles. Furthermore, shoulder impingement can occur with improper balance between shoulder muscle strength and flexibility. Since the gap between the humerus and scapular process is narrow, anything that further narrows this space, such as tight muscles, can result in impingement, leading to pain, weakness, and loss of movement.

Many of the instructions and illustrations in this chapter are given for the left side of the body. Similar but opposite procedures would be used for the right side of the body. Although the stretches in this chapter are excellent overall stretches, some people may need additional stretches. Remember to stretch specific muscles, and the stretch must involve one or more movements in the opposite direction of the desired muscle’s movements. For example, if you want to stretch the serratus anterior, perform a movement that involves shoulder depression, shoulder retraction, and shoulder adduction. When any muscle has a high level of stiffness, you should use very few simultaneous opposite movements. For example, to stretch a very tight pectoralis major, start by doing shoulder extension and external rotation. As a muscle becomes loose, you can incorporate more simultaneous opposite movements.

Beginner Shoulder Flexor Stretch

Execution

- Stand upright and interlock your fingers.

- Place your hands on top of your head.

- Contract your back muscles, and pull your elbows back toward each other.

Muscles Stretched

- Most-stretched muscles:

Pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, anterior deltoid - Less-stretched muscle:

Serratus anterior

Stretch Notes

Poor posture is the primary reason for tight shoulder flexor muscles. Poor posture is commonly seen when the person hunches forward or works with his arms extended out in front. Tightness usually is accompanied by tight neck extensors. Having both groups of muscles tight increases the chances of developing a vulture neck and contributes to breathing problems. Injuries, either acute or overuse, that lead to shoulder impingement, shoulder bursitis, rotator cuff tendinitis, or frozen shoulder can also lead to tight shoulder flexors.