Television's Marquee Moon (33 1/3) (15 page)

Read Television's Marquee Moon (33 1/3) Online

Authors: Bryan Waterman

The shows at Mother’s in October ’75 featured Television in its mature incarnation, having weathered a close call with another personnel change that may have proven disastrous, given the band’s increasing reliance on the interplay between its two guitarists as one of its defining elements. Set lists now included a new song, the funereal, Oriental-chainsawed “Torn Curtain,” which would appear on

Marquee Moon

. “Marquee Moon,” now an audience favorite, was clocking in at over eight minutes, the dueling guitar solos now sounding like the braided bolts of lightning referenced in the lyrics. (The song’s climax and dénouement, though, remained to be evened out.) Wolcott, writing in early 1977, recalled one of the Mother’s shows as the moment Television’s “image came in crisp and clear.” He shared a table with Richard Robinson, Lou Reed, and Reed’s current flame, a Club 82 drag queen named Rachel:

[T]hroughout the evening Lou grumbled and bitched about everything and nothing, like a sailor with a sore case of the clap. When Television did its version of Dylan’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door,” Lou finally made a grouchy exit, but some loose voltage of rancor hung in the air, and when TV concluded with its anthem “Kingdom Come,” the song surged with angry force. Towards the end of the song, Verlaine broke a string, then methodically broke every string, snapping them with stern malicious delight; he then laid his guitar down, and went to his amplifier and began slamming it against the wall, slamming it hard and obsessively, with the manic cool of Steve McQueen assaulting a pillbox in “Hell Is For Heroes.” The band kept playing, Verlaine kept pummeling the amplifier, and, finally, Verlaine abandoned the battered amplifier and sauntered off stage and the kingdom come was spent.

233

This wasn’t the first time Verlaine had engaged in this sort of assault on his equipment. Back in July, Richard Mortifoglio had described a very similar act of “strangely quiet violence,” shortly following Hell’s departure from the band, when Verlaine “ripped all the strings off his guitar and them methodically knocked his amp around a bit.” Instead of nodding to McQueen’s portrait of a soldier on a suicide mission, Wolcott should have recognized Verlaine’s act as an echo of Jeff Beck’s assault on an amplifier in Michaelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film

Blow-Up

, itself modeled on Pete Townshend’s infamous guitar-smashing antics. In the film, pieces of Beck’s guitar pass from the stage into the audience like a sacrament, starting a riot while the Yardbirds chug through “Stroll On.” In Verlaine’s case, too, smashing equipment seemed liturgical, a ritual by which he let band members go or took them back, in either case for the sake of the music. He was, you could say, just trying to tell a vision.

168

Heylin (1993: p. 121). Fliers for the Truck and Warehouse show feature a photo with Lloyd in the middle.

169

Dove (1974).

170

Swirsky (2003).

171

Heylin (2007: p. 26).

172

“Television” (1975).

173

“Tom Verlaine” (1995).

174

Fields (1996: p. 23 [16 January 1975]).

175

Betrock (1975b).

176

Jones (1977).

177

Charlesworth (1976).

178

Hoffmann, Mumps History; Fields,

SoHo Weekly News

, 7 Nov. 1974.

179

Betrock (1975c).

180

Betrock (1975c).

181

Kozak (1988: p. 39). Despite Kaye’s recollection, Smith signed her contract with Arista only a few days into the spring residency.

182

Fields (1996: pp. 24–5 [27 March 1975]).

183

Rockwell (1975b).

184

Fields (1996: p. 25 [10 April 1975]).

185

Rockwell (1975a).

186

Kozak (1988).

187

McNeil and McCain (1996: p. 172).

188

Betrock (1975b).

189

Fields,

SoHo Weekly News

, 10 April 1975.

190

Fields,

SoHo Weekly News

, 17 April 1975.

191

Heylin (1993: p. 138).

192

Mitchell (2006: p. 58).

193

Richard Hell Papers, Box 9, Folder 594.

194

McNeil and McCain (1996: p. 196).

195

Heylin (1993: p. 160).

196

See esp. Heylin (1993: pp. 160–1).

197

Bockris and Bayley (1999: p. 112).

198

Goldman (1977).

199

Kent (1973a).

200

Kent (1977b).

201

Kent (1977b).

202

Kendall (1977).

203

Gendron (2002: pp. 252–4).

204

See, for example, Bangs (1980: p. 17); Harry, et al. (1998 [1982], p. 18).

205

Heylin (1993: p. 139).

206

Betrock (1975a).

207

Baker (1975).

208

Murray (1975a).

209

Murray (1975a).

210

Fields (1996: p. 26 [12 June 1975]).

211

Heylin (1993: p. 182).

212

Mortifoglio (1975).

213

Photographer Maureen Nelly, in Heylin (1993: p. 237).

214

Bockris and Bayley (1999: p. 122).

215

Shelton (1986: p. 447); Leichtling (1975). During the ’70s Richards omitted the “s” from his surname.

216

Chrome (2010: p. 127).

217

Fields (1996: p. 27 [24 July 1975]).

218

Kozak (1988: p. 42).

219

Wolcott (1975a).

220

Wolcott (1975a).

221

Wolcott (1975a).

222

Wolcott (1975a).

223

Elliott (1977).

224

Mitchell (2006: ch. 12).

225

Hell (1996: p. 50).

226

Hell (2001: p. 41).

227

Verlaine (1976).

228

Marcus (2005: p. 3).

229

Licht (2003).

230

Wolcott (1975b).

231

Laughner (1976).

232

Heylin (2007: p. 75).

233

Wolcott (1977).

The [CBGB’s] bands weren’t really alike. There was a self-awareness to their work that spoke of some knowledge of conceptual art — these weren’t cultural babes-in-the-woods, despite Johnny’s and Joey’s and Dee Dee’s and Tommy’s matching leather jackets. Tom Verlaine once said that each grouping was like a separate idea, inhabiting their own world and reference points. Of them all, I loved watching Television grow the best.

— Lenny Kaye, intro to

Blank Generation Revisited,

(1996)

Patti Smith’s

Horses

appeared in November to general acclaim and brisk early sales. Lester Bangs, in a rave review for

Creem

, declared she was backed by “the finest garage band sound yet in the Seventies” and discerned in her songs a heady mix of “the Shangri-Las and other Sixties girl groups, as well as Jim Morrison, Lotte Lenya, Anisette of Savage Rose, Velvet Underground, beatniks, and Arabs.”

234

The

New York Times Magazine

profiled her in December, though the piece had nothing on the rest of the downtown scene and instead featured a photograph of her with Dylan. At the end of December her band played three nights at the Bottom Line for a star-studded audience that included Hollywood actors, most of CBGB’s major players, rising rock luminaries such as Springsteen and Peter Wolf (with his wife, Faye Dunaway), and the rock critical establishment, including Jann Wenner,

Rolling Stone

’s editor, who had been slow to come around to the new New York sound. Television joined Smith’s band on stage at least one night, as did John Cale. “[S]imply, it was a wonderful weekend,” wrote Danny Fields, “and it bodes well for everyone involved.”

235

As 1976 began, Television seemed ready to fulfill that promise. The sound that would make

Marquee Moon

was more or less in place. Once they began performing new compositions “See No Evil” and “Guiding Light” in late ’75, all the songs were written that would eventually be on the album. Their live shows attracted larger crowds than ever: at CBGB’s they broke house records two nights in a row in December before headlining the final show of CB’s Christmas Rock Festival on New Year’s Eve. Smith joined them on stage at CBGB’s around 5 am to help them finish their second set. Fields, who named Television and the Ramones the “Cosmic Newcomers” in his year-in-review column, reported that Lou Reed had been won over as a fan, that the underground film director John Waters had been to see them, and that Paul Simon had come to a show in November with Arista’s Clive Davis.

236

But still no contract, a situation that would wear thin Television’s relations to other CB’s bands over the coming months, as Verlaine came to feel more and more distant from the scene he had helped start. Some of their peers — starting with the Ramones — had negotiated contracts of their own. He would feel even more separated from the musicians overseas who would form the UK punk scene, many of them fueled by legends of New York’s Bowery enclave.

When the

NME

sent Murray back to New York near year’s end to find “The Sound of ’75,” he somehow missed Television’s live shows. He did hear the single, though, which couldn’t live up to his memory of seeing the band live the previous spring, and so he only offered the band a mixed review in his feature, which was the most extensive the scene had received overseas. Noting the band’s “wilful inconsistency,” he concedes: “And since they still haven’t recorded anything impressive (viz the debacle of the Eno Tape, a tale of almost legendary status in CBGB annals), it seems unlikely that any of the major labels who’ve decided that they can get along without Television are likely to change their minds unless a particularly hip A&R man manages to catch Tom Verlaine and his henchmen on a flamingly good night.”

237

That a reporter from the

NME

was talking about having heard the “legendary” Eno tapes seriously unsettled Verlaine. It’s not quite clear when Verlaine first heard Roxy Music’s new album

Siren

, but by the end of ’76 he was telling reporters he believed Richard Williams or Brian Eno had distributed their demo tape so promiscuously that Ferry had ripped off at least a dozen lines. Roxy’s song “Whirlwind,” for instance, included the line “This case is closed,” Verlaine’s sign-off in “Prove It.” But Verlaine’s list of resemblances seems superficial. The lack of a contract seemed to be pushing him toward paranoia. As early as December ’75, Danny Fields had noted Lou Reed’s habit of taping CBGB’s shows on a portable Sony cassette recorder, still a novelty.

238

But when Reed packed his recorder into a Television show in the summer of ’76, Verlaine bristled. Lisa Robinson took notes on the confrontation, which came on the cusp of Television’s finally signing with Elektra:

“What’s he doing with that tape recorder?” mumbled Tom Verlaine. “Do you think I should ask him to keep it in the back?” Ask him for the cassette, I suggested, or the batteries. “Hey, buddy,” Verlaine said to Reed. “Watcha doin’ with that machine?” Lou looked up, surprised. “The batteries are run-down,” he said. “Oh yeah?” responded Verlaine. “Then you won’t mind if I take it and hold it in the back, will ya?” Lou handed a cassette over, then said, “You’d make a lousy detective, man. You didn’t even notice the two extra cassettes in my pocket, heh-heh.” Verlaine was not amused. “O.K. then, pal, let me have the machine. I’ll keep it in the back for you.” Reed handed over the machine, then said, “Can you believe him?” His eyes widened in surprise.

239

Verlaine’s paranoia may have been warranted: when Reed played the Palladium at the end of ’76 in support of his

Rock and Roll Heart

LP, he played in front of a bank of Television sets, as if to stage a pissing contest with the new underground.

As 1976 began critics still grappled with how to label the music on the downtown scene. A profile piece by Lisa Robinson in

Creem

called the CB’s bands the “new Velvet Underground.” John Rockwell, in the

Times

, continued to use the label “underground rock,” and in January he placed Television at the top of the “pecking order [that] has emerged on the feverishly active New York” scene. Talking Heads, whom he personally found more “gripping” than Television, followed close behind.

240

The search for a label flexible enough to accommodate the broad-ranging CB’s scene ended in the first weeks of the year, when fliers popped up around the neighborhood announcing that “PUNK Is Coming.” They heralded the arrival of a new magazine, whose first issue appeared in January, obviously influenced by

MAD

, hand-lettered and with a Frankensteinish Lou Reed on the cover. The image simultaneously suggested Reed’s repeated return from the dead and also the way the new scene had been stitched together from ingredients including large chunks of the Velvets’ corpse. “DEATH TO DISCO SHIT!” thundered John Holmstrom’s first editorial headline. In

Punk

’s second issue, a supposedly drunken Verlaine dispenses a dissertation on the French poet Gérard de Nerval (he preferred Nerval to Paul Verlaine), and Richard Lloyd suggests that “you can’t admire life unless you admire death.”

Punk

asks Television’s guitarists about their historic stint at CBGB’s with Patti. “We were playing there a year and a half before we did that,” says Verlaine, a tad defensively. Lloyd chimes in: “Two years.” Verlaine: “But nobody knows that. At least two years.” Lloyd mistakenly asserts it was April or May of ’72, and Tom offers a version of the origin myth in which he and Lloyd discover the bar. When

Punk

asks about Theresa Stern’s

Wanna Go Out?

, Tom answers: “Teresa’s in the hospital. Yeah. She had a breakdown … in Hoboken. She was turnin’ on some John and she — she just — her mind just snapped. I don’t think she writes no more. She’s the Syd Barrett of the poetic scene.”

241

Over time it would become clear that

Punk

’s editors preferred the straight-forward pummeling of the Ramones or the raw intensity of Richard Hell’s bands to Television’s more cerebral anthems: “party punk” over “arty punk,” in terms Wolcott would later use.

242

In February yet another new magazine appeared on the scene:

New York Rocker

, edited by

SoHo Weekly News

’s Alan Betrock, with staff writers including Debbie Harry, Roberta Bayley, and Theresa Stern (now a solo pseudonym for Hell), who offers a humorous review of a Heartbreakers show. Like

Rock Scene

,

New York Rocker

helped create the sense that local culture heroes were already stars — “before they’d even crossed the Hudson,” as the magazine’s second editor, Andy Schwartz, recalls.

243

Much more than

Punk

did,

New York Rocker

lavished attention on Television (fig. 5.1). The debut issue featured Verlaine on the cover and, in its centerfold, included an extensive autobiographical sketch, in which he described his childhood music experiences on piano and sax, his twin brother (“I believe that stuff about twins having this ethereal connection between each other”), his high school friendship with Hell and their experience running away, his introduction to Genet and Kerouac. The extensive space devoted to this narrative makes plain Verlaine’s star status on the scene: he is also perceived to be the band’s organizing force. When he reaches the point of his arrival in New York, he says he hung around Hell “but then I didn’t see him too much; he was running around his [poetry] circle an’ I was working at the Strand Bookstore; same place as Patti.” The bookstore gave him opportunities to read and take drugs and opened him to the realization that “people are really doing things. It’s not just words; it’s a real event that’s happening, so to speak.” To some extent, Verlaine’s entire narrative is about the need for something to happen: “I’m not disappointed that we haven’t signed,” he wrote, “but it’s about time now. I mean you have to decide if it’s going to be a career or a hobby, and if it’s going to be a career, you have to sign.”

244

Betrock positioned his publication in territory adjacent to

Punk

and

Rock Scene

. Like

Rock Scene

, Betrock modeled his approach on fan-mags like

16

. If the Robinsons featured photos of David Byrne shopping for groceries, Betrock ran weekly write-in popularity polls. (Television captured the spot of #1 band in the inaugural issue.) An article on “NY Rock Dress Sense” in the magazine’s second issue glossed Television’s post-Hell look: “Tom Verlaine cheek bones, and Tom Verlaine eyes. Get them at your nearest hobby and toy store. Clothes — nothing more than functional.” If Betrock aimed to consolidate the scene’s energies by representing local musicians as already having achieved star status, some tension exists with Verlaine’s growing desire to keep himself from being pinned with a New York label: “I mean, NY’s a great town,” Verlaine wrote. “Coltrane, Dylan, The Blues Project — but now all they think of is glamour. … [T]oo many of them seem overly fixated on someone else — you know the Beatles, Lou Reed, or the Dolls.”

245

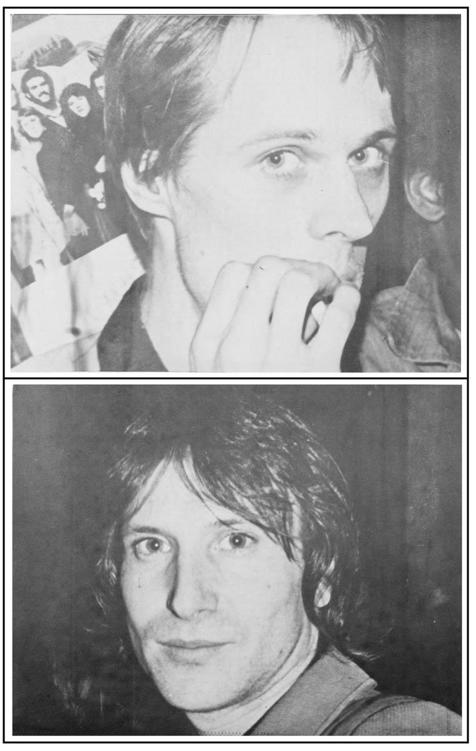

FIGURE 5.1

New York Rocker

#3, May 1976, centerfold pin-up. Photo by Guillemette Barbet. Clockwise from top left: Verlaine, Lloyd, Ficca, Smith. Courtesy Andy Schwartz/

New York Rocker