The 30 Day MBA (42 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

But that still begs the question of what constitutes âgood'. The FTSE4Good Index sets out to measure the performance of companies that meet globally recognized corporate responsibility standards. For inclusion a company must be:

- working towards environmental sustainability;

- developing positive relationships with stakeholders;

- upholding and supporting universal human rights;

- ensuring good supply chain labour standards;

- countering bribery.

It also excludes companies that have been identified as having business interests in these industries:

- tobacco producers;

- companies manufacturing either whole, strategic parts, or platforms for nuclear weapon systems;

- companies manufacturing whole weapons systems;

- owners or operators of nuclear power stations;

- companies involved in the extraction or processing of uranium.

This only serves to highlight the problem of deciding what is ethical and what is not. For example, is mining uranium for nuclear power really more harmful than, say, switching to biofuels which, aside from probably releasing between two and nine times more carbon gases over the next 30 years than fossil fuels, will almost certainly cause food prices to stay high, particularly in the developing world? Or is the motor industry, whose products kill more people every year than the armaments industry, a more ethical and socially responsible sector?

However, a small but growing band of business schools believe that there is enough mileage in social responsibility and ethics to launch âgreen' MBA programmes that emphasize a triple bottom line, also known as âTBL' or â3BL' â profit, people, planet. Antioch University (

www.antiochne.edu/om/mba

), New England, Dominican University (

www.greenmba.com

), California and Duquesne University (

http://mba.sustainability.duq.edu

) in Pittsburgh are among those offering such programmes.

- Outsourcing

- Production methods

- Controlling operations

- Maintaining quality

- Information systems

M

IT Sloane defines operations management as the subject that âdeals with the design and management of products, processes, services and supply chains. It considers the acquisition, development, and utilization of resources that firms need to deliver the goods and services their clients want'. This, the school goes on to explain, ranges from strategic issues such as where plants are located down to tactical levels such as plant layout, production scheduling, inventory management, quality control and inspection, traffic and materials handling, and equipment maintenance policies.

To stay ahead, companies need to generate innovation, organize production, collaborate with other companies and manage the performance of activities, processes, resources and control systems used to deliver goods and services. Operations management is the catch-all title used to hold all these disparate fields together. Often in business schools the subject is afforded a distinct syllabus of its own, as for example is the case at Cranfield School of Management, Warwick and Bocconi, in Milan, Italy. At Cardiff Business School, Logistics and Operations Management are bundled together with a strong emphasis on âLean Thinking' and in Barcelona's Esade Business School âInnovation' is the partner subject.

However the subject is taught, the foundations if not the content started out with the work of Frederick W Taylor. Usually referred to as the âfather of scientific management', he studied and measured the way people worked, searching out ways to improve productivity. His book,

The Principles of Scientific Management

(1911, Harper and Row, New York), showed how

science could replace apprenticeship as the way to transfer knowledge about how tasks should be done. Though much misunderstood and misapplied â the Soviet Union adopted his methods as the foundation for its five-year plans â Taylorism, as his work became known, was the spur to the many variants and extensions that are today bundled under operations management.

The next big boost to the discipline took place with the introduction of mathematical models used during the Second World War to make maximum use of scarce resources. Fairly mundane tasks, such as removing bottlenecks in tank production, led to dramatic increases in output. More esoterically, operations research, as this branch of the subject became known, was used to work out the optimum size of convoy to evade destruction by German U-boats as well as the depth at which explosives would be most effective against the submarines themselves.

MBAs, unless they have a strong background in mathematics, are unlikely to be able to apply any of the techniques and tools described below without expert help. But they do need to be aware that such methods are on hand and so can recommend their application when the opportunity or relevant problem arises.

Outsourcing and the value chain

The classic opening question in any business analysis that MBAs will find themselves addressing with increasing frequency is: what business are we in? Later in that analysis will come a more fundamental and challenging question: what business should we be in? These are strategic boundary questions that will be explored in more detail in

Chapter 12

, Strategy. The answers are also key to deciding what operations a business should and should not undertake itself, and the answer will not always be the same, as business competence and market opportunities change.

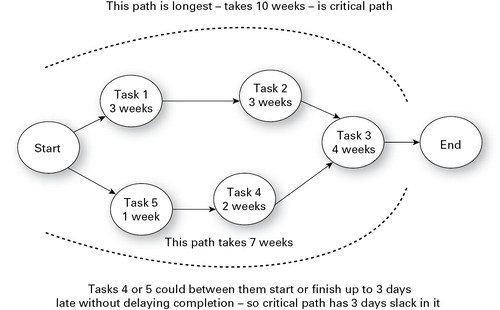

The business example shown in

Figure 10.1

doesn't have to do all the activities, from creative design, through manufacture, to selling out from its own retail outlets. It is highly likely that there are other businesses better at certain elements of the process. For example, most businesses don't retail the products they manufacture, and even within the same industry different approaches are taken. Dell only sells direct via the internet, Apple sells via the internet, through a small number of company-owned outlets and through other retailers. IBM, having virtually created the personal computer industry

in 1981, sold its PC division to the Chinese company Lenovo on 1 May 2005 for $655 million in cash and $600 million in Lenovo stock, moving away from personal consumers to concentrate on businesses.

FIGURE 10.1

Â

Maternity clothes value chain

Outsourcing is the activity of contracting out the elements that are not considered core or central to the business. There are obvious advantages to outsourcing: the best people can do what they are best at. But the approach can get out of hand, if left unmanaged. In 2008, IBM completed a major overhaul of its value chain and for the first time in its century-long history created an integrated supply chain (ISC) â a centralized worldwide approach to deciding what to do itself, what to buy in and where to buy in from. Suppliers were halved from 66,000 to 33,000; support locations from 300 to 3 global centres, in Bangalore, Budapest and Shanghai. Manufacturing sites reduced from 15 to 9, all âglobally enabled' in that they can make almost any of IBM's products at each plant and deliver them anywhere in the world. In the process IBM has lowered operating costs by more than $4 billion a year.

Quality control is one strategic issue when it comes to outsourcing, and an emerging danger with the arrival of the âsocially minded customer' is that people are looking more closely at companies and their products before buying from them. Getting garments made cheaply by child labour is very much an issue on consumers' radar. So while outsourcing plays a vital role in operations, it still has to be managed and to conform with corporate ethical standards.

Production methods and control

Manufacturing has come a long way since Adam Smith's observation in his book,

An Inquiry into the Nature And Causes of the Wealth of Nations

(1776), that:

The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is anywhere directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labourâ¦. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day. There are in a pound upwards of four thousand pins of a middling size. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty.

By Smith's calculations, organizing production efficiently increased output by 2,400 times, leaving the market itself as the primary limiting factor. Since

then the hunt has been on for ever more efficiencies in the methods of production. The main production methods employed today are:

- One-off production is when a single product is made to the individual needs of a customer, for example a designer dress. This is very much the pre-Smith way in which everything was made, often without the use of any machinery.

- Batch production involves the making of a number of identical products at the same time, then moving on to make a different product later. For example, a small food processing factory could make sausage rolls in the morning and pizzas in the afternoon. This approach requires some basic machinery and Smith would probably recognize this process were he alive today.

- Mass production is used for larger-scale production using machinery, often many different machines, for much of the work where individual tasks are carried out repetitively. This is an efficient and low-cost method of production for small and medium-sized businesses.

- Continuous-flow production produces the high volumes required by larger companies. These are highly automated and their cost usually requires them to be run 24/7. By reducing the workforce needed this eliminates one of the blockages that Smith saw: âthe improvement of the dexterity of the workman necessarily increases the quantity of the work he can perform'.

- Computer-aided manufacture (CAM) is a continuous-flow production method controlled by computers, such as used in the motor industry.

- Lean manufacturing is an approach ascribed to Toyota, where they sought to eliminate or continuously reduce waste â that is, anything that doesn't add value. Waste in the production process taking the âlean' approach is categorized under such headings as:

- Transport: Keep process close to each other to minimize movement.

- Inventory: Carrying high inventory levels costs money and, if too low, orders can be lost. âJust in time' (JIT) manufacturing should be aimed for.

- Motion: Improve workplace ergonomics so as to maximize labour productivity.

- Waiting: Aim for a smooth, even flow so that staff and machines are working optimally, reducing downtime to a minimum.

- Defects: Aim for zero defects as that directly reduces the amount of waste.

- Transport: Keep process close to each other to minimize movement.

Production scheduling

Production scheduling is the process used to get the optimum amount of output at the lowest cost. Its success is measured by being able to meet delivery promises while hitting profit margin objectives. It achieves this by identifying possible resource conflicts; directing sufficient labour and machinery to tasks on time; accommodating downtime and preventative maintenance schedules; and minimizing stock and work in progress levels. A production schedule also gives the production team explicit targets so that supervisors and managers can measure their performance.

The techniques used to facilitate scheduling which an MBA should understand include the following.

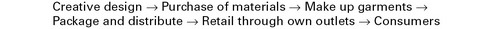

Gantt Charts

Henry Gantt, a mechanical engineer, management consultant and associate of Frederick Taylor, showed how an entire process could be described in terms of both tasks and the time required to carry them out. He developed what became known as the Gantt chart, to help with major infrastructure projects, including the Hoover Dam and US Interstate highway system, around 1910. By laying out the information on a grid with tasks on one axis and their time sequence along the other it was possible to see at a glance an entire production plan as well as highlight potential bottlenecks. Gantt charts can be used for any task, not just production scheduling, as

Figure 10.2

, giving an example of how a website design project could be planned, demonstrates.

FIGURE 10.2

Â

Gantt chart showing weekly tasks for a website design project

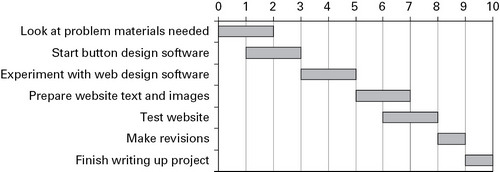

Critical path method (CPM)

A more sophisticated way to schedule operations was developed in the late 1950s. DuPont, the US chemical company, first used CPM to help with shutting down plants for maintenance. Later, the US Navy adapted it and improved it for use on the Polaris project. CPM uses a chart (see

Figure 10.3

) showing all the tasks to be carried out to complete a scheduled activity, the sequence in which they have to be carried out and how long each event, as tasks are known, will take to be completed. The critical path is the route through the network that will take the longest amount of time. The significance of the critical path is that any delays in carrying out events on this path will delay the whole project. Tasks not on the critical path have more leeway, and may be slipped without affecting the end date of the project. This is called slack or float.

FIGURE 10.3

Â

Critical path method applied